Created by Grace O'Mara and Savita Maharaj

Why Do We Encode Literary Texts?

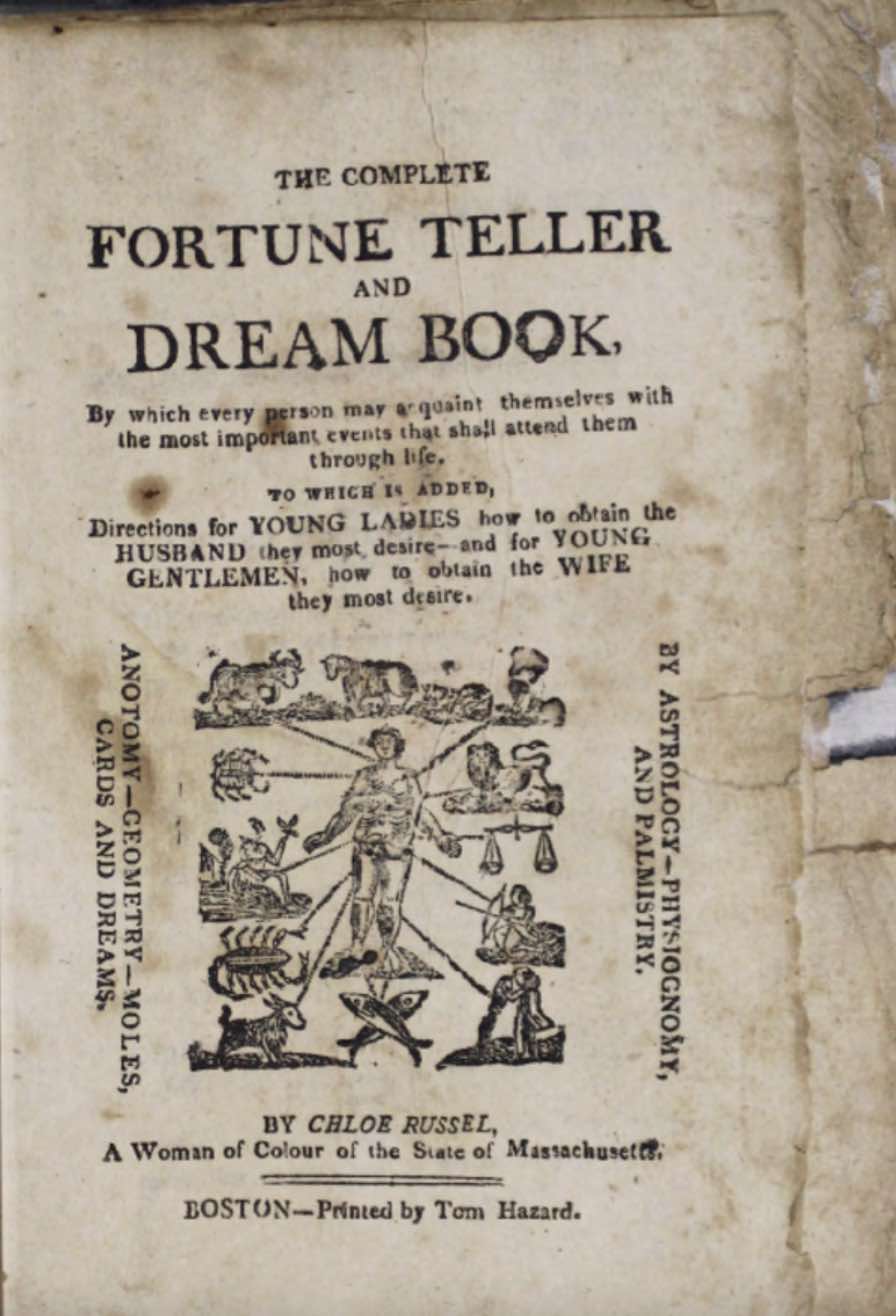

Encoding a text entails converting the content of a text such as The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book into code so that it can be understood in a digital format. Literary texts are not only encoded as a way of sharing them with a larger audience, but also causes one to break down the text in an intimate and detailed way. This exhibit will explore how one can do digital humanities research in the context of Chloe Russel’s The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

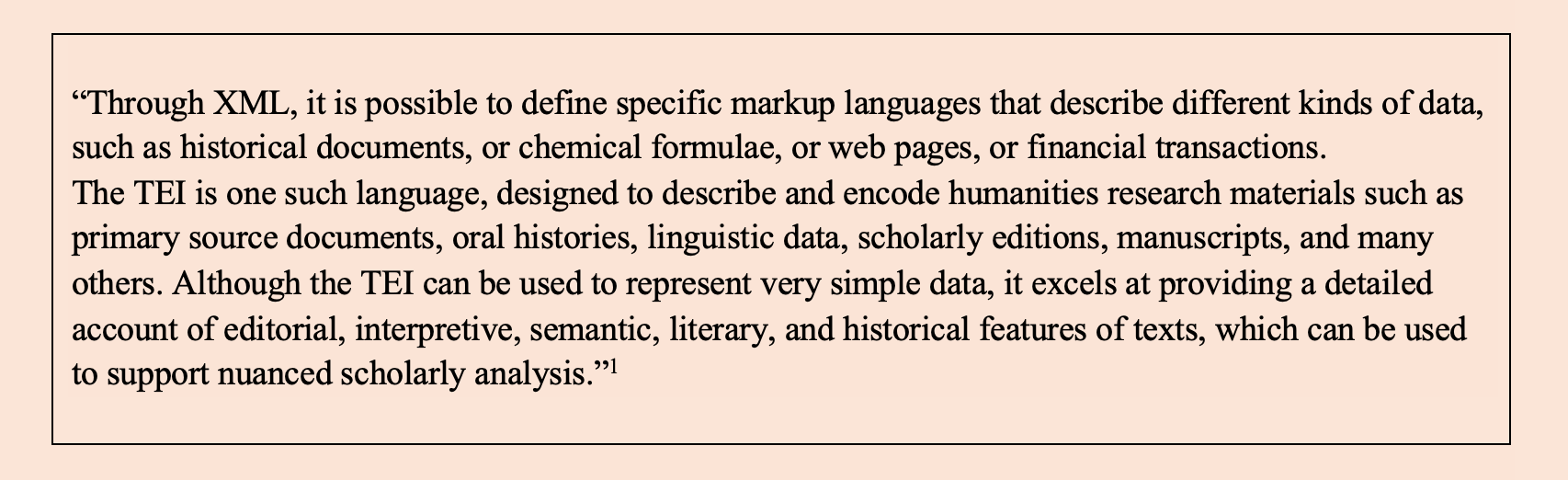

Two major components of encoding are XML and TEI. XML is how we present the text while TEI is the specific words and elements used to code for a specific property. Sarah Connell describes the difference between XML and TEI in the article Learning from the Past: The Women Writers Project and Thirty Years of Humanities Text Encoding writing:

Breaking Down the Code

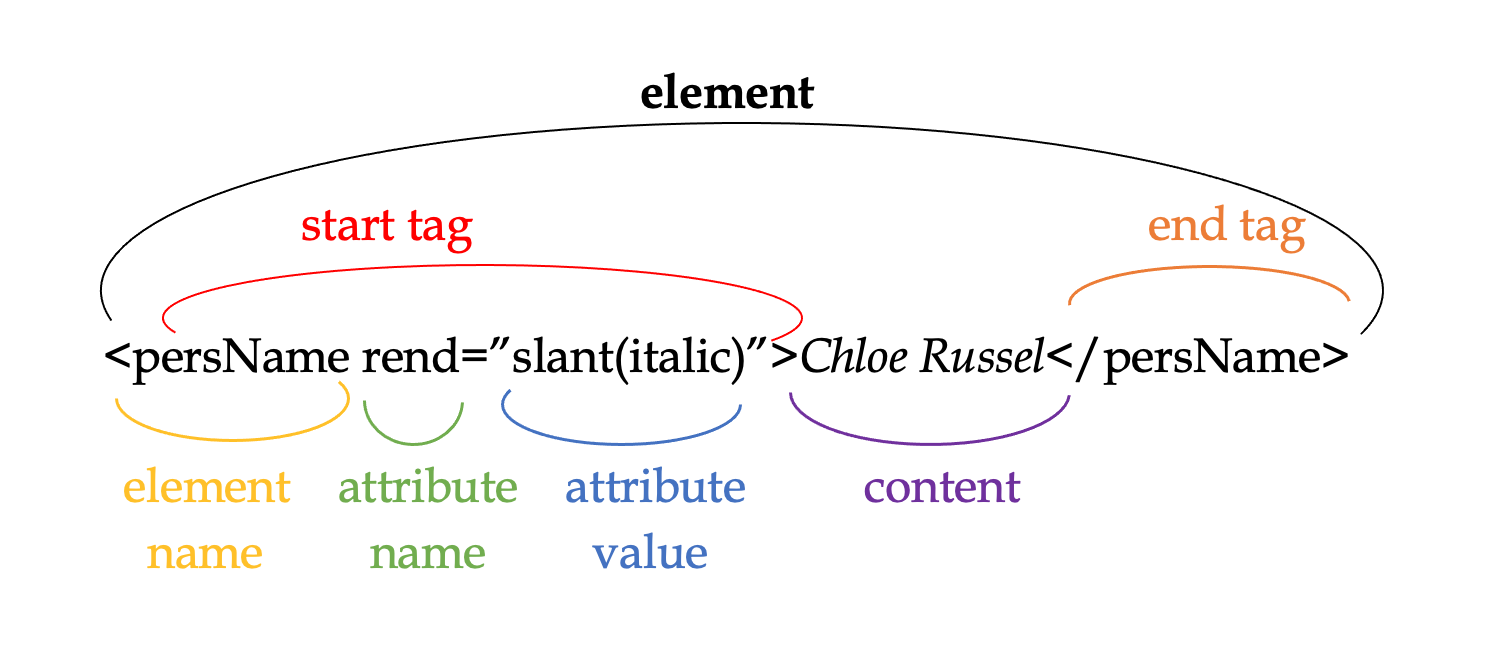

An element is used when the encoder wants to draw attention to an area of the text A start and end tag for each element is required because without one or the other the code would be ill-formed and the computer program would not be able to read what has been typed. Angle brackets are needed to indicate that persName is not just another word in the text but is in fact an element stating that “Chloe Russel” is a person’s name. Attributes are like adjectives that are used to signify when the content needs to be recognized.

Encoding Decisions

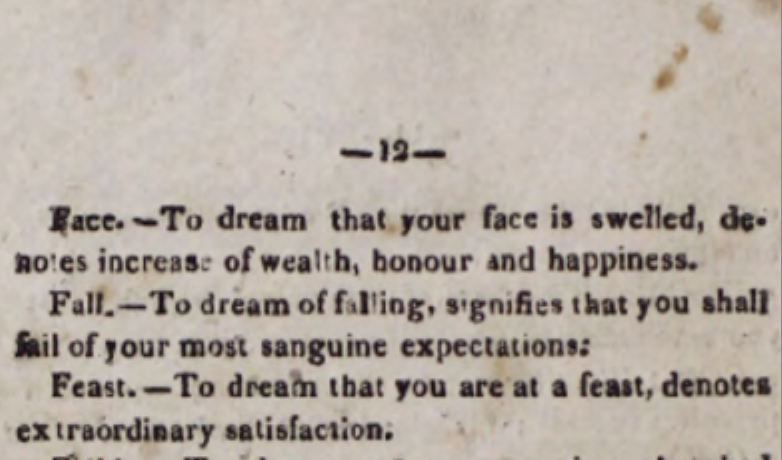

There are multiple levels of complexity one can apply to their encoding and these additions vary based on what you want to focus on. We will look at a page from The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book as an example.

The words are surrounded by an <ab> (also known as “anonymous block”) – often used for a section of text that is not specific enough to be labeled a paragraph. Another element used to mark the structural components of this page is <lb/> which stands for line break. Although this might seem like a minor component, it is important because without it, one would not know when words start on a new line. Other nouns that are noted include the author’s name (<persName>) and place names (<placeName>) such as Massachusetts. While this markup points out some of the main structural features of this page it leaves much to be desired. Below I include a more detailed encoding of the text.

One of the main differences between this photographed encoding and the more basic edition is the inclusion and specificity of the text’s rendition. Here the rend attribute is added and given specific values to express how the text can be seen. First, rend="align(center)" is added to <ab> to show that all of the text on this page is centered. To indicate that the author’s name is in all capital letters rend="case(allcaps)" has been added to <persName>. In this version, the most important visual aspect that has been noted is the illustration of the author. The elements <figure> and <figDesc> were added to express that all of the text below the image is used to describe/explain the drawing while <figDesc> is a chance for the encoder to explain what the illustration looks like as readers of the encoded version will not be able to see it for themselves. The element <ab> was also given a type="caption" to further express that the purpose of the text below the portrait is to describe the illustration. To signify that this page represents a significant division of the text <div> was added with a type="frontispiece" which is used to signify an image (often of the author) that exists at the front of a work. The last element that was added to this version of the encoding is <name> which was placed around the terms “Old Witch” and “Black Interpreter”. The <name> element is used to mark proper nouns, among other things, and the encoder of this text decided that “Old Witch” and “Black Interpreter” fit this description.

Even after adding all of these tags, there are still many features unmarked such as the handwritten numbers on the top left of the page, the size difference in letters, the gender of the author, and an extremely detailed description of the pictured. It is also important to remember that the decisions an encoder makes do not always represent all the encoding possibilities.

The Benefits of Encoding

There is no one way to encode a text. Depending on the goal or intention of a project different elements may be tagged or ignored; Russell’s work could be encoded multiple ways depending on what the encoder is trying to achieve with their markup. Cummings notes that although one encoded document may not represent all of the ways it could be read, “it is precisely the potential of a digital edition to be near-infinitely refactorable and dynamically to provide different views depending on external interactions.”2I got to take part in the encoding of The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book where I was able to proof this document. This essentially means I went through this text line by line and compared the book with code written by the previous encoder. While this process involves a little less engagement than encoding this document from scratch, proofing requires paying close attention to both the work and the markup in order to spot any errors or possible alterations that could be made.

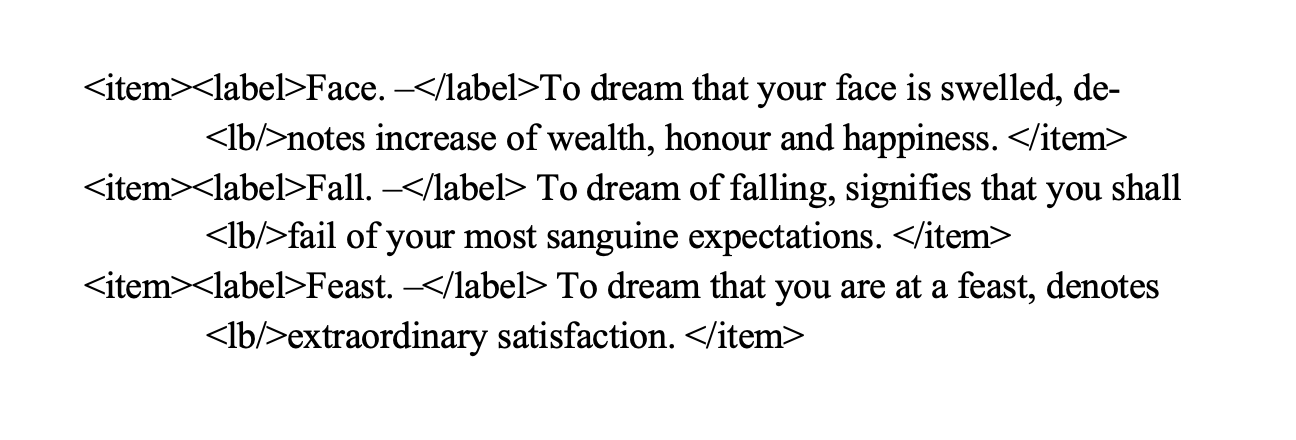

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum, Book, 12.

Above, there is an image of Russel’s work; under the description of “Nuts”, the word “trifling” is split across two lines. Words existing across two lines are quite common but notice that the hyphen connecting the two parts is absent. I proposed that we utilize the elements <choice>, <sic>, and <corr> so that Oxygen would read it as one word rather than two distinct words. The markup was than changed from tri <lb/>fling to <choice><sic>tri <lb/>fling</sic><corr>tri-<lb/>fling</corr></choice> to indicate that the WWP made a conscious decision to add the hyphen despite it not existing in the original copy of the work. This example shows how sometimes those encoding a document make choices to add and remove aspects of the text.

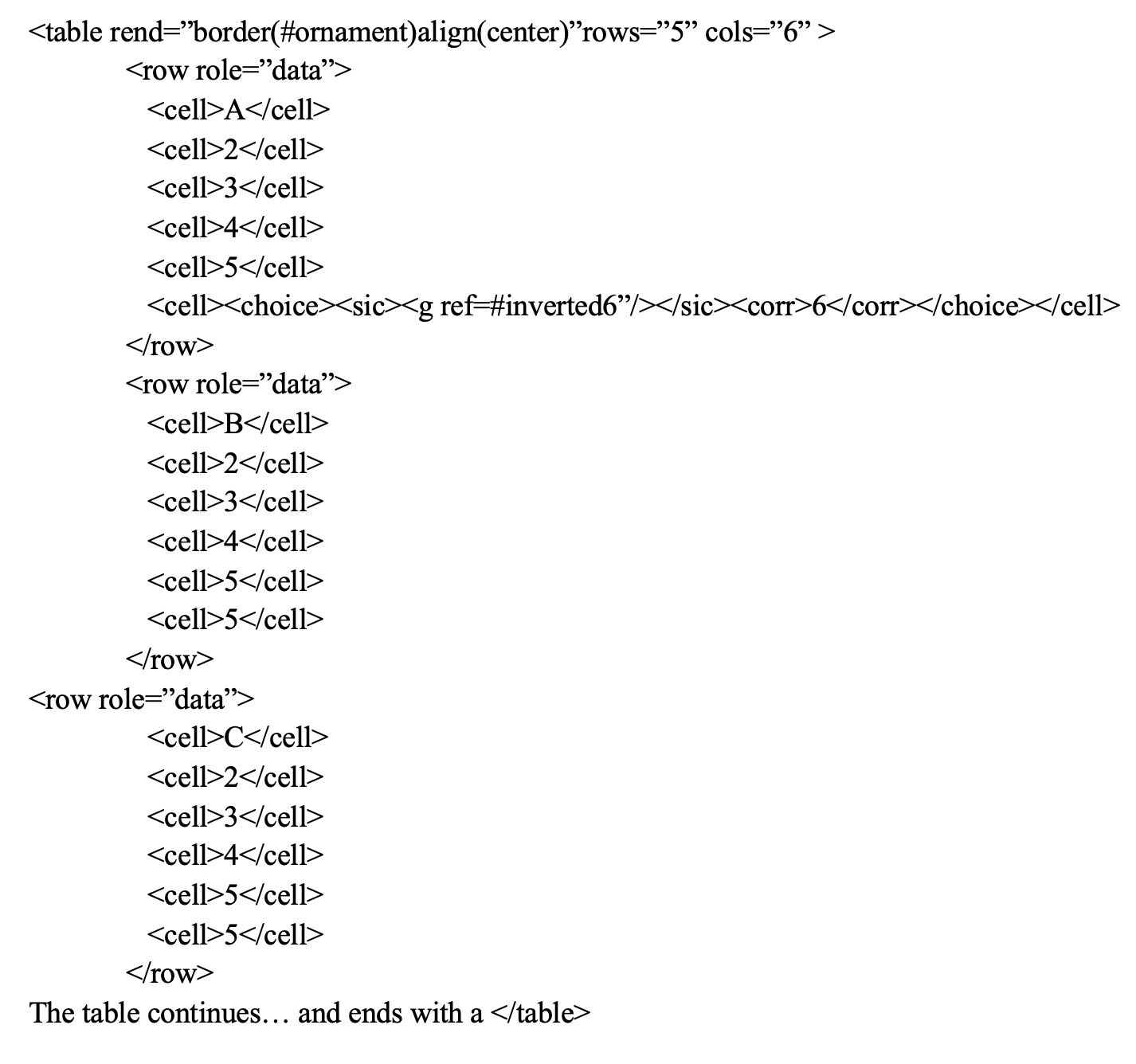

An obvious way to encode this table is by using the <table> element, but in looking at how this table is printed alongside what the markup looks like impacts how one perceives what they are looking at.The markup and image expresses the same information, yet when confronted with the two one processes the information differently. One challenging aspect of the encoding process was the fact that the physical document is missing information and as a result so is the markup.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum, Book, 19.

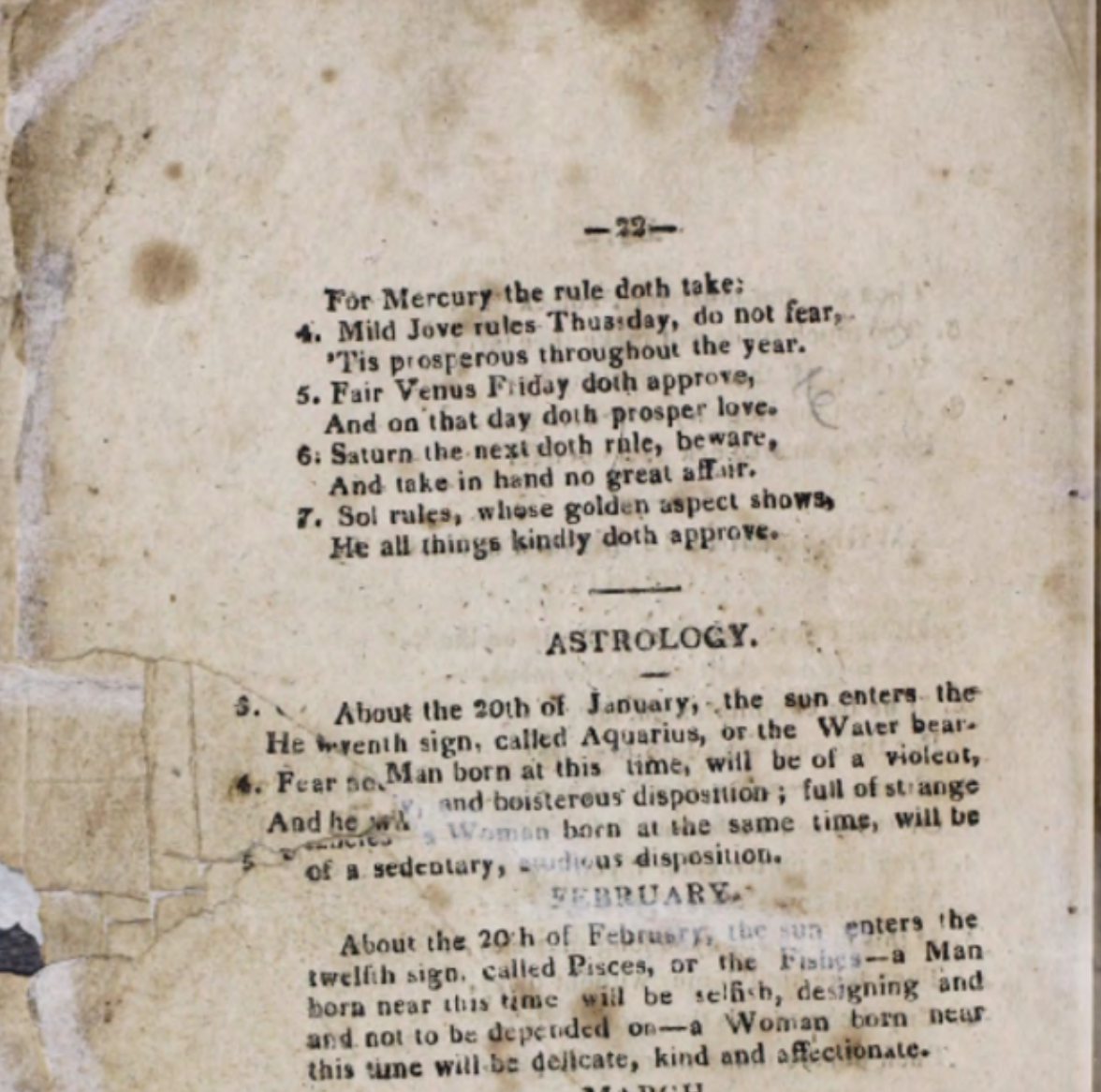

Above you can see that part of page 22 has been lost. This is both a loss for readers of the physical text and the encoded version as when information is missing from the original copy encoders must use the <gap> element to express that there is a certain extent of the text that is not available. Luckily there are not many sections in The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book that are either too damaged to understand or missing a large portion of the text.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum, Book, 22.

Implications for Chloe Russel’s Text

TEI opens up a multitude of opportunities for anyone who wants to encode text.There is a wide range of possibilities to encode The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book; such as gendered language, the role/representation of race, the connection to witchcraft and nature-based religion, etc. Encoding opens up a realm of possibilities that can be used to understand all of the nuances of this work. Looking at this work in conversation with others allows for “an opportunity to use the structural markup within the texts to create more intelligently focused searches, and it presents the search results in a way that could be used to read patterns across the entire collection.”3 Lastly, digitizing The Complete Fortune Teller & Dream Book makes the text more accessible and raises awareness about the large role Black women played throughout this time.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum, Digitized Book, EBBDA.

Endnotes

1 Connell, Sarah, Flanders, Julia, Keller, Nicole Infanta, Polcha, Elizabeth, and Quinn, William Reed. "Learning from the Past: The Women Writers Project and Thirty Years of Humanities Text Encoding." Magnificat Cultura I Literatura Medievals (2017).

2 Cummings, J. Opening the book: Data Models and Distractions in Digital Scholarly Editing. Int J Digit Humanities 1, (2019) 179–193.

3 Connell, Sarah, Flanders, Julia, Keller, Nicole Infanta, Polcha, Elizabeth, and Quinn, William Reed. "Learning from the Past: The Women Writers Project and Thirty Years of Humanities Text Encoding." Magnificat Cultura I Literatura Medievals (2017).

Bibliography

Connell, Sarah, Flanders, Julia, Keller, Nicole Infanta, Polcha, Elizabeth, and Quinn, William Reed. "Learning from the Past: The Women Writers Project and Thirty Years of Humanities Text Encoding." Magnificat Cultura I Literatura Medievals 4 (2017): 1. Web.

Cummings, J. Opening the book: data models and distractions in digital scholarly editing. Int J Digit Humanities 1, 179–193 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42803-019-00016-6.