Created by Helen Wang

Introduction

What constituted intellectual property theft in the early 19th century is very different from our understanding of it today. Capitalism and colonialism complicated our understandings of plagiarism and authorship, particularly drawing from the long history of white appropriation of Black texts. All of these issues affect how we read Chloe Russel’s text in addition to understanding the “true” authorship of Russel’s text and how these issues of authorial ownership are thought of/imagined.

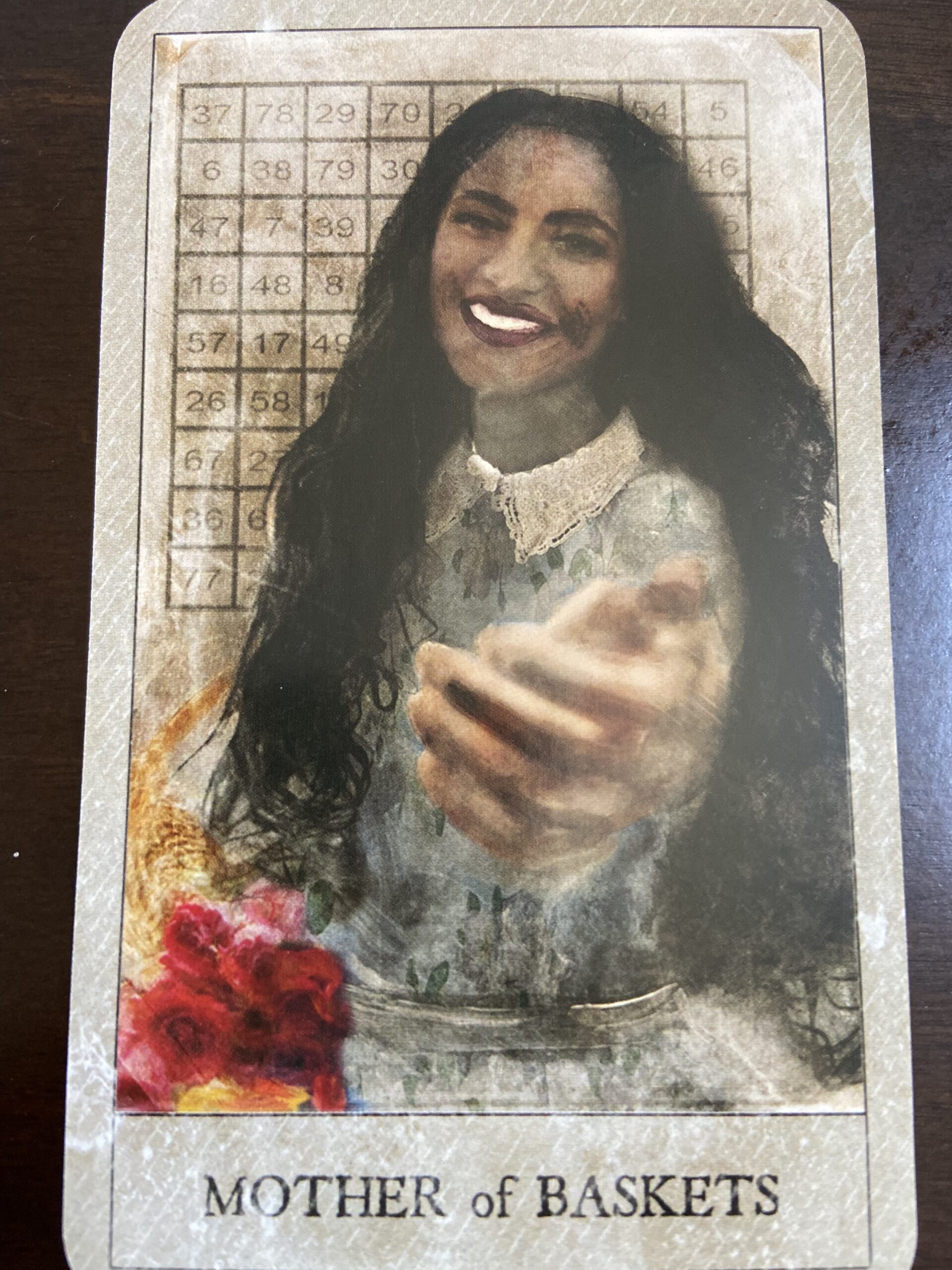

McQuillar, Tayannah Lee, and Katelan V. Foisy. 2020. The Hoodoo Tarot: 78-Card Deck and Book for Rootworkers. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books.

THE ORIGINS OF ORIGINALITY

The nature of what an author is changes over time. The writer had previously been "represented as one among many craftsmen involved in the production of a book" now the author stepped into the "central producer of a text."1

The meaning of "plagiarism" also shifted with changing literary norms. For neoclassical writers like Phillis Wheatley Peters plagiarism was solely "the reemployment of word-for-word particulars" or "verbatim parallels.”2 The definition of plagiarism which became "culturally dominant by the 1790s" was far more expansive.3 Changing legal norms "defined authorial style, sentiment, and tone as elements of literary property."4 Though an author could be charged with plagiarism for "unacknowledged or wrongful use” of,``''similarities in style, tone, and 'spirit'" were also fair game.5

Plagiarism was a major point of dispute for writers on both sides of the Atlantic. Ellen Weinauer lists "Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Richard Henry Dana, Nathaniel Parker Willis, Fanny Fern, Harriet Beecher Stowe, James Russell Lowell, and Rose Terry Cooke" as being among the American writers involved in plagiarism scandals--and those were only the white authors.6

As plagiarism persisted, a "long-ranging battle over copyright" was fought over in the US legislature. Copyright protections in the US were pretty relaxed in the nineteenth century.7 The Constitution focused on access to knowledge instead of intellectual property rights. For most of the 19th century the copyright law "offered protection only to certain types of texts for a finite duration of time, unlike the current law which extends copyright seventy years after the death of the author.8

COMPLICATIONS OF CAPITALISM AND COLONIALISM

These 19th-century discourses of originality and intellectual property were always complicated by issues of capitalism, colonialism, and race. Friction between the British and American publishing worlds in the 19th century arose as a result of conflicting copyright laws. Because American copyright law only covered American nationals until 1891, a common practice for American printers was to reprint works by British authors at low cost because they didn't need to worry about paying the author or the original publisher. "Reprinting foreign works was culturally and legally legitimate and even patriotic" in this environment.9 Debates over copyright "were framed in such a way as to pose the elitist English authors against the humble 'everyman' of the United States."10

Monica Cohen writes, "For most of the century, the unauthorized reprinting of British titles formed the bulk of the American book trade. As early as 1820, it was estimated that 70 percent of the American book market as a whole consisted of works by British authors."11 High literacy rates and technological advancements made writing and printing more accessible. This led to the development of a middle class with leisure time, which fed into "American piracy."12

Newly independent colonies in the mid-20th century lacked a "national literature," or that their styles were taken from the colonizer's art. Andrew Delbanco explains, "Some fifty years after the political establishment of the United States, the concept of an American literature barely existed--an absence acknowledged with satisfaction in Sydney Smith’s famous question posed in 1820 in the Edinburgh Review: 'Who in the four corners of the globe reads an American book?'" Up until the mid-19th century, American literary critics questioned if "American literature" was a genre. Literary movements like the American Renaissance and a wave of American literary nationalism attempted to address this question.

In 1907, another critic wrote "We have one series of literary productions that could be written by none but Americans, and only here; I mean the Lives of Fugitive Slaves. Essentially saying the Black culture was held to be solely“American” while cultural and social institutions were continually marginalizing, disenfranchising, and silencing actual Black Americans.

“PLAYING IN THE DARK”

Thomas Jefferson (1785):"Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but no poetry... Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately [sic]; but it could not produce a poet"

Black writers had a complicated relationship with replication and originality. Slave narratives, a genre Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Charles T. Davis calls "the beginnings of the Afro-American canon,”a resisted genre where literary skills and integrity of Black writers were put on trial.13 Slave narratives were closely read for any factual inaccuracies that would suggest the narrative--and its critique of slavery--were inventions of white abolitionist publishers and writers.

The scandal over James Williams's 1838 fabricated slave narrative (published seven years before Douglass's) illustrates how both abolitionists and slavery sympathizers found it impossible to imagine a Black writer possessing creativity and technique to essentially write an anti-slavery novel. Williams's "false" narrative was an example of "the pseudo-slave narrative," a supposedly nonfictional work about an escaped slave's life that was not actually written by a formerly enslaved person, a "small but vigorous subgenre of the slave narrative".14

Pseudo-slave narratives reveal obvious contradictions within the slave narrative industry. Slave narratives gained authority by conforming to certain stylistic norms. Slavery was portrayed more kindly than its reality; often disregarding or leaving out the awful atrocities of slavery for fear that they would strain the reader's belief. White abolitionist editors warned writers like Frederick Douglass "to avoid analysis or political critique," not to mention stylistic literary, to present the level of narrative complexity a white reader would expect from a former slave.15 In order to appear authentic, even "genuine" slave narratives were carefully managed and altered to confirm their readers' expectations.

"Pseudo-slave narratives are now considered largely embarrassing irregularities in the genre” [when they are even considered at all]" but the same urge to sort early Black writers as being either truthful and valuable or unethical and disreputable remains, such as in modern scholarly attempts to determine the authorship of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.16 Issues of fraud, authenticity, and imposture are bound up with pseudo-slave narratives.

While "black impersonators of fugitive slaves" were a major concern for the abolitionist movement, other pseudo-slave narratives were authored by white writers pretending to be Black.17 For example, white author Richard Hildreth pretended to be a slave named Archy Moore when he published The Slave in 1836. Christopher Castiglia suggests that writing Black characters, or adopting Black personas, "enhance[ing the] whiteness" of their writers, helping them to understand themselves as subjects.18

In her groundbreaking work of literary criticism Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison suggested that these attempts to "press black expression into the service of white authority" found in Blackness a figurative freedom from cultural norms.19 Morrison notes a long tradition of Blackface in American entertainment by noting how American writers were able to employ an imagined Africanist persona to articulate and imaginatively act out the forbidden in American culture."20 There is a "long tradition (from Stowe to Faulkner and beyond) of white authors taking and telling stories of black people."21 This appropriative tendency only works in one direction, however accusations of intellectual property theft, or even just a lack of originality, have been used to punish successful Black writers from Phillis Wheatley Peters to Nella Larsen.

"[Plagiarism] is not merely the highest literary crime which it is possible to commit, but it is the only literary crime which is never to be forgiven" – an article in the Caledonian Mercury, 1852

CHLOE RUSSEL’S COPYRIGHT CLAIMS

The authorship of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book remains in questions. "If Russel did author the work... then The Complete Fortune Teller might well require us to reevaluate the terrain of early African American literature... as an early slave narrative or... as one of the earliest examples of fiction by an African American woman."22 So how important is the identity of the creator to how we understand the text and locate it in its context?

As this exhibit has shown, the author, the owner of the text, and the writerly persona are not always the same thing. Chloe Russel may be the writer of the text, but not the author. She may have been a businesswoman who "capitalized" on the relationship between Blackness and mysticism, or she may have been the mask worn by a white publisher who exploited her image and racial stereotypes to sell books. Her six-page account of her enslavement and liberation may be "an early slave narrative" or simply a pseudo-slave narrative. The Complete Fortune Teller might rewire critical understandings of early Black literature or it might be literary Blackface. What can we say about The Complete Fortune Teller as it appears to us today--with an author whose identity we may never know?

Part of the answer to this question may be found in the aspects of the texts that have been appropriated themselves. Gardner notes that "a number of passages in... The Complete Fortune Teller or, an Infallible Guide to the Hidden Decrees of Fate," an anonymous text published as early as 27 years before Russel's text, "are identical to the work attributed to Chloe Russel, including much of the sections on dreams, palmistry, and moles."23 Though borrowing to this extent would be considered intellectual property theft today, in the 19th century, plagiarism was excusable if the plagiarist improved upon the source material. Russel certainly alters the context of the sections from the anonymous author of the earlier work. The juxtaposition of her dream interpretations with a slave narrative in which the dream the narrator has of her father deters her "from committing suicide the succeeding day" transforms the original materials.24

If Chloe Russel is both writer and plagiarist, she joins a tradition of Black literary luminaries who borrowed words to some extent, including Brown, Larsen, and Pauline Hopkins (who plagiarized from Brown). Gates Jr. sees recurring tropes in early Black literature as evidence that "the earliest writers of the Anglo-African tradition read each other's texts."25 Geoffrey Sanborn takes it a step further and suggests that plagiarism can sometimes be an indication of "a wide-ranging awareness of, and freedom with, the materials of one's culture."26 "Posing as an originator, the plagiarist unmakes old affiliations and creates new ones, giving the child a new parent, the slave a new master, the text a new author," and that is precisely what The Complete Fortune Teller does.27

Plagiarism is implicitly linked to kidnap, slavery, and the theft of self. "A 'plagiary' is one who abducts the child or slave of another, a kidnapper;... also... a literary thief.'"28 This definition suggests that the relationship between the author and the text is parallel to the one between parents and children, masters and slaves. The literary "thief" who intervenes in the property relationship between author and text "disrupts" the "claims of legitimacy and natural authority."29 If plagiarism disrupts hierarchies of ownership, Russel's plagiarism--and perhaps even the attribution of the text to Russel, whether she wrote it or not--is a kind of radical intervention in the logic of property that Russel. It breaks the relations of ownership between whoever actually authored the words--both the sections on palmistry and dream interpretation and her slave narrative--and forges new bonds with Russel.

Endnotes

1 Macfarlane, Robert. Original Copy: Plagiarism and Originality in Nineteenth-Century Literature(Oxford University Press, 2007) 27; Martin T. Buinick, Negotiating Copyright: Authorship and the Discourse of Literary Property Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Routledge, 2015) 4

2 Tilar J Mazzeo,Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) 12-13.

3 Tilar J Mazzeo, Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) 11

4 Tilar J Mazzeo,Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) 13

5 Tilar J Mazzeo, Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) 14

6 Ellen Weinauer, “Plagiarism and the Proprietary Self: Policing the Boundaries of Authorship in Herman Melville's ‘Hawthorne and His Mosses,’” American Literature, vol. 69, no. 4, (1997): 700.

7 Martin T. Buinick, Negotiating Copyright: Authorship and the Discourse of Literary Property Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Routledge, 2015) 1.

8 Martin T. Buinick, Negotiating Copyright: Authorship and the Discourse of Literary Property Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Routledge, 2015) 2.

9 Monica F Cohen, Pirating Fictions: Ownership and Creativity in Nineteenth-Century Popular Culture (University of Virginia Press, 2018) 3.

10 Martin T. Buinick, Negotiating Copyright: Authorship and the Discourse of Literary Property Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Routledge, 2015), 51

11 Monica F Cohen, Pirating Fictions: Ownership and Creativity in Nineteenth-Century Popular Culture (University of Virginia Press, 2018) 4.

12 Monica F Cohen, Pirating Fictions: Ownership and Creativity in Nineteenth-Century Popular Culture (University of Virginia Press, 2018) 4.

13 Henry Louis Jr. Gates, James Gronniosaw and the Trope of the Talking Book," The Southern Review, vol. 22 (1986): 252-272.

14 Lara Langer Cohen, The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture (Routledge, 2015) 102.

15 Lara Langer Cohen, The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture (Routledge, 2015) 102.

16 Lara Langer Cohen, The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture (Routledge, 2015) 102.

17 Lara Langer Cohen, The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture (Routledge, 2015) 108.

18 Lara Langer Cohen, The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture (Routledge, 2015) 110.

19 Lara Langer Cohen, The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture (Routledge, 2015) 128.

20 Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (New York: Vintage Books, 1992) 66.

21 Eric Gardner, "'The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book': An Antebellum Text 'By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour,'" The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2 ( 2005): 267.

22 Eric Gardner, "'The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book': An Antebellum Text 'By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour,'" The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2 ( 2005): 266.

23 Eric Gardner, "'The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book': An Antebellum Text 'By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour,'" The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2 ( 2005): 261

24 Eric Gardner, "'The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book': An Antebellum Text 'By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour,'" The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2 ( 2005): 267.

25 Henry Louis Jr. Gates, “James Gronniosaw and the Trope of the Talking Book," The Southern Review, vol. 22 (1986): 256

26 Geoffrey Sanborn, Plagiarama!: William Wells Brown and the Aesthetic of Attractions (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016)

27 Ellen Weinauer, “Plagiarism and the Proprietary Self: Policing the Boundaries of Authorship in Herman Melville's ‘Hawthorne and His Mosses,’” American Literature, vol. 69, no. 4, (1997): 700.

28 Ellen Weinauer, “Plagiarism and the Proprietary Self: Policing the Boundaries of Authorship in Herman Melville's ‘Hawthorne and His Mosses,’” American Literature, vol. 69, no. 4, (1997): 699

29 Ellen Weinauer, “Plagiarism and the Proprietary Self: Policing the Boundaries of Authorship in Herman Melville's ‘Hawthorne and His Mosses,’” American Literature, vol. 69, no. 4, (1997): 700.

Bibliography

Buinick, Martin T. Negotiating Copyright: Authorship and the Discourse of Literary Property Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. Routledge, 2015.

Cohen, Lara Langer. The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture. Routledge, 2015.

Cohen, Monica F. Pirating Fictions: Ownership and Creativity in Nineteenth-Century Popular Culture. University of Virginia Press, 2018.

Davis, Charles T. and Henry Louis Gates Jr. "Introduction: The Language of Slavery." The Slave's Narrative, Oxford University Press, 1991, pp. Xi-xxxiv.

Delbanco, Andrew. "American literature: a vanishing subject?" Dædalus, 2006, https://www.amacad.org/publication/american-literature-vanishing-subject.

Gardner, Eric. "'The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book': An Antebellum Text 'By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.'" The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, ( 2005): 259-288.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. "James Gronniosaw and the Trope of the Talking Book." The Southern Review, vol. 22, (1986): 252-272.

Hochman, Barbara. “"Love and Theft: Plagiarism, Blackface, and Nella Larsen's 'Sanctuary.'" American Literature, vol. 88, no. 3 (2016): 509-540.

Hochman, Barbara. “"Love and Theft: Plagiarism, Blackface, and Nella Larsen's 'Sanctuary.'" American Literature, 22 (2016): 509-540.

Macfarlane, Robert. “’Romantic’ Originality.” Original Copy: Plagiarism and Originality in Nineteenth-Century Literature. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Mazzeo,Tilar J. Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. New York: Vintage Books, 1992.

Olney, James. "'I Was Born': Slave Narratives, Their Status as Autobiography and as Literature." Callaloo no. 20. (1984): 6-75.

Sanborn, Geoffrey. Plagiarama!: William Wells Brown and the Aesthetic of Attractions. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Weinauer, Ellen. “Plagiarism and the Proprietary Self: Policing the Boundaries of Authorship in Herman Melville's ‘Hawthorne and His Mosses.’” American Literature, no. 4(1997): 697–717.