Created by Ariel Zweig and Savita Maharaj

Introduction

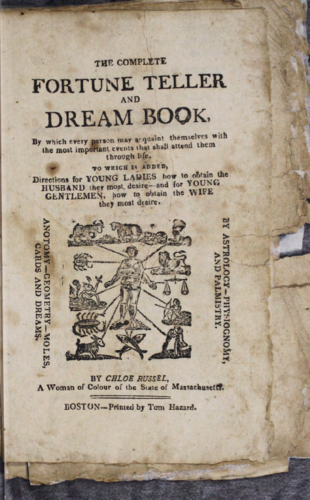

Of the four surviving copies of Chole Russel’s The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book, only one edition, which is held by the Library Company of Philadelphia, includes Russel’s autobiographical narrative. This begs the question of the narrative’s authenticity and the reason why it is in this edition and not others. Since the text’s front matter is lost, we do not know with certainty when this copy was published, and therefore cannot determine with certainty the timeliness of its publishing relative to the other known copies. The narrative offers a compelling backstory for the text’s author, describing her birth in Africa, journey by the Middle Passage, emancipation, and the establishment of a (lucrative) career as a fortune-teller. But because of the challenges, it presents as reference text—due to the fabrications it certainly contains—it also raises questions about genre. At face value, it is a slave narrative, and thus an interesting constituent of one of the early nineteenth-century book market’s more popular genres. But also, we may consider it as one of the earliest works of fiction about an African American woman, and possibly by an African American woman (since the historical Russel’s authorship is uncertain, we need to hedge on this point.)2

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book

I. Birth

The narrative begins, “I am a native of Africa, of the Fuller nation, and was born about the year 1745, about three hundred miles south west of Sierre Leone.” As Sierra Leone borders the Atlantic ocean on its south-west side, Russel certainly was not born “three hundred miles south west of Sierre Leone.” As Gardner notes, this would put her birthplace in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.3 In addition, the reference to the “Fuller” nation is also problematic as there was no nation then, nor now, known as “Fuller.” It may, however, be a “typographical variant of ‘Pular,’ a term connected with the Fulani people of West Africa.”4 The Fulani have been associated with several kingdoms throughout their history, including the Empire of Great Fulo from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. The Fulani people were then a significant demographic group of West Africa (where Sierra Leone is) so if Russel was born somewhere around Sierra Leone, it is certainly credible that she was Fulani.5 According to Gardner, the stated birth date of 1745, might also be problematic because the date conflicts with census records which record a Chloe Russell in Boston born no earlier than 1775.6 Thus, census records for Russell would have to be off by three decades in order to align with the narrative. However, given that we know that census records for Black women are not consistently accurate, as well as the fact that “exaggerating age was a common practice among [occultists], … and within African cultures where wisdom was thought to increase with age”7, it is possible that the birthdate has been deliberately placed earlier—that, or the narrative is fictitious or the name was a pseudonym.

“Map of Sierra Leone,” World Atlas.

II. Capture

In detailing her capture in Africa, the narrative states “Although I was but nine years old, I remember perfectly well the fatal day, when I was seized by the white men, and dragged from my parents and country.”8 Kidnapping was one of the main ways that Africans were enslaved, along with “warfare, … tribute, and enslavement through the judicial system.”9 Russel describes the terrible fear her people had of white people. “[W]e did not conceive them human,” she says, “but ranked them among the most ravenous beasts of the woods, which were always seeking an opportunity to seize and drag some of us to their dens, where we were torn in pieces to feed their young.”10. This fearfulness of whites she describes is similar to the description in many early African slave narratives such as The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, which foreshadows Russel’s sentiments when Equiano describes his first sight of white people aboard a slave ship, which convinced him that he “had gotten into a world of bad spirits and that they were going to kill me.”11 Russel’s fear of being cannibalized by white people is also similar to Equiano’s, who worried that he was going to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and long hair.”12 Although the descriptions of her capture in Africa are similar to those narrated by other enslaved Africans, the descriptions of “Lions, Tygers, Leopards, &c.” are inaccurate because while lions and leopards are found in Africa, there are no tigers.13

III. Middle Passage

The narrative also provides intriguing descriptions of the “Middle Passage’:“We were permitted to walk about the deck, but as more were continually arriving, the men I perceived were put down a great hole in the vessel, with irons upon their feet and hands.”14 This is a realistic description of the practice on board a slave ship. While the men would be “chained in pairs by the ankles” and held in the ship’s slave holds, women and children were “often allowed to remain on deck.”15 Russel notes that the enslaved Africans on board the ship were “of different tribes.”16 This too is realistic. Although her description of the diversity of the enslaved on the ships is accurate, her description of the results of an onboard revolt seem inaccurate. Killing “twenty or thirty” of the revolters would have been unusual (but not unheard of). The more standard practice was to kill only the leaders of the mutiny and flog the other participants.17 The enslaved Africans were, after all, economic assets to the White kidnappers.

“Slaves packed below and on deck,” New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1857.

IV. Slavery

The narrative also describes the experiences of enslavement in the southern United States. The narrative states, “In a few weeks after we were landed in Virginia, where we were sold at public auction—I was purchased by Mr. George Russel, a Planter, near Petersburg.”18 However, Gardner was unable to find documentation of a George Russel in the Virginia colony who matches the description that Russel gives in her narrative.19 However, the cruel treatment that Russel describes receiving from her second master is realistic and similar to that described in other narratives.

Lefevre James Cranstone, “Slave Auction, Richmond, Virginia, 1862,” 1862, Slavery Image, Oil Painting.

V. Freedom

The narrative details that Russell was able to eventually purchase her freedom.20 The price of Russel’s freedom, four hundred dollars, is likely accurate because it is comparable to the price paid by an enslaved Virginia man in a documented manumission in 1811 when Samuel Johnson paid five hundred dollars to purchase his freedom. Five hundred dollars was then an enormous figure. For comparison, the attorney for Johnson’s county in Virginia earned an annual salary of $270 at that time.21 Russel describes receiving the money in an exchange with a white planter. However, Gardner notes that interactions between the enslaved and whites who were not their master in Virginia were illegal. Furthermore, Virginia law was particularly hostile to the enterprise of manumission. Between 1723 and 1782, a law was in effect that stated “No negro, mullatto, or Indian slaves, shall be set free, upon any pretense whatsoever, except for some meritorious services, to be adjudged and allowed by the governor and council, for the time being, and a license thereupon first had and obtained.”22 Although this law was repealed after 1782, in 1806 a new statute was enacted which required freed slaves to leave the state within a year or be returned to slavery.23 Russel does not state the year of her emancipation, but it likely took place within the more favorable legal climate of 1782-1806.

Manumission of Francis Drake,”1791, Library of Virginia, Document.

Conclusion

Beyond the question of its genre, Chole Russel’s The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book examination of the narrative’s historical engagements/contexts also provides insight into the purpose of the text’s publication. It does so by showing when the author is probably fabricating, which allows us to consider why she fabricated and whom she fabricated for. This alone gives readers insight into the early nineteenth century.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book.

Endnotes

1 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005) 259–288

2 Ibid 269

3 Ibid 269

4 Ibid 2635 Johnston, H A S, The Fulani Empire of Sokoto (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 20

5 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005), 266.

6 Ibid 266

7 Ibid 269

8 Reynolds Edward, Stand the Storm: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1993), 33.

9 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005) 269.

10 Equiano, Olaudah; The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, First Published in 1789 in London, Is the Autobiography of Olaudah Equiano. The Narrative Is Argued to Represent a Variety of Styles, Such as a Slavery Narrative, Travel Narrative, and Spiritual Narrative. (1789)

11 Ibid 203

12 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005), 263

13 Ibid 270

14 Reynolds Edward, Stand the Storm: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1993), 48-9

15 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005), 270

16 Burnside, Madeleine and Rosemarie. Robotham, Spirits of the Passage: The Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Seventeenth Century (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Editions, 1997), 125

17 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005), 270

18 Ibid 263

19 Wolf Eva Sheppard, Almost Free: A Story about Family and Race in Antebellum Virginia (Race in the Atlantic World, 1700-1900)

(Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012),22-23

20 Ibid 19

21 “The Business of Freeing a Slave in Virginia.” The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. http://www.ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/page/view/m0153.

21 Ibid

Works Cited

Burnside, Madeleine and Rosemarie. Robotham, Spirits of the Passage: The Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Seventeenth Century. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Editions, 1997.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, First Published in 1789 in London, Is the Autobiography of Olaudah Equiano. The Narrative Is Argued to Represent a Variety of Styles, Such as a Slavery Narrative, Travel Narrative, and Spiritual Narrative., 1789.

Carretta, Vincent, ed. Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth Century. Expanded ed. Lexington, Ky: Univ. of Kentucky Press, 2008.

Franklin, John Hope, and Alfred A. Moss Jr. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans. Knopf, 1988.

Gardner, Eric. “The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book”: An Antebellum Text “By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005, pp. 259-88.

Johnston, H A S. The Fulani Empire of Sokoto. West African History Series. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Lefevre James Cranstone. “Slave Auction, Richmond, Virginia, 1862.” Slavery Image. 1862. Oil Painting. http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1969

“Manumission of Francis Drake,”, Library of Virginia. 1791. Document. https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/online_classroom/shaping_the_constitution/

“Map of Sierra Leone.” World Atlas. Map. https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/sierra-leone

Reynolds, Edward. Stand the Storm: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade. 1st Elephant paperback ed. Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1993.

Russell, Chloe. The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book.1824. Boston Athenaeum.

UNFPA Sierra Leone. “Sierra Leone 2015 Population and Housing Census National Analytical Report,” 2018. https://sierraleone.unfpa.org/en/publications/sierra-leone-2015-population-and-housing-census-national-analytical-report.

“Slaves packed below and on deck.”. New York Public Library Digital Collections.1857. Print. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-1bee-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Stenning, Derrick J. Savannah Nomads : A Study of the Wodaaoe Pastoral Fulani of Western Bornu Province, Northern Region, Nigeria. Münster; Hamburg: LIT Verlag with International African Institute, 1994.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. “The Business of Freeing a Slave in Virginia.” http://www.ouramericanrevolution.org/index.cfm/page/view/m0153.

Wolf, Eva Sheppard. Almost Free: A Story about Family and Race in Antebellum Virginia (Race in the Atlantic World, 1700-1900). Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.