Created by Nathalie Cruz

Introduction

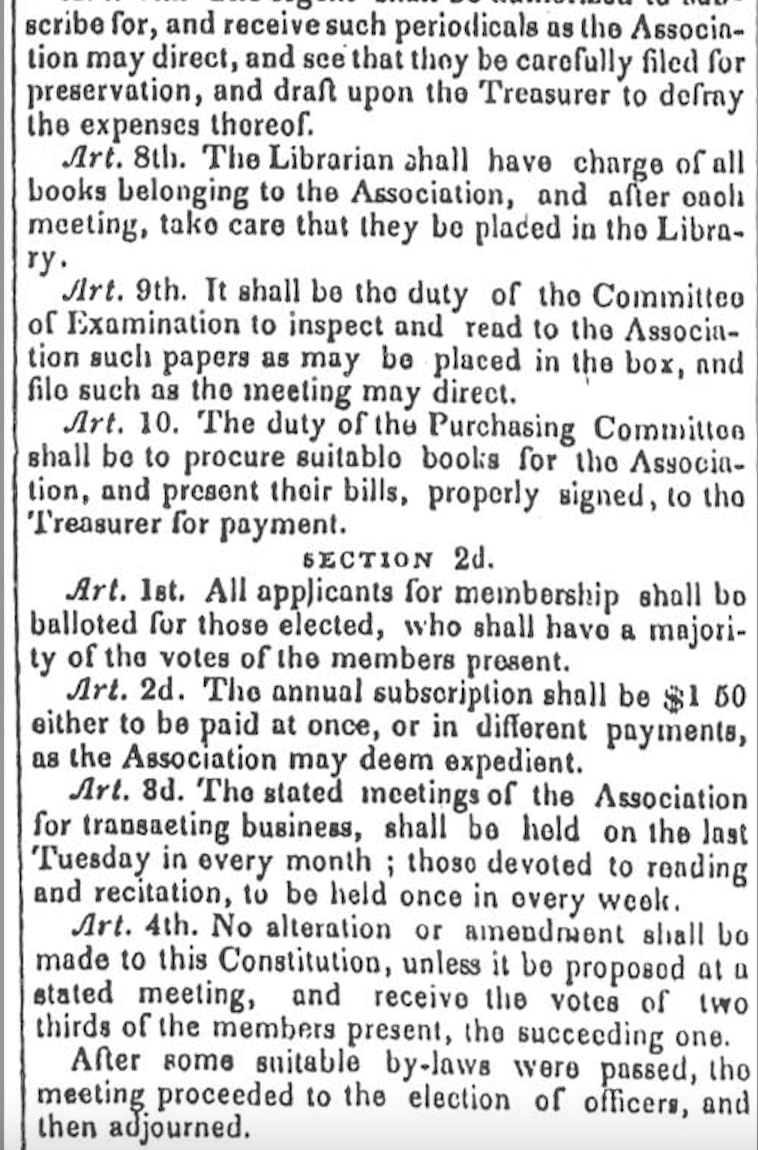

Much of the conversation around The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book has centered on the question of who wrote it. While the question of authorship is valid the question of readership, or who read it, might be a more intriguing one. As scholar Eric Gardner writes “the work raises fascinating issues concerning the role of African Americans in the antebellum literary marketplace.”1 Equally as important is the role of producers in this literary marketplace is the consumer.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book

Literacy rates for Whites and Blacks

According to the Massachusetts census of 1850, just 26 years after the publication of the Dream Book, 220,781 out of 985,450 (22.4%) White Americans counted in the census attended school. This starkly compared to the 1,439 out of 9,064 (15.9%) of African Americans who attended organized and formal school. These numbers illustrate the great disparity in formal education in Antebellum America. 27,539 out of 985,450 (2.8%) White Americans were considered illiterate, while 806 out of 9,064 (8.9%) African Americans were considered illiterate.2 These rates suggest a problem of illiteracy for African Americans, given the disparity in formal education in addition to the lack of funding for suggesting that white Americans had more access to all forms of published written works, in any genre.3 Although these flat rates of literacy do not reflect the actual trends and tendencies of literacy during this era, they do illuminate the fact that White Americans, overwhelmingly had more access to literacy than enslaved and free African Americans.

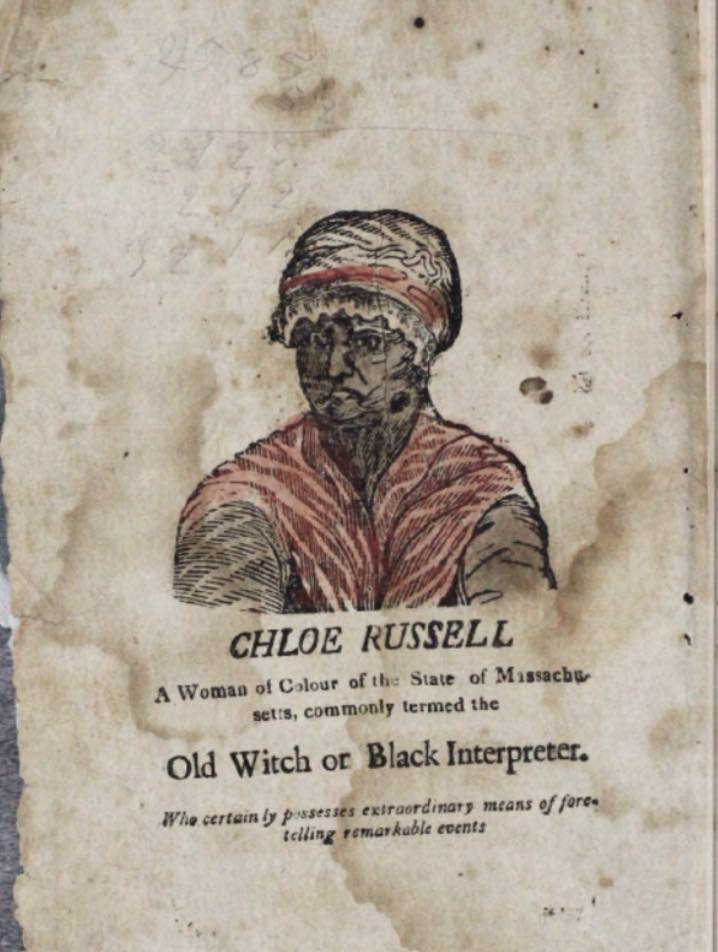

“Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church,” 1794, Richard Allen Museum and Archives, Photograph.

Because in Antebellum America there were fewer opportunities for African Americans to receive a formal education, many had to turn to alternative, informal educational spaces, such as churches and private tutors. Religious figures, like Richard Allenn, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (which Russel is said to have been a part of), championed education as the vital foundation for the liberty and independence of African Americans. He started a Sabbath School where children and adults could learn to read and write through Bible instruction. In this way, literacy was taught as more than the simple ability to read and write, but as an effort to “participate in all cultural institutions.”4 Likewise, all over the United States, including the South, organizations such as the American Missionary Association, opened Sabbath and night schools in order to instruct African Americans on literacy and mathematics, as well as religion and morality.5

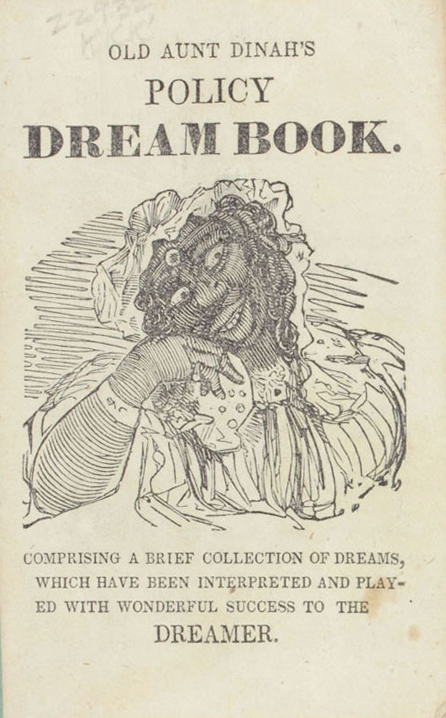

Old Aunt Dinah’s Policy Dream Book Comprising a Brief Collection of Dreams, Which Have Been Interpreted and Played with Wonderful Success to the Dreamer, Library Company of Philadelphia.1850. Book.

White Americans made up the largest segment of the population in Massachusetts and had higher rates of education and literacy. Consequently, they made up a huge part of the Antebellum literary marketplace and in all likelihood would have been the intended or assumed audience for literature such as the Dream Book. Though it was likely that White Americans would have had access to any published work, most of the reading would have been individual and at home and consequently affected by class, gender, and labor issues. For example, fathers or husbands often read aloud to other family members. Moreover, because 19th century reading practices were often tied to religion and notions of education, narratives such as Chloe Russel’s autobiography might have been popular with readers, but the actual content of the Dream Book would have likely been off-putting because it contradicted the mores of White Christian spirituality. Consequently, it is likely that The Dream Book simply would not have had that wide or powerful a circulation within White upper-class reading communities.6

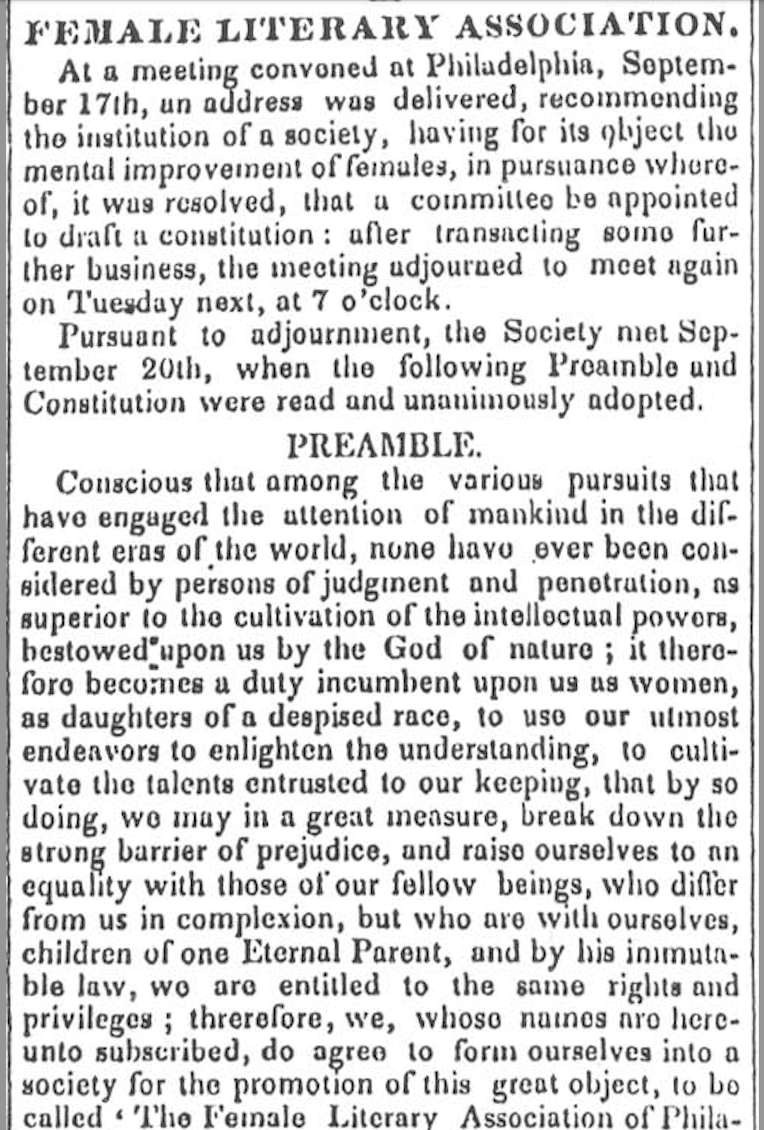

African American Literary Practices (Literary Societies)

Nineteenth-century African Americans, on the other hand, often developed other literary practices that were more accommodating to those who were unable to read. Like their White upper-class counterparts, orality and recitation were a large portion of these extra-literary practices, but typically this occurred on a more public scale in literary societies and educational spaces, rather than the centralized home. Despite the teachings of certain individual African American writers, like Frederick Douglass, African American literacy did not “valorize the power of formal or individualized literacy over communal knowledge.”7 The size and visibility of literary societies varied from officially recognized and organized societies to informal reunions in the home of some unnamed person. Many literary societies allowed membership that did not necessarily rely on any member’s actual ability to read or write; but instead cultivated an environment where African Americans could practice literacy communally and orally. Participation in literary societies did not require monetary access to books and literature because many shared access to libraries that were funded through membership.8 The missions of many literary societies were to foster intellectualism, empower African Americans, and prove that African Americans were capable of learning and independence. Some were organized with the specific goal of abolitionism, others with the organization and education of African American women, and others still with more social, though not less inherently political or intellectual, purposes.9

Many literary societies themselves fostered the writing of members, women and men alike, and created or reached out to publishers to make the writing of these members public. The writing produced and shared in literary societies ranged across many genres: slave narratives, autobiography, poetry, spiritualism, diaries, etc. It would not have been out of place for a book like Chloe Russel’s Dream Book to be shared. Additionally, because it was a common practice for formal and informal literary societies alike to read out loud or recite passages from memory, literature like the Dream Book would have been able to circulate to people who would not have had access to the text itself alone. African American literary societies allowed writers who would have been brushed aside by more ‘mainstream’ audiences a space where their writing could be circulated freely, discussed, and appreciated.

Constitution of the Afric American Female Intelligence Society of Boston, "The Liberator,” January 7, 1832, Boston, Mass.: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp, Newspaper.

Conclusion

While there is still so much we do not know, both about Russel and the literacy of early African Americans, we do know that this community of people existed, and further that they had their own literacy practices, and made an impact on the literary world. Understanding the possible readership of Early African American literature could shine a light on the ways that the literary world has changed over time and hopefully bring attention to the various groups of people that have been a huge part of the literary world without any official recognition. And though it is difficult to ascertain the veracity of Chloe Russel’s identity and authorship, we do know that the text was published and therefore read by someone. Determining who those ‘someones’ were or could have been could help solve at least part of the mystery around who the text would have impacted. As Russel wrote, “I have been induced to...furnish them with necessary directions, how by signs, tokens, moles, dreams &c. They may themselves determine the most remarkable events that should attend them through life.”10

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book

Endnotes

1 "The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850." The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850 - Massachusetts, www.census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850a/1850a-19.pdf.

2 Casper, Scott E. A History of the Book in America: Volume 3: The Industrial Book, 1840-1880. University of North Carolina Press, edited by Scott E. Casper, Jeffrey D. Groves, Stephen W. Nissenbaum, Michael Winship, David D. Hall, 2007 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=879962#.

3 Harris, Viola J. “African-American Conceptions of Literacy: A Historical Perspective.” Theory Into Practice, Vol. 31 No. 4. Tayler & Francis, 1992, pp. 276-286, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/1476309.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A183fdb3c381cc12cbf292359031c23eb.

4 Horton, James Oliver. Horton, Lois E. “Profile of Black Boston.” Back Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North. Edited by James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Revised Ed., Holmes & Meier: New York/London, 2000, pp. 1-13.

5 McHenry, Elizabeth, and Shirley Brice Heath. “The Literate and the Literary: African Americans as Writers and Readers—1830-1940.” Written Communication, vol. 11, no. 4, 1994, pp. 419–444 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0741088394011004001#articleCitationDownload

Container.

6 McHenry, Elizabeth. “Rereading Literary Legacy: New Considerations of the 19th-Century African American Reader and Writer.” Callaloo,

Vol. 22, No. 2. John Hopkins University Press, 1999, pp. 477-482, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3299496.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ad2a07c281952cbe09e0ddbbb0ccbdd1f.

7 Richardson, Joe M. Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861-1890. University of Alabama Press, 2009 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1047496.

8 Russel, Chloe. “‘The Complete Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly,

Vol. 78. Edited by Eric Gardner, The New England Quarterly, Inc., 2005, pp. 259-288, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/30045526.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A58b35d803716a46d27272f727ce2895d.

9 Winch, Julie. “‘You Have Talents -- Only Cultivate Them: Philadelphia’s Black Female Literary Societies and the Abolitionist Crusade.” The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America. Edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C. Van Horne, Cornell University

Press, 1994, pp. 101-118, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/10.7591/j.ctv1nhkdd.12.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A9aba6fe0e51803f85a038a4fabf86b1f.

10 Zboray, Ronald J. and Zboray, Mary Saracino.

“Reading and Everyday Life in Antebellum Boston: The Diary of Daniel F. and Mary D. Child.” Libraries & Culture, Vol. 32, No. 3. University of Texas Press, 1997, pp. 285-323, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/25548542.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae4661829395596b94166abf9c08c2a87.

“‘Have You Read…?’ Real Readers and Their Responses in Antebellum Boston and its Region.” Nineteenth-Century Literature, Vol. 52 No. 2. University of California Press, 1997, 139-170, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/2933905.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A3f3b63906941557e775c54d69d085fdc.

Bibliography

"The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850." The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850 - Massachusetts, www.census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850a/1850a-19.pdf.

“Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.” 1794, Richard Allen Museum and Archives. Photograph. https://coloredconventions.org/first-convention/introduction/

Casper, Scott E. A History of the Book in America: Volume 3: The Industrial Book, 1840-1880. University of North Carolina Press, edited by Scott E. Casper, Jeffrey D. Groves, Stephen W. Nissenbaum, Michael Winship, David D. Hall, 2007 https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=879962#.

Constitution of the Afric American Female Intelligence Society of Boston. January 7, 1832. "The Liberator,” Boston, Mass: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp, Newspaper. https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/9w032d75d.

Harris, Viola J. “African-American Conceptions of Literacy: A Historical Perspective.” Theory Into Practice, Vol. 31 No. 4. Tayler & Francis, 1992, pp. 276-286 https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/1476309.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A183fdb3c381cc12cbf292359031c23eb .

Horton, James Oliver. Horton, Lois E. “Profile of Black Boston.” Back Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North. Edited by James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Revised Ed., Holmes & Meier: New York/London, 2000, pp. 1-13.

McHenry, Elizabeth, and Shirley Brice Heath. “The Literate and the Literary: African Americans as Writers and Readers—1830-1940.” Written Communication, vol. 11, no. 4, 1994, pp. 419–444, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0741088394011004001#articleCitationDownloadContainer.

McHenry, Elizabeth. “Rereading Literary Legacy: New Considerations of the 19th-Century African American Reader and Writer.” Callaloo, Vol. 22, No. 2. John Hopkins University Press, 1999, pp. 477-482, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3299496.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ad2a07c281952cbe09e0ddbbb0ccbdd1f.

Old Aunt Dinah’s Policy Dream Book Comprising a Brief Collection of Dreams, Which Have Been Interpreted and Played with Wonderful Success to the Dreamer. Library Company of Philadelphia. 1850. Book.

Richardson, Joe M. Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861-1890. University of Alabama Press, 2009, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1047496.

Russel, Chloe. “‘The Complete Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78. Edited by Eric Gardner, The New England Quarterly, Inc., 2005, pp. 259-288, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/30045526.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A58b35d803716a46d27272f727ce2895d.

Winch, Julie. “‘You Have Talents -- Only Cultivate Them: Philadelphia’s Black Female Literary Societies and the Abolitionist Crusade.” The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America. Edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C. Van Horne, Cornell University Press, 1994, pp. 101-118, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/10.7591/j.ctv1nhkdd.12.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A9aba6fe0e51803f85a038a4fabf86b1f.

Zboray, Ronald J. and Zboray, Mary Saracino. “‘Have You Read…?’ Real Readers and Their Responses in Antebellum Boston and its Region.” Nineteenth-Century Literature, Vol. 52 No. 2. University of California Press, 1997, 139-170, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/2933905.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A3f3b63906941557e775c54d69d085fdc.

Zboray, Ronald J. and Zboray, Mary Saracino. “Reading and Everyday Life in Antebellum Boston: The Diary of Daniel F. and Mary D. Child.” Libraries & Culture, Vol. 32, No. 3. University of Texas Press, 1997, pp. 285-323, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/pdf/25548542.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae4661829395596b94166abf9c08c2a87.