Created by Blen Wondimu, Varun Jhamvar, & Savita Maharaj

Introduction

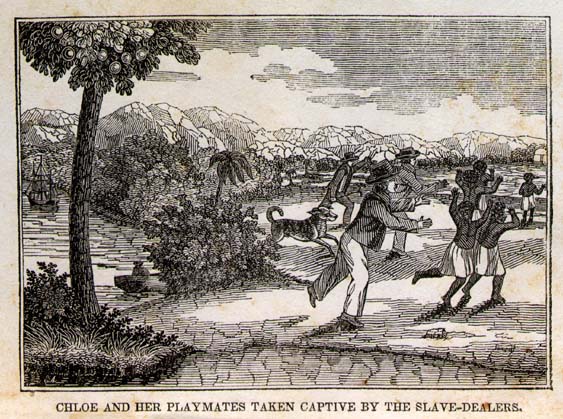

The exhibit provides context to Chloe Russell’s success as a fortune teller, homeowner, and businesswoman by examining the economic context of Black people, specifically Black women in Boston, during the 19th century. It examines the role of Black women in a Black household’s survival and how the necessity of work often barred them from participating in celebrated 19th-century assumptions about “true womanhood”.

The General Economic Context of Black People in 19th Century Boston

In the 1850s, most of the Black labor force in Boston was free. Domestic employment accounted for 71.5% of Black workers in Boston, including those in the hair and barbering, blacksmithing, and secondhand clothing trades.1 Less than a third of black Bostonians were skilled workers, which included professional roles like doctors, lawyers, teachers, or ministers (2% in 1860).2

Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton,“Profile of Black Boston,” 1999, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, Holmes & Meier, Book.

Black women often played a crucial role in the survival of their households through their income which supplemented that of their husbands’. Unlike white women who had the option of choosing not to work, many African women, in particular, relied heavily on domestic work such as caring for the wealthy's homes, working in boarding houses, and serving as laundresses. Steady employment was often hard to find for the majority of Black people in Boston. In Antebellum Boston, having lighter skin was considered advantageous and frequently evidenced by the greater employment for mixed-race Bostonians. However, they also accounted for 52% of the most skilled.3 For instance, in the the1850s, biracial people accounted for 18% of the Black workforce. This proportion increased in the 1860s when they made up 34% of the Black workforce. In addition to colorism, Black people experienced competition for employment and housing opportunities with immigrants such as those from Ireland who arrived in Boston in the 1850s.4 Black men were often disadvantaged when facing white competitors for the same jobs and faced resistance or objections from them. Moreover, the seasonal nature of Black men's work made it challenging to find reliable employment, making it nearly impossible for a Black household to be supported by a solitary bread earner. Additionally, immigrants often moved into the low-income neighborhoods that were also home to Black people. As a result, Black populations were sometimes gradually ‘forced’ out of some of these areas due to the inherent competition for space they faced from immigrants.

Cult of Domesticity and Its Consequences

In the 19th century, ideas about women’s participation in the workforce were heavily defined and influenced by the social ideology frequently referred to as the Cult of Domesticity, also known as the Cult of True Womanhood. As the name suggests, the Cult of Domesticity asserted that women’s primary spheres of influence should only be focused on home and family matters; it prescribed that women should possess four key features: piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity.

L. A. Godey, “A Sphere of a Woman,” 1850, Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. 40, P. 209, Book Illustration.

The rise of this ideology can be linked to the working-class struggle for a family wage (one wage that supports an entire family). The working class recognized that wages were lower when the supply of labor outstripped the demand for labor. While pursuing a family wage established a greater standard of living, the idea that every male worker was entitled to a wage that could support a family reinforced the idea that a woman’s work life was confined to the house's four walls–thus providing more impetus to the ideologies associated with the cult of domesticity. The focus on the family wage created stigmas for women who did work because it implied their husbands could not support them.5

Many of the repercussions of this ideology greatly affected women who had to work. Women mainly worked out of necessity. The cult of domesticity led to the denial of access to skilled jobs, lower wages, and more subordinate positions in the workforce. This mainly affected Black women, who were greatly impacted by the job segregation promoted by the Cult of Domesticity that relegated women to the least skilled and most poorly paid jobs.

The Nuances of Black Women’s Labor

After enslavement, both Black men and women believed that freedom should re-establish the “traditional” gender roles disrupted by slavery.”6 These aspirations were in line with the prescriptions of the Cult of Domesticity. There was strong advocacy for this shift in the antebellum North, but the financial realities of Black families limited their ability to participate in this ideal. Racism created conditions that prevented black men from accessing the family wage that would’ve allowed them to support their family through one source of income.

Woodruff, Hale, An Old Woman, [Between 1930 and 1950?], Library of Congress. Photograph.

In this way, Black women held an essential role in the family structure, giving them more independence and greater authority in their households and community. But alongside these gains remained cult ideas discouraging black women from working outside the home unless “absolutely driven by economic necessity.”7

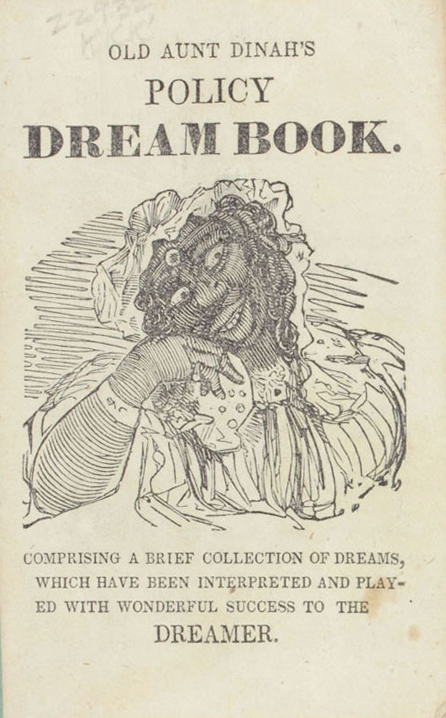

Old Aunt Dinah’s Policy Dream Book Comprising a Brief Collection of Dreams, Which Have Been Interpreted and Played with Wonderful Success to the Dreamer, Library Company of Philadelphia.1850. Book.

Consequently, the necessity of work for black women inherently denied them participation in the Cult of Domesticity. “The limitations under which all blacks labored brought poverty that made it impossible for black women to be ‘true women’ in the full nineteenth-century sense of that term.”8 Not only was it the ideal of womanhood that black women were denied, but it was also the economic security and possibility of upward mobility that white people were provided that reinstated the idea of colorism within 19th-century Boston. “The limitations imposed on women combined with those on blacks people t made the achievements of outliers like Chloe Russell and other successful businesswomen and property owners all the more significant.9

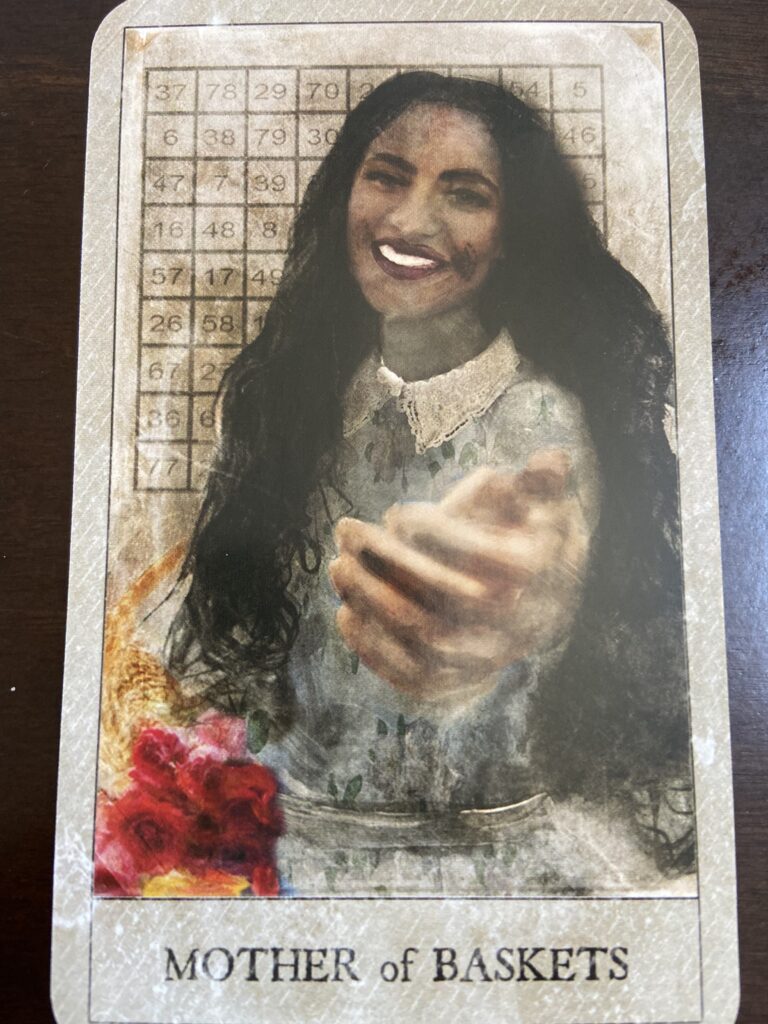

Contextualizing Chloe Russell: Other Black Female Businesswomen in New England

The question of Chloe Russell’s existence is one that has yet to be concretely answered. The information we know about her comes from her autobiographies, The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book, where readers learn how Russell’s prophetic ability gave her more socio-economic freedom and mobility. She had her freedom purchased by a man who bought her freedom for $400 and paid her $500, which she used to buy the home she ran her business.10 As she worked in Boston, she gained credibility and established a reputation for herself; in her autobiography, she writes that as she became more credible and her abilities clear, “great numbers began to flock for information.”11 Over 10 years of working, she accumulated $3,000, which she says she used to free other slaves. According to Boston tax records, Russell was one of only six women in Boston who owned property. It was also possible that Russell had a catering business that she was able to start through the profits she made as a fortune teller. Even more significant may be her ability to capitalize off the assumptions held by white people, which she made significant profits off, enabling her to run a successful business, buy property, and even help free other slaves. This awareness “suggests a smart businesswoman who knew her market.”12

Information on Russell and her book is limited to Eric Gardner’s text. Still, details regarding her significant upward mobility, work as a fortune teller, and successful businesswoman can be contextualized by examining other women who experienced similar successes.

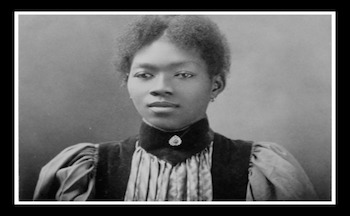

“Harriet E. Wilson,” African American Registry, Photograph.

Wilson began her career as early as 1861 after her son's death a year earlier.). She first appeared in the Banner of Light, a prominent Boston spiritualist weekly newspaper in mid-1867, in which the paper described her as “the earned and eloquent colored trance medium” and detailed her participation in a spiritualist convention where she spoke in a trance about labor reform and child education.13 Wilson’s growing status in the spiritualist movement was evident in 1868 when she was elected to the Finance Committee for the Third Annual Convention of the Massachusetts Spiritual Association – where she took charge of the convention’s monetary state of affairs.14 It is also reported that she volunteered to lecture for the Association free of cost.This is a notable distinction from Russell, who did turn fortune-telling into a successful business venture. Wilson's volunteer activity was a component of her networking activities and a means of getting accepted into a white-led group.

Wilson's trance work was impacted by other, more sensational forms of spiritualism, such as test mediums, that were becoming more prominent at the time.15 In response to this shift, Wilson’s claims grew more ambitious. She went from advertising herself as a “Lecturer and the Unconscious Trance Physician” to claiming she could treat chronic diseases with great success.16 This activity later waned. As she decided not to compete with the test mediums, her profits also decreased. In 1881 she described her private sessions as “an old-fashioned healing and developing circle.”17 Embracing the rise in interest in test mediums would have been difficult for her because her race made her status in the Spiritualist Movement more vulnerable.

Black Women Property Owners

Black workers and their families generally did not live in homes they owned. In 1850 only 1.5% of black single adults and family heads owned property; 1860, that percentage had only grown to 4.5%. In 1860, per capita property holdings for black people were $91 compared to $872 for the general population of Boston.18 One’s occupation or economic class did not predict property ownership.

Spear, Chloe, 1832, Memoir of Mrs. Chloe Spear, a Native of Africa, Who Was Enslaved in Childhood, and Died in Boston, January 3, 1815 ... Aged 65 Years. Boston, Book.

The few “Bostonians who succeeded in generating profits from their business enterprise used these profits to enhance their entrepreneurial activities”, sometimes through investments in real estate like in the case of Chloe Spear.19 Spear did domestic work for a prominent family in Boston, and like many black women, her jobs did not stop there. She took over management of the boarding home she and her husband ran after this employment. She also looked after her family and accepted laundry at night to earn extra money. She later expanded the business into a laundry and amassed a considerable estate.20 While it was customary at the time, Spear did not place her wages under her husband’s management like women were expected to do so in the early 19th century. She spent $700 on her own to purchase the house. Only because married women were not allowed to buy property in their names under the law was her husband involved in the transaction.

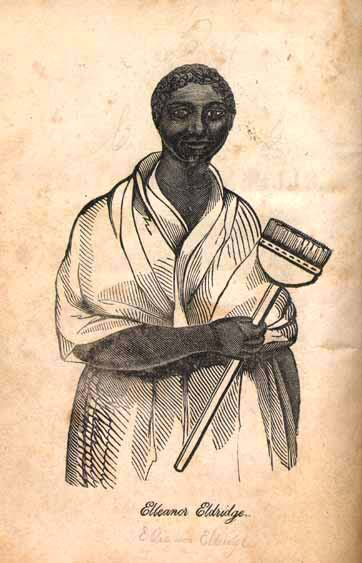

Elleanor Eldridge was another property owner and business owner like Russell and Spear Eldridge first worked numerous domestic jobs, from being a laundress and weaver to an expert cheesemaker. She later bought a lot of land in Providence, Rhode Island, and built a home she partially rented.

“Elleanor Eldridge,1840, Portraits of American Women, The Library Company of Philadelphia, Photograph.

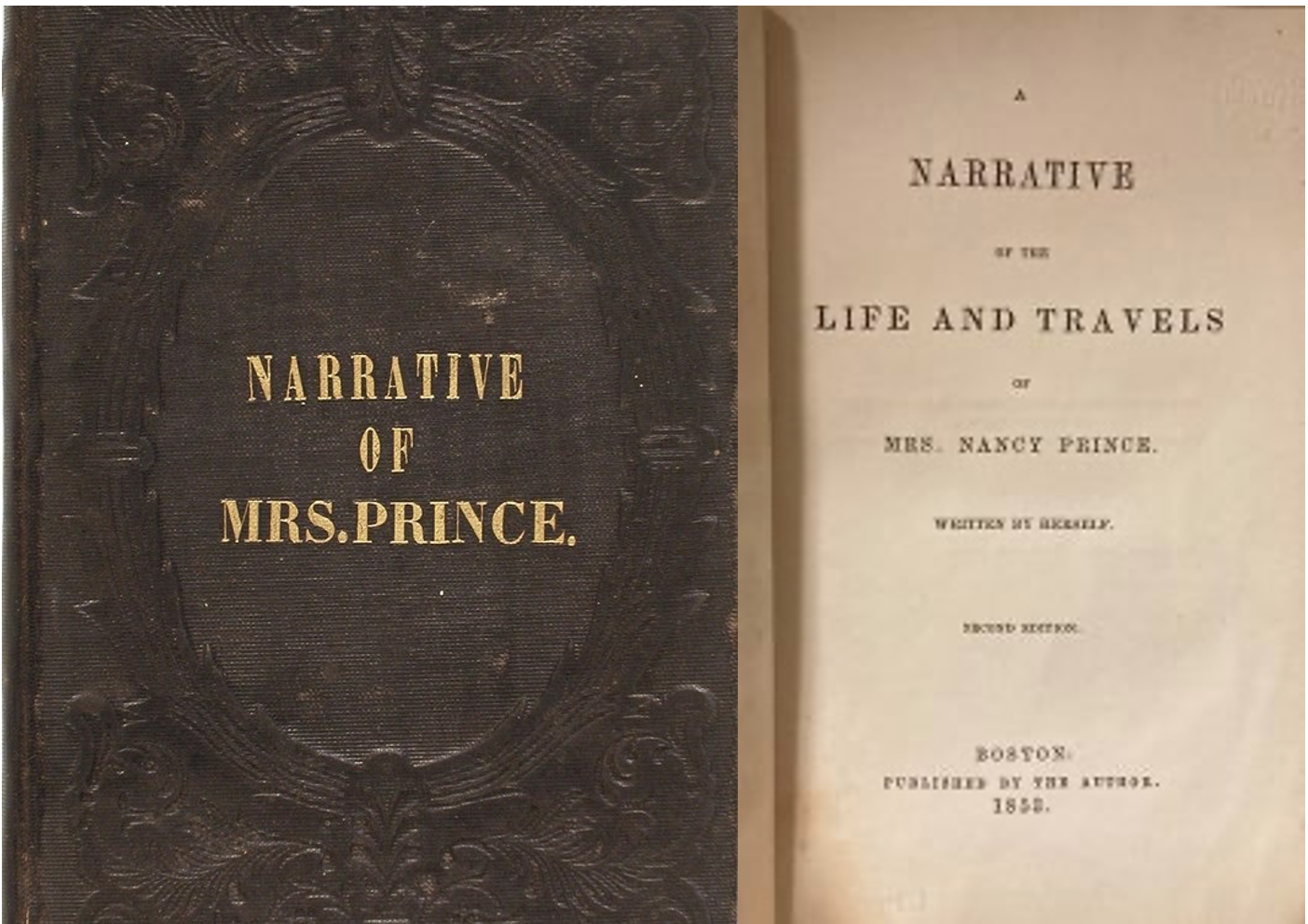

Prince, Nancy, 1853, A Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince. Book.

Nancy Prince was a seamstress who lived in Russia for nine years operating a fine clothing business for babies and children. The Russian Empress was one of her customers, and her company was successful enough for her to hire other individuals as journeywomen and apprentices. After returning to Boston, she self-published an autobiography in 1850 titled Narrative of the Life and Travel of Mrs. Nancy Prince.

Mary Edmonia Lewis, another businesswoman and sculptor that worked outside of the United States, achieved an international reputation as the first Black and Native American professional sculptor. She worked in Rome as a successful artist from 1865 to the 1880s. As a businesswoman, she is also known for her innovative strategies to sell her work, such as newspaper advertising, subscription campaigns, and actions.21

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, "E. Lewis. Sculptor," 1870-1879, Photograph

Conclusion

In conclusion, the economic circumstances of black women in antebellum Boston were generally marked by severe inequality and prejudice. Despite these challenges, some people were successful, but many others struggled to make ends meet and had few options for upward social and economic mobility. Hence disrupting the “traditional” narrative associated with Black women and their economic independence in early Boston.

Endnotes

1. Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton.“Profile of Black Boston.” Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1999)

2. Ibid

3. Horton, James Oliver. “Freedom's Yoke: Gender Conventions among Antebellum Free Blacks.” (JSTOR, 1986) 51–76.

4. Ibid

5. Geschwender, James A. “Ethgender, Women's Waged Labor, and Economic Mobility.” (JSTOR, 1992) 1–16.

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Horton, James Oliver. “Freedom's Yoke: Gender Conventions among Antebellum Free Blacks.” (JSTOR, 1986) 51–76.

9. Ibid

10. Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005) 259–288.

11. Russel, Chloe. The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book. 1827

12. Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005) 259–288.

13. Ellis, R. J., and Henry Louis Gates. “‘Grievances at the Treatment She Received’: Harriet E. Wilson's Spiritualist Career in Boston, 1868—1900.” (American Literary History, 2012) 234–264.

14. Ibid

15. Ibid

16. Ibid

17. Ibid

18. Horton, James Oliver. “Freedom's Yoke: Gender Conventions among Antebellum Free Blacks.” (JSTOR, 1986)

19. Black Entrepreneurs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries ( Museum of African American History, 2009)

20. Ibid

21. Ibid

Bibliography

Black Entrepreneurs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. May. - Sep. 2009, Museum of African American History, Massachusetts.

Blakely, Julia. “Her Story, Her Wrong: Elleanor Eldridge, the Narrative of a Free Black in Antebellum New England.” Smithsonian Libraries / Unbound, The Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, 4 Feb. 2020, blog.library.si.edu/blog/2020/02/04/her-story-her-wrong-elleanor-eldridge-the-narrative-of-a-free-black-in-antebellum-new-england/.

Ellis, R. J., and Henry Louis Gates. “‘Grievances at the Treatment She Received’: Harriet E. Wilson's Spiritualist Career in Boston, 1868—1900.” American Literary History, vol. 24, no. 2, 2012, pp. 234–264. JSTOR, www.jstor.org.ezproxy.neu.edu/stable/23249769.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005, pp. 259–288. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30045526.

Geschwender, James A. “Ethgender, Women's Waged Labor, and Economic Mobility.” Social Problems, vol. 39, no. 1, 1992, pp. 1–16. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/3096908.

Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton.“Families and Households in Black Boston.” Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, Holmes & Meier, 1999, pp. 15–26.

Horton, James Oliver. “Freedom's Yoke: Gender Conventions among Antebellum Free Blacks.” Feminist Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 1986, pp. 51–76. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/3177983.

Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton.“Profile of Black Boston.” Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, Holmes & Meier, 1999, pp. 1–13.

Russel, Chloe. The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book. 1827, Boston Atheneaum.