Created by Monae Cooper

Introduction

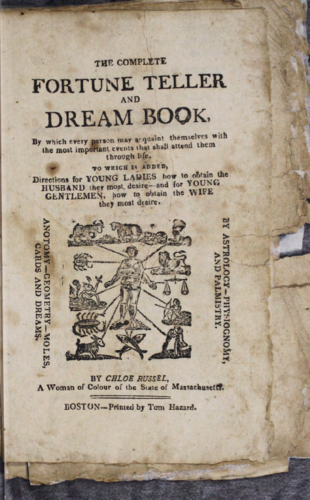

The existence of Chloe Russel’s The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book is evidence that she knew how to market her craft well enough to amass an audience, support herself and her family, and acquire property and wealth. Research into the economic conditions of the black community in Boston during the Antebellum period (1800-1860) will provide the proper context to understand the challenges that a female entrepreneur, like Russel, would have faced. The following five factors of Ruseel’s identity and environment, (1) Bostonian, (2) Female Head of the household, (3) African Native, (4) Property Owner, and (5) Entrepreneur have been researched from an economic perspective and examined to create a fuller understanding of the context that Russel lived and worked in.

McQuillar, Tayannah Lee, and Katelan V. Foisy. 2020. The Hoodoo Tarot: 78-Card Deck and Book for Rootworkers. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books.

1. BOSTONIAN

Boston and the New England area were believed to be a “mecca” for free Black people because of the many opportunities for advancement made available. In Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban American, 1750-186, historian George A. Levesque wrote, that between 1820-1860, “Blacks could vote, hold public office and testify in court; schools were desegregated, anti-miscegenation laws abolished, jim crow carriers abandoned, personal liberty laws enacted and noticeable inroads were made in striking down prohibitions which barred the social intermingling of the races in restaurants, hotels, clubs and theaters…”1

However, these advancements did not necessarily translate into economic opportunities. The economic structure of Boston proved to be a confining space for Black people to attempt to acquire gainful employment. Research into the probate records of antebellum Boston conducted by Carol Stapp reveal that, “Boston had little other than its port to offer in employment for the blue collar worker. The majority of black men therefore found work as mariners and dock laborers, both low-paying and irregular occupations…”2 Furthermore, Levesque’s research expresses the reflections of the following prominent leaders in the Black community who believed that racism and oppression were the primary causes of their dismal economic conditions.

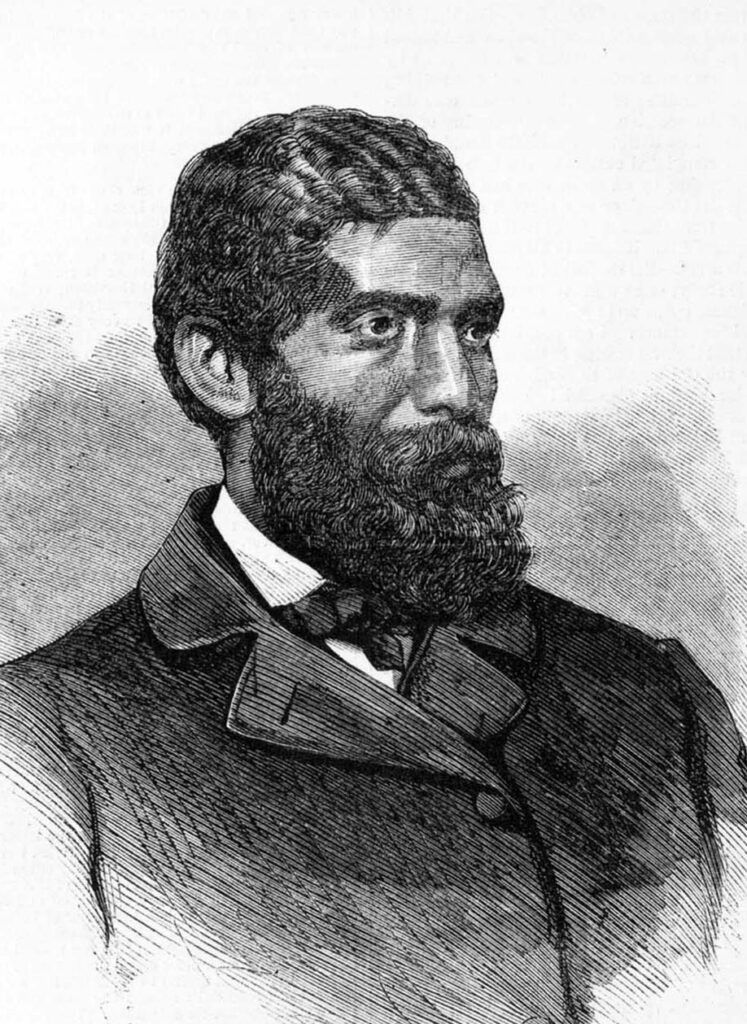

Dr. John S. Rock (1825-1866)

By the age of 27 Rock was a practicing dentist, physician, lawyer, and speaker for the abolition movement living in Boston. He was also the first African American lawyer to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court.3 Rock concluded that contrary to the social and political advancements, one should not conclude that northern Blacks did not have to face oppression or racism comparable to those in the South.4 Prejudice in the north resulted in minimal occupational opportunities. For example, even though blacks could attend school in Boston, Rock testified to the fact that;

Langdon, L.L. “John H. Rock," 1865, United States, Photograph.

“…there is no field for these men…not enough…in the whole United States to sustain, properly, a half dozen educated colored men,” it was, “ten times as difficult for a Negro mechanic to get work in Boston as it was in Charleston,” and, “menial employments…plentiful enough fifteen or twenty years past, were dying up.”5

This led people within the community to question if the political and social advancements were truly amounting to progress. Lastly, Rock argued that in a country based on capitalism, economic equality was the key to black people achieving true equality.

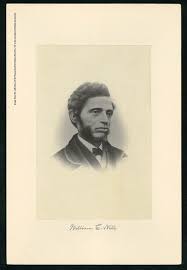

William C. Nell (1816-1874)

Born and raised in Boston, Nell was an activist, abolitionist, and historian. Mentored by William Lloyd Garrison while working as a member of the Juvenile Garrison Independent Society, Nell led the campaigns to desegregate the Boston railroad and Boston performance halls in 1843 and 1853.He was also one of the founders of the New England Freedom Association in 1842.6 Nell was not as extreme in his criticism of the economic conditions as Rock and others were. He believed that the “spirit of caste” that restrained economic advancement for black people would one day be mitigated as long as progress on the political and social end continued.7 However, similarly to Rock, he did acknowledge that Black mechanics and merchants were not given equal opportunity to work in their field. Thus, Nell used his position of power in the community to open a “Registry for Help” at 21 Cornhill Street for black people who were seeking employment.8

“William C. Nell.” Massachusetts Historical Society Photograph.

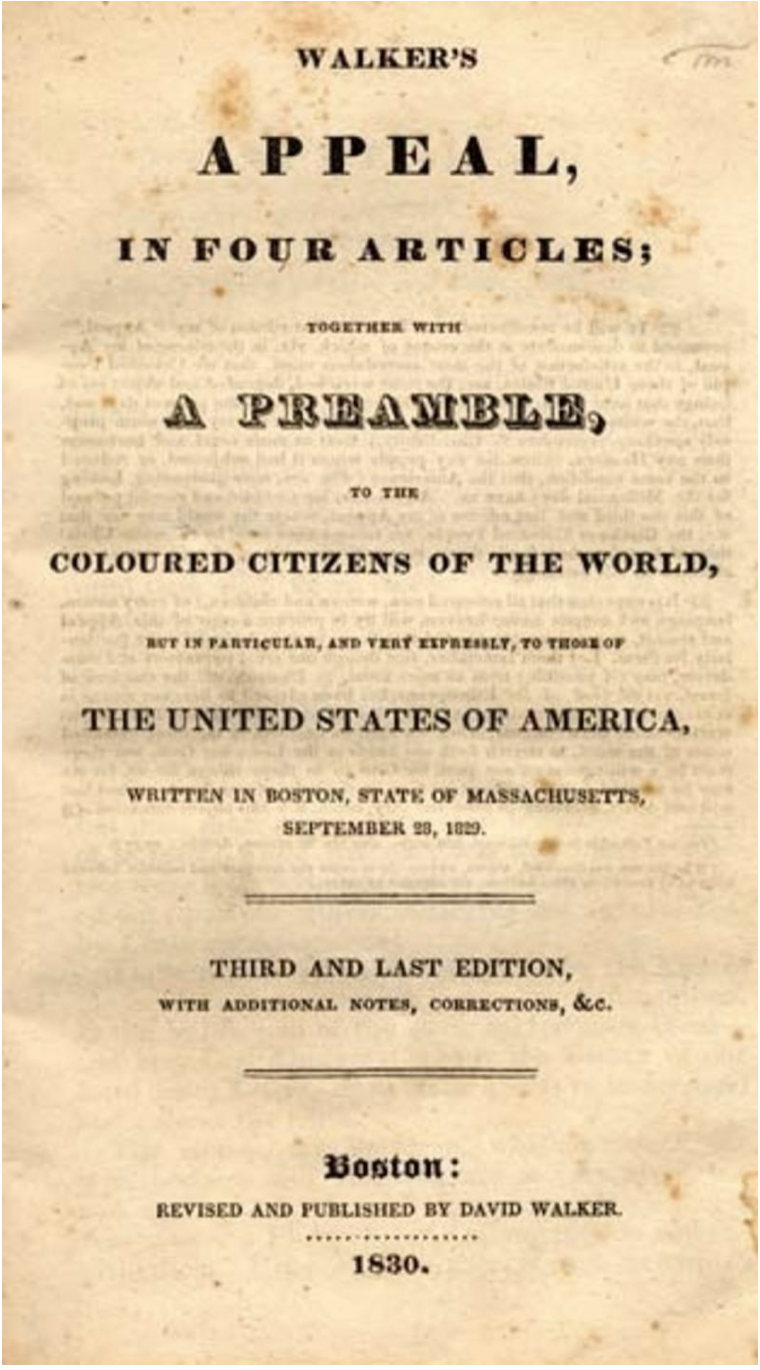

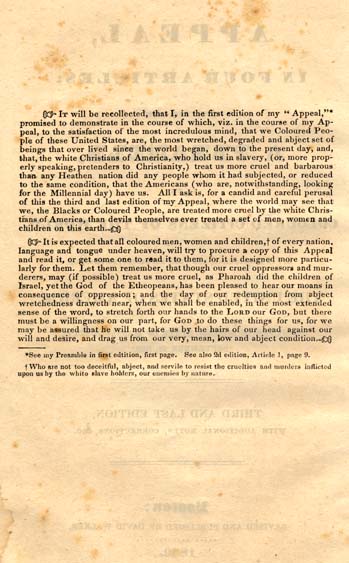

David Walker (1785-1830)

Born free in Wilmington, North Carolina, Walker moved to Boston in 1825 where he became a leader in the abolition movement. Most famously he wrote, David Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World published in 1829. Walker quickly gained recognition for his militancy as he continued to give speeches and write for the anti-slavery movement.9 Walker often commented on the lack of employment opportunities that were available to Black people and encouraged them “to aspire to higher attainments than wielding the razor and cleaning boots and shoes.”10 However, he also recognized that the real issue was not the lack of ambition from the Black community, but instead was that, “A colored man, however intelligent, is not allowed to pursue any business more lucrative than that of a barber, a shoe-black, or a waiter.”11 Walker concluded that the effects of racism and slavery were to blame for the economic condition of black people.

Walker, David, Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America, Written in Boston, State of Massachusetts, September 28, 1829, 1829.

Furthermore, there were significant demographic changes due to the dramatic influx of poor, white, Irish laborers in the 1830’s which worsened the economic condition of the Black community. Between 1830 and 1850 the entire foreign born population in Boston increased by approximately 200,000.12 Not only did the increased competition make it more likely that Black people faced unemployment, but also increased the likelihood that they would have to accept low-paying jobs. Stapp writes that:

"Boston’s blacks can thus be described as both integral and peripheral to their city’s economy. Shut out from competition with white Yankees, squeezed even more by the influx of Irish in the mid-1840s, blacks provided a pool of labor that could be hired or fired at will when commerce fluctuated."13

In Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, James and Lois Horton’s book, B, states that by 1860, the per capita wealth was $131 for the recently immigrated poor Irish community; whereas it was $91 for the black community.14 This combination of discrimination and increased competition ensured that the majority of Black Bostonians belonging to the workforce would not rise above the position of servitude. These harsh realities that many faced reflected that generally, white Northerners believed free black people to be a “menacing threat to the economic (and moral) well-being of white labour…”15 The statistician Jesse Chickering wrote in 1846 in regards to the black Boston population;

"A prejudice has existed in the community, and still exists against them on account of their color, and on account of their being the descendants of slaves. They cannot obtain employment on equal terms with whites, and wherever they go a sneer is passed upon them, as if this sportive inhumanity were an act of merit. They have been, and still are, mostly servants, or doomed to accept such menial employment as the white decline. Thus, though their legal rights are the same as those of the whites, their condition is one of degradation and dependence."16

Lastly, the lively Black community of Boston drew many to migrate to the city. Those who migrated into Boston from the south or other countries experienced an additional level of discrimination from within the black community. Author Lorraine Roses accounts in her book, Black Bostonians and the Politics of Culture, 1920-1940, that in the nineteenth century, “The infusion of southern Blacks irritated longtime residents who saw them as outsiders and who wished to associate only with those of a similar social status.”17

Walker, David, Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America, Written in Boston, State of Massachusetts, September 28, 1829, 1829.

2. Female Head of the House

It is not a surprise that many of the historical accounts and research done in regard to the economic condition of the Black community specifically speak about men. This can be attributed to sexism and that record-keeping during those times was inconsistent and oftentimes incomplete. However, this does not mean that women did not play a role in the economic vitality of the Black community. Black women not only had to deal with racism that excluded Black people from economic advancement, they had to deal with sexism that confined them to domestic labor.18 Research indicates that “Black women in antebellum Boston made up 90 percent of the occupational category of domestics, the category accounting for 20 percent of the entire black workforce.”19 Despite the fact that black women accounted for a fifth of the workforce, it did not equate to significant power outside the home for the majority of them. Stapp explains the “ironic” position black women held;

"It is now recognized that the ordinary Afro-American woman has borne a double burden. Being female and black, she has been required not only to live out gender ideals of deference to men but also to carry out economic and social roles — to raise her family and elevate her race — without questioning patriarchy or seeking autonomy."20

Woodruff, Hale, An Old Woman, [Between 1930 and 1950?], Library of Congress. Photograph.

The economic hardship that Black Bostonians faced forced women to have to play this complex role of “breadwinner” and the lesser gender. Racism and prejudice made it difficult for black men to have consistent employment that brought in a steady income to support a family. Thus, the financial support that working women provided was a major contributor to the survival of the Black community. Also, the economic struggles increased the number of households run by single women. While the destruction of the Black family is mainly seen as a legacy of slavery, Stapp poses the argument that a greater strain was put on the black family do the economic discriminations associated with the urban environment in the North. Continually, sexism proved to be nearly an insurmountable barrier that combined with racism “made total independence for black women all but impossible even as limited economic opportunities for black men made wifely dependence impractical.”21 Black women were forced to accept menial jobs that according to societal standards were proper for their race and gender. For instance, analysis of newspapers, letters, tax lists and additional records from the antebellum period in Boston indicate that taking in wash was the primary source of income for women.22 While the 1850 census does not record any single black washerwomen, the “Boston city directory indicated that there were at least twenty-five black women who took in laundry…the 1860 census listing thirty black washerwomen.”23 These numbers are believed to be a gross underestimation of the actual number of black washerwomen.

3. African Native

Scholars who study and research the history of the Black experience continually fight against the racist notions that the Black community was monolithic. Scholars have found that “…pertinent socioeconomic differences — occupation, geographic origin, skin color — within antebellum Boston’s black community that correlate with differences in residence, job skills, and association.”24 There is evidence of “disproportionate wealth and power.”25 associated with those of fair skin or characterized as mulattoes. The distinctions within the Black community in terms of color were reflective of the overall societal standards of the nineteenth century. The Hortons summarize that these standards, “equated beauty with light, even pale skin. For some Black Boston men, women who most closely approximated the white American image of beauty seemed particularly attractive.”26

This value placed on fairer skin resulted in tangible advantages from an economic perspective. In comparison to other northern Black cities, there were proportionately more mulattoes in Boston.27 Mulattoes were still a minority within black Bostonians in terms of numbers, but they were a majority in terms of wealth and power. Hortons write;

"Although mulattoes were only 18 percent of the black workforce in 1850, they accounted for one-quarter of the most skilled. By 1860 this overrepresentation was even greater. While mulattoes were 34 percent of the black workforce, they were 53 percent of the skilled workers."28

L. A. Godey, “A Sphere of a Woman,” 1850, Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. 40, P. 209, Book Illustration.

Not only did a lighter complexion result in more occupational opportunities, but also increased likelihood of property ownership. During the antebellum period, owning property was a rare occurrence. However, Stapp’s research indicates that mulatto women in Boston had more economic security than women of darker complexion that made property ownership more likely.

4. Property Owner

Owning property reflects the socioeconomic conditions of individuals, families, and communities at large. The rates of property ownership in Boston reflect the overall trend of wealth among black people that;

Afro-Americans were not in general amassing substantial amounts of wealth in the form of personal and/or real property. Systematically denied — either by law or custom — equal access to economic opportunities that would have yielded a comfortable income, or even an adequate one, blacks were not in a position to accumulate much in the way of personal and real property.29

Firstly, black families most likely lived in homes that were not their own.30 Additionally, by 1850 only 1.5% of single adults and family heads owned property. The rate increased to 4.5% by 1860 but that was believed to represent improvements in data collection and not actual increases in property ownership.31 As a result of the economic adversity that the Black community was facing in Boston, the practice of taking in boarders increased. In 1850, approximately one-third of households had borders; by 1860 that increased to about 40 percent.32 Traditionally, boarders were young, single adults who would only live with a host family until they married. However, “as financial opportunities dwindled, the period of boarding extended beyond the twenties so that by 1860 there was a rise in the number of those in their thirties and forties who were still boarding.”33

Lastly, Dr. John Rock compares the difficulty of home ownership in Boston with another prominent northern, urban city. He stated that, “It was five times harder for a black to get a house in a good location in Boston than in Philadelphia…”34

5. Entreprenur

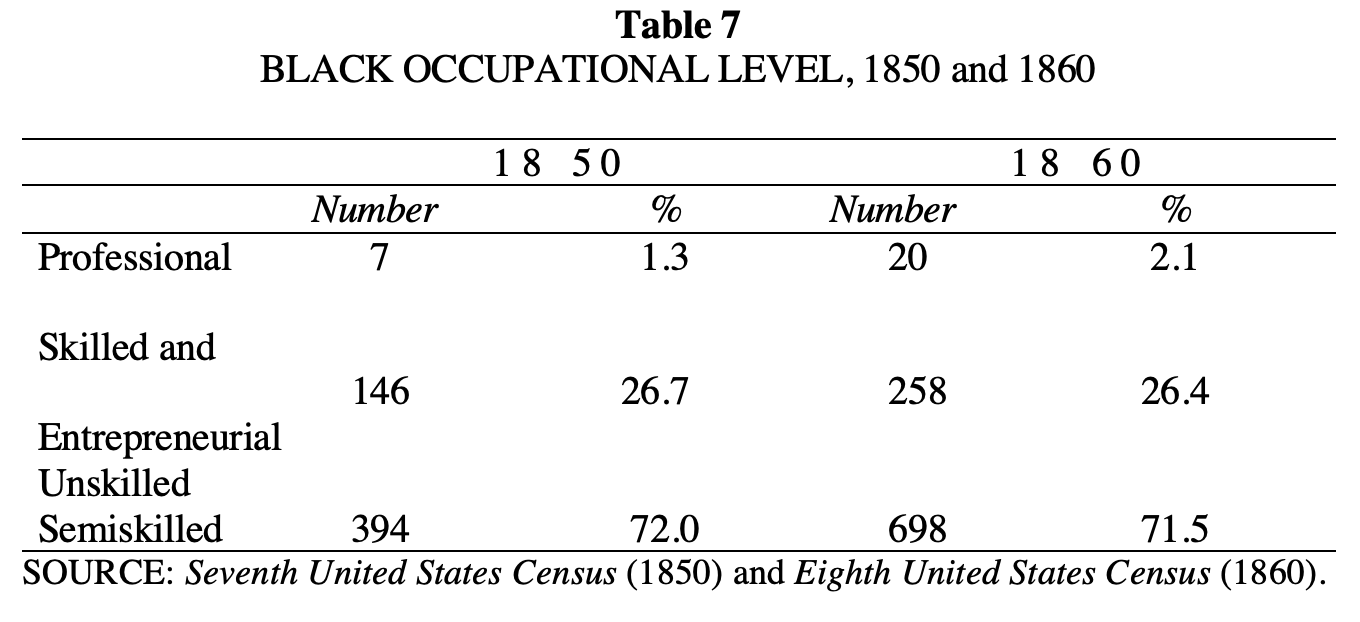

During the early nineteenth century, Black men in Boston mainly worked as unskilled or semi-skilled laborers accounting for 75% of the workforce.35 Less than one-third were considered skilled-laborers or shopkeepers.36 Achieving an occupational status above this was an aspiration for many but only a reality for few. As the Hortons note;

"Most at the bottom of the economic scale remained there throughout the antebellum period. Insofar as there was occupational mobility within black society, it occurred within the low-level occupational group — as the unskilled sometimes became semi-skilled. The rise of a worker into the skilled or entrepreneurial group was extremely rare."37

Unfortunately, achieving the status of skilled worker or entrepreneur did not make one immune to the economic trends, oftentimes many had to revert back to working lower skilled occupations. Levesque gives a more detailed description of the discrimination that black entrepreneurs faced that, “…operated to exclude them from the better paying industrial trades. Not only did whites refuse to teach blacks trades, ‘they combine to oppress, defraud and plunder a successful black mechanic or tradesman…and turn public sentiment against him by abuse and slander.’”38

Conclusion

The historical record could lead one to believe that the only choice presented to Black women was to succumb to the societal constraints placed on them due to racism and sexism. However, Chloe Russel’s text stands in opposition to that notion. Understanding the context of a Black, female entrepreneur brings a level of fullness to the personhood of Russ Russel did not let the societal structure that was designed to keep her confined stop her from aspiring and achieving more. Russel may not have been the activist that is so often championed from this period, but Chloe Russel offers a unique representation of the fighting spirit that has sustained Black people for over 400 years in this country.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

Endnotes

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Stapp, Buchalter Carol,“Part I.” Afro-Americans in Antebellum Boston: An Analysis of Probate Records (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ruffin, Herbert G. “William C. Nell (1816-1874).” Black Past, (2019)

- Ibid

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Gates, Henry Louis, and Valerie A Smith, editors. “David Walker (1785-1830).” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, ( 3rd ed., vol. 1, W.W. Norton & Company, 2014) 159–160

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Stapp, Buchalter Carol,“Part I.” Afro-Americans in Antebellum Boston: An Analysis of Probate Records (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton. “Profile of Black Boston,”Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 1–13.

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Ibid

- Roses Elena Lorraine. “Where Is Black Boston? Geographies of Experience in the Cradle of Liberty 1638-1900,” Black Bostonians and the Politics of Culture 1920-1940 (University of Massachusetts Press, 2017) 9–33.

- Stapp, Buchalter Carol,“Part I.” Afro-Americans in Antebellum Boston: An Analysis of Probate Records (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Stapp, Buchalter Carol,“Part I.” Afro-Americans in Antebellum Boston: An Analysis of Probate Records (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton, “Families and Households in Black Boston.” Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 14–26.

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton. “Profile of Black Boston,”Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 1–13.

- Ibid

- Stapp, Buchalter Carol,“Part I.” Afro-Americans in Antebellum Boston: An Analysis of Probate Records (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton. “Profile of Black Boston,”Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 1–13.

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton. “Profile of Black Boston,”Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 1–13.

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton, “Families and Households in Black Boston.” Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 14–26.

- Ibid

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

- Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton. “Profile of Black Boston,”Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (Holmes & Meier, 1979) 1–13.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Levesque. A. George, “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860 (Garland Publishing, 1994)

Bibliography

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, June 2005, pp. 259–288.

Gates, Henry Louis, and Valerie A Smith, editors. “David Walker (1785-1830).” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, 159–160. 3rd ed., vol. 1, W.W. Norton & Company , 2014.

Horton Oliver James, Lois E Horton.“Families and Households in Black Boston.” Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North,14–26. Holmes & Meier, 1979.

Levesque. A. George. “Is Boston Anti-Slavery?” Black Boston: African American Life and Culture in Urban America, 1750-1860. Garland Publishing, 1994. www.google.com/books/edition/Black_Boston/Ze1GDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&kptab=getbook.

Roses Elena Lorraine. “Where Is Black Boston? Geographies of Experience in the Cradle of Liberty 1638-1900,” Black Bostonians and the Politics of Culture 1920-1940, 9–33. University of Massachusetts Press, 2017.

Ruffin, Herbert G. “William C. Nell (1816-1874).” Black Past, 14 Nov. 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/nell-william-c-1816-1874/.

Stapp, Buchalter Carol. “Part I.” Afro-Americans in Antebellum Boston: An Analysis of Probate Records. Garland Publishing, 1993. www.google.com/books/edition/Afro_Americans_in_Antebellum_Boston/5Y2EDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&kptab=getbook.