Created by Kelly Flemming & Savita Maharaj

Introduction

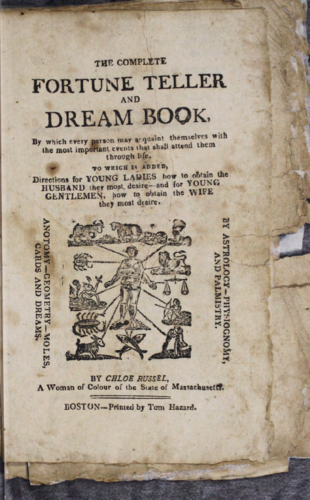

While the authorship of Russel’s text is unknown it is important to look at how Russel’s connection with Sierra Leonean divination speaks to her authorship. This exhibit contains a theory of Russel’s birthplace, background on the Atlantic Slave Trade’s connection to witchcraft accusations, information on Sierra Leonean diviners and Temne techniques of divination, and analysis of the connections to The Complete Fortune Teller. While some of these connections and theories may be tenuous, all together, they speak to a knowledge of Sierra Leonean culture that points strongly toward Russel’s authorship.

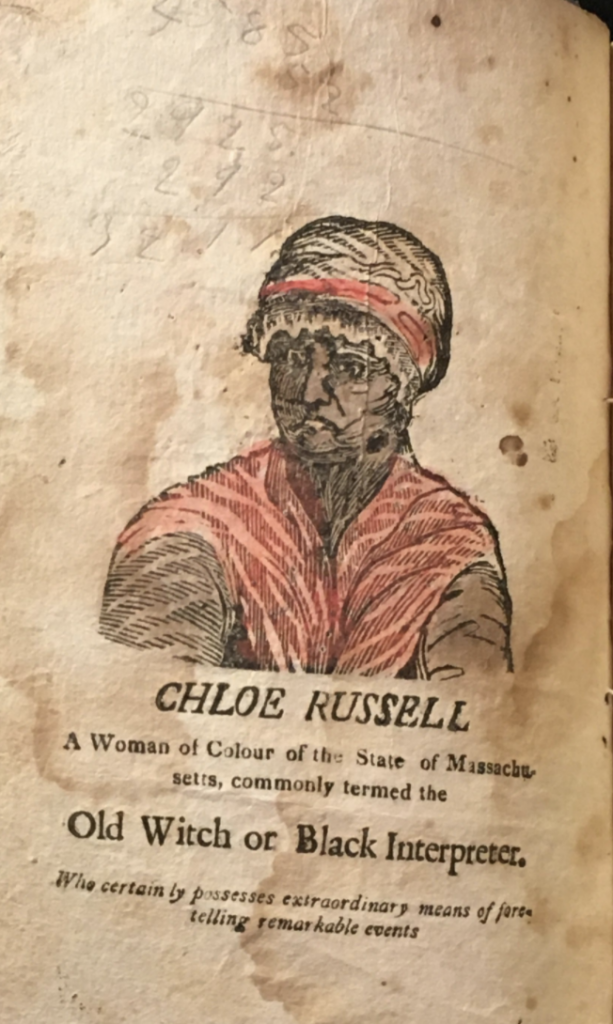

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

Russel and Sierra Leone

The Question of Russel’s Birthplace

Russel claims her birthplace is “the Fuller nation…about three hundred miles southwest of Sierra Leone.” Because Sierra Leone is a coastal nation, these directions would place a person squarely in the Atlantic Ocean.1 A closer examination of her Readers can contextualize this statement by looking at language Russel used in addition to the age at which she is kidnapped. The name “Fuller nation” could have been an anglicization of a Guinean ethnic group called the Fula. The Fula settled the western coastal region of Sierra Leone in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as merchants, Islamic teachers, diviner-healers, and herders. The Fula migrated from an area of Guinea known as Fouta Djallon at the time and was an ethnic minority in Sierra Leone at the time of Russel’s birth, estimated between 1775-1794.2 It is possible that the Fula considered themselves a separate nation from other ethnic groups in Sierra Leone, and Russel was referring to a social border that does not exist on American maps. If a publisher attempted to fabricate a birth in Sierra Leone, they would have been much more likely to cite the Temne or Mende people (the majority ethnic groups in the country).

“Map of Sierra Leone,” World Atlas.

While Russel’s assertion that this nation was 300 miles southwest of Sierra Leone may seem strange , readers must remember that she is recalling this distance as last perceived at nine years old — in a culture that did not measure distance in miles. Russel would have measured distance in days’ travel, a very different way of conceptualizing distance than miles. Professor Rosalind Shaw, an expert on Sierra Leonean divination, says "people who don't live in spaces divided into a geometric grid of miles by milestones or car milometers often give wildly 'wrong' guesstimates of distances and direction when they're asked how many miles away a place is."3

“Slaves packed below and on deck,” New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1857.

Russel likely would not have traveled often as a child because of the danger of the slave trade, obscuring whatever memory she had of the distance. There was often a lot of pressure placed on Black authors for accuracy surrounding their birthplace and stories in their narratives. Russell may have felt pressured, perhaps by her publisher, to come up with an exact location and decided on “three hundred miles southwest”. It’s also important to remember that Sierra Leone was defined differently in Russell’s time period. Before 1808, Sierra Leone would have referred to a coastal mountain range, hence the translation “Lion Mountain.” After 1808, the coastal area became known as the Crown Colony of Sierra Leone. If Russell lived far South of this area, she could have been born to Fula people somewhere along the coast of modern-day Sierra Leone or Liberia.4

Modern-day witchfinders in Sierra Leone (Crompton)

Witchcraft and the Atlantic Slave Trade in Sierra Leone

One of the earliest recorded accounts of witchcraft in Sierra Leone comes from a Portuguese printer, Valentim Fernande and was published between 1506–1507. Fernande recorded information from Alvaro Velho, a trader likely involved in the very beginnings of the Atlantic Slave Trade. He describes Sierra Leonean magical practices in the early fifteenth century, which included divination by “fetish-men” to find the cause of sickness and ritualistic burial practices. Sickness was often attributed to “idols,” and fetish-men would sacrifice animals to appease them. There is no mention of witch finding (witch identification through divination) or any persecution of those who practice magic.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the social climate of Sierra Leone changed. Mane invaders from the north began selling other ethnic groups in Sierra Leone to European slave traders. Manuel Alvares, a Portuguese missionary, recorded the change in divination practices at the time — instead of attributing sickness to idols, it was often directly attributed to next of kin or others in the village. When someone died, a sorcerer would interrogate the corpse as a part of standard burial practices, and ascribe the death to the witchcraft of another member of the village. This “witch” would be punished by the sale of themselves and all of their children to European traders.

Crompton, Greg, dir, Witches in Sierra Leone, YouTube, 14 July 2009 Journalists for Human Rights, Video

The Atlantic Slave Trade peaked in the eighteenth century, the time period in which Russel lived in Sierra Leone. The Fula people were one of many external groups in this time period that moved south into Sierra Leone, some for the purpose of participating in the slave trade. The English slave trader John Matthews attempted to justify the slave trade by blaming its immensity on the Sierra Leonean belief in witchcraft:

"Great number [of slaves] are prisoners taken in war…many are sold for witchcraft, and other real, or imputed, crimes; and are purchased in the country with European goods and salt…Though most unenlightened nations believe in charms and witchcraft, yet the inhabitants of this country are so much addicted to it that they imagine everything is under its influence, and every occurrence of life they attribute to that cause…if any person is taken suddenly ill, or dies suddenly, or is seized with any disaster they are not accustomed to, it is immediately attributed to witchcraft: and it rarely happens that some person or other is not pointed out by their conjurors, whom they consult on these occasions, as the witch and sold."5

Death was almost always attributed to witchcraft, and the accused were then sold into slavery. Even as some were sold into slavery for their magical practices, the conjurors or sorcerers that accused them were allowed to practice magic for this kind of divination. As in the Atlantic Slave Trade gained more traction, it seems that magical practices were demonized so that more people could be sold for a profit.When the Anti-Slave Trade Act of 1807 was passed by the British Parliament, the Atlantic Slave Trade began its decline. In 1825, English traveler Laing recorded a change in witchfinding practices in Sierra Leone. After witnessing the death of a young girl, the village elders suspected a witch to be the cause of death, but eventually attributed it to the Devil. Laing noted, “had the slave trade existed, some unfortunate individual might have been accused and sold into captivity.”6 Once again the source of illness and death returns to the unseen Devil, much like the idols referred to before the Atlantic Slave Trade. When the economic incentive for identifying witches decreased, so did the practice.7

“Divination Bowl,” British Museum.

As we saw during the Atlantic Slave Trade, witches were often persecuted as scapegoats for unexplained tragedies. While witches are thought to be evil, their magical counterparts, the “diviners,” are accepted in village life as healers, fortune-tellers, and witchfinders. These diviners are believed to acquire their powers from good spirits and ancestors, differentiating them from witches. The difference (between witches and diviners) is further solidified by the Temne idea of the human world and the hidden witch world where witches are thought to live within the witch world, while diviners can only contact this alternate world.

Divination is considered the opposite of witchcraft because it is used to enlighten: diviners use magic to reveal the unknown through fortune-telling, healing of mysterious illnesses, and witchfinding. While diviners have special and secret knowledge that other people do not, they use it for the service of the community. This does not mean that diviners are above suspicion for their special knowledge, but they do have an accepted and productive role in their society that the witch does not.

The Temne Diviner

The Temne are one of the largest ethnic groups in Sierra Leone and live close to the Fula’s origins in Guinea and their settlements along the coast of Sierra Leone. Since many diviners travel to perform divination, it is likely they have shared information and practices with the Fula.

Initiatory Dream of a Diviner

Most accounts of initiation from Temne diviners recount a dream with an ancestor, spirit, or both – without this dream, any attempts at divination would be unsuccessful. The power of divination is often passed down in a family by the transfer of a patron spirit. This patron spirit is often white and is usually a woman. After this dream, a sacrifice of a sheep or gold and other riches is usually required to seal the deal with the spirit. The patron spirit of many diviners will send them a sickness or mental illness that can only be healed if they accept divinatory powers.

“Fulani Divination Horn,” Barakat Gallery Store, The Barakat Collection.

Status of Diviner

Within the Temne culture, there are a few different denominations of diviners. Male diviners often rank above female diviners, and Muslim healers rank above traditional herbalists. Most diviners cannot support themselves with divination alone, but the most famous diviners can grow wealthy and gain status from their work. A local diviner often is not well-respected because there is no novelty; many villagers assume they already know their business and inform their predictions from gossip. Since diviners are supposed to channel the unknown power of spirits and not local talk, they gain credibility from an outsider status.

Visits from Women

Men often call on diviners for public ceremonies, such as the exposure of witchcraft, but women are far more likely to meet with diviners more often and in private. Their most common requests are love or family-focused – often involving love potions, remedies for barrenness, help for sick children, or retribution against an adulterous husband. Oftentimes, women are blamed for familial problems and are more likely to try to intervene with the help of a diviner.

Common Practices

Herbalism

Many diviners are well-versed in the ways of herbalism, which they use for both healing and casting spells. Diviners can use herbalism to practice both good and bad medicine, depending what their client asks for. This medicine can cast love spells, death spells, help political campaigns, and more. A Sierra Leonean newspaper speaks of the power of herbalism,

"The native doctor by the power of simple leaves is even able to make a love hypnotism of which the charm prepared forces the other partner subject to his demands and love him or her almost in the superlative…It is even believed that with this magic, strings are turned into deadly pythons against enemies more so to cause thunderbolts…On the contrary, however, we find the native doctor quite indispensable in certain ailments. He becomes the healing agent. There are often serious cases treated by the native doctors which become a medical dilemma with our modern physicians."8

The herbalist skills of diviners are both feared and respected. Their natural remedies for illness are often relied upon for medical help, particularly when a modern physician is not available. On the other hand, their ability to create a love potion and destructive spells are feared.Herbalists are also known to create charms and other defenses against witchcraft, protecting the people and crops of their villages.9

Mechanical Techniques

Many common forms of divination use mechanical techniques – which could involve the casting of pebbles or cowrie shells, writing on a Quranic slate, counting Islamic rosary beads, and more. The oldest and best-known form of divination is called an-bère, or the casting of river pebbles. A diviner will ask a question to the spirits, and then will hold 30-60 pebbles in his hands and cast them on a mat. He will then pick up a handful of the stones and transfer them between his hands while saying a Muslim prayer, and place the stones back on the mat in a circle formation. He counts the pebbles in pairs as he lays them down, and the remaining one or two pebbles are placed in the center. A single pebble in the center is indicative of the desired answer, while two pebbles indicate an undesired answer.10 These pebbles can be cast and recast to narrow down the answer with further questioning.

When a sufficient answer is received for the first question, the diviner will go on to arrange pebbles in four columns which can convey more complicated messages.11 Each row will have its own meaning and can indicate many things, including death, whether a sacrifice was deemed acceptable by the spirits, possible political promotion, and more. Diviners do not follow particularly strict rules of large-scale pattern, but rather draw imaginative connections between small groupings of stones and make an interpretation.

Dreams and Omens

In the Temne culture, when a person dreams they are thought to enter an entirely different world, ro-mà-rè. Ro-mà-rè falls somewhere between the mortal world and that of spirits and witches, ro-seròn. In ro-mà-rè, a person can communicate with these spirits and witches along with the dead. Dreams are thought to be a place where a person can attain truth unavailable in the human world, but also a place of danger where one can be converted to witchcraft. If a dream is thought to be important, a diviner is often consulted to discern its meaning.

“Amulet,” National Portrait Gallery, 13 Feb. 2002.

Omens found in the waking world also hold significance to the Temne. An omen could predict good fortune, negative talk, a successful journey, or even death. A strong importance was placed on the binary of left and right; with the right signifying success and the left signifying failure. Many omens are born out of this binary; for example, a stubbed toe on the right foot is an omen of a successful journey to come, while if you stub the left, you might as well turn around. One of the most terrible omens is to witness something out of the ordinary, "As a general principle of interpretation of events, one of my informants laid down that if you see what is 'very hard to see' – i.e. an unusual sight – you are going to die."12 These unusual sights could include nocturnal animals in the daytime, a bush animal in the village, and other abnormalities. To witness something strange signifies that the viewer is no longer within the ordinary human experience and precipitates death.13 A diviner is often heavily relied upon to interpret the specific meaning of omens, particularly in the case of a strange event.

Connections to Russel

Looking for similarities between Russel’s book and the ideas and techniques of the Temne diviners could reveal a stronger connection between Russel and Sierra Leone. If Russel authored her book, it was likely informed by European techniques of divination she witnessed in her teenage years and adulthood, but it also may have carried some vestiges of divination techniques from her birthplace.

Russel’s Initiatory Dream

Starting with Russel’s narrative, I found Russel’s explanation of how she received her divination powers to be very similar to the Temne initiation of a diviner. Russel said,

I began again to premeditate the destruction of my life, and again fixed upon a when the spirit of my father again appeared to me the night previous accompanied by another bright spirit, clad in purple, who touching me with something it carried in his hand, thus addressed me – “young woman, stay thy hand and raise it not against thy own life, for thy afflictions shall shortly cease – thy unjust punishments has enkindled the wrath of the Most High, who has commissioned me to unrivet they chains, and to vest the [thee] with power to foretell rema events, and prophecy things that shall surely come to pass, whereby thou shalt soon gain thy freedom, and be ranked among the most extraordinary of thy fellow-creatures – whatsoever thou shalt hereafter dream, that mind ye and prophecy, and it shall come to pass. I also vest thee with power to interpret dreams of others, and by signs, moles and tokens, to foretell the most remarkable events of lives!” – upon saying this the bright spirit vanished – upon which the spirit of my father said to me – “my daughter be comforted, for the spirits of thy mother and brother dwell with me!”14

Russel’s dream aligns with many aspects of the Temne divination dream. Her father appears in a dream with a spirit who vests her with divinatory powers, just as an ancestor will appear to a Temne diviner with a patron spirit. Since divination was a relatively common profession for the Fula people, Russel’s father could have been a diviner himself. One Temne diviner recounts his patron spirit using a “red cloth with perfume in it” to give him divinatory sight, just as Russel describes the spirit “touching me with something it carried in his hand”.15 We can also focus upon the “his” possessive here, which indicates that the spirit was masculine. In Temne culture, the patron spirit must be the opposite sex of the diviner, or else the diviner may lose his mind. Russel was also contemplating suicide before the spirit appeared, and the spirit tells her not to take her life because her “afflictions shall shortly cease”. A diviner often experienced sickness or mental illness before he had his initiatory dream, which would then be healed when he assumed divinatory powers. Russel did not wish to commit suicide after her initiatory dream, and she used her divinatory powers to help a man who purchased her freedom. If Russel’s enslavement was the “affliction” the spirit referred to, we can draw a parallel between the way Temne diviners healed their illnesses with divination and the way Russel was able to find freedom from enslavement.

Russel’s Divination Techniques

Love Charms

Russel includes two different love charms in her book for men and women, titled “Directions to young ladies how to obtain husbands they most desire” and “Directions to young gentlemen how they may obtain the wife they most desire.”16 The love charm for women to use consists of bunches of flowers, cherries, or roses depending upon the birth season of the desired man, which must be soaked in the bathing water of the woman and worn close to the body by both the man and woman for three days. The woman then must dry the bunches and keep them in her clothing chest, and "you must contrive to stand or pass within six feet of the young man, who from that moment (if he has worn or even smelt of the flowers that you sent him) contracts that love and regard for you which your presence will ever after rather tend to crease than to diminish."17

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book

These instructions are mostly the same for men, who must also add musk and cinnamon. These love charms are reminiscent of the herbalist techniques that Temne diviners use. . The way in which Russel pays attention to the lover’s time of birth is also reminiscent of Temne tradition, which attends to time and season in regards to ceremony or herbalism. The Temne tend to make sacrifices at harvest-time, collect plants for healing medicine during the day and harmful medicine at night, and create their most effective medicine at “full moon time in the height of the dry season.”18 It is possible that Russel drew some aspects of her love potions from distant memories of the Temne diviners in her youth.

Dream Interpretation

Russel includes a long list of symbols found in dreams and their potential predictive meaning for the dreamer. For example, she says “Bridge – To dream you are going over a bridge without difficulty, is a sign of prosperity.”19 These symbols themselves do not seem to have a connection to Temne culture, but the emphasis on the importance of dreams is similar. A Temne diviner is often consulted to interpret the meaning of dreams, and Russel makes this sort of diviner consultation accessible with the publication of her book.

Russel says,"the greatest and most important object of such dreams, as ghosts, apparitions, spectres, and such things, is, that they shew the brain to be at that time in a state of derangement, and the stomach disordered; they shew disappointment in courtship, and that the person you love, hates you."20

The most important figures of Temne dreams are certainly ghosts of ancestors and spirits, although they do not interpret their presence the same way as Russel. A Temne person believes that these ghosts and spirits are real and that a dream is an opportunity to receive predictions for the future. While Russel does not seem to indicate an avenue of communication with ghosts and spirits, she does indicate that their presence is notable and can reveal important predictions for the future.

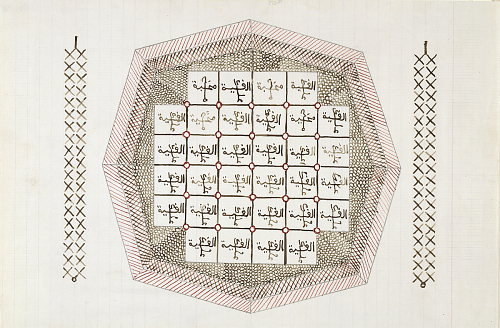

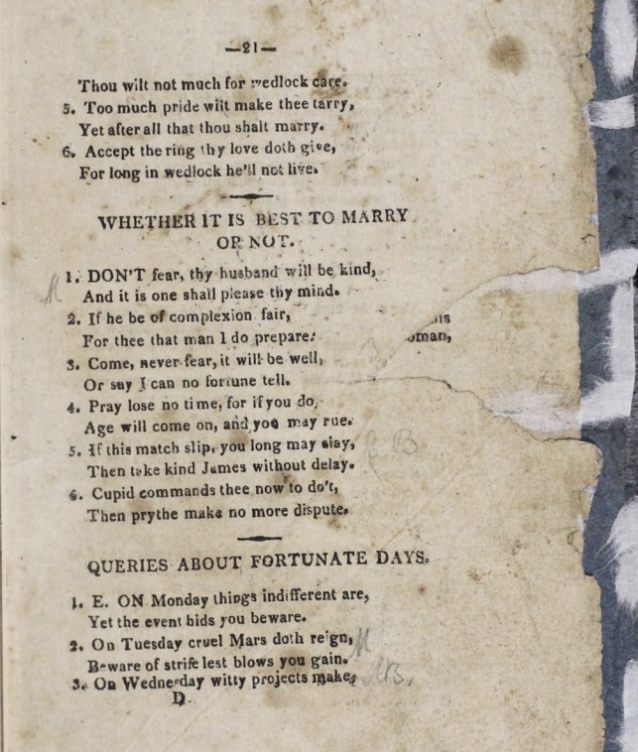

Russel’s Fortune Chart

Russel includes a fortune chart in her book that corresponds to questions and answers used to resolve “matters of love and business.”21 It is unclear how exactly she picked answers from this table, but she describes “pricking a figure in the following table.”22 This practice sounds similar to some of the mechanical techniques used by Temne diviners, such as “khatt ar-raml”, an Islamic form of divination. Khatt ar-raml "involves building up tetragrams from a series of single and paired marks made in the sand in a divination tray, forming patterns that are virtually identical [to] an-bère."23 The technique uses marks, usually dashes that can look like dots (similar to pin-pricks) to create Islamic squares, and was used in tandem with an Arabic divination manual called Khatt ar-raml. The Temne derived another method from khatt ar-raml called an-raməl, which involves using a pen to make dashes on an Arabic slate that form two curved lines. They then would count the dashes and look up the number in an Arabic divination manual, much like Russel would consult the answers to her chart in her book. The pattern formation Russel may have used with her pin-pricks is also somewhat reminiscent of an-bère, which created messages from rows and columns of cowrie shells.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book

The squares of Russel’s divination chart are also similar to Islamic “magic squares” used by Temne diviners. Magic squares consisted of a grid of squares that were supposed to link letters of the alphabet and numbers and to represent the cosmos. A middle square was often left blank to represent Allah’s place in the center of the universe, and the squares were referenced when making medicine or amulets. While Russel’s divination chart is used differently, she may have picked up the visual of the squares growing up in Sierra Leone. It is unlikely that Russel was taught any divinatory techniques as a child, but she may have witnessed those we mentioned above and combined the memory in her fortune-telling chart.

Conclusion

The information indicates that Russel’s authorship is more likely than Gardner may have thought. Russel could have been referring to the Fula people in Sierra Leone when she spoke of the “Fuller nation”, and her assertion of living three hundred miles southwest of Sierra Leone can be easily attributed to the haziness of childhood memories, a different system of distance measurement, and the pressure Black writers experienced to provide a detailed account of the facts of their life. Russel’s initiatory dream is also strikingly similar to the smallest details of a traditional Temne initiatory dream. The assumption of divinatory powers results in her freedom from enslavement on the brink of her own mental exhaustion and suicide, somewhat like the Temne description of healing a terrible illness after assuming their powers.While the other techniques in Russel’s book do not hold a strong connection with Temne divinatory techniques, this was likely because she was only nine when she was forced into enslaved. Even if she did remember some of these techniques of divination, there were likely more popular forms of divination in Boston she would have felt compelled to stick to. While the information about Sierra Leonean divination does not prove Russel’s authorship, it leans in that direction because it is unlikely that a publisher could have fabricated an initiatory dream so similar to that of the Temne, and that he would have known of the Fula people, who were a minority in Sierra Leone.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book.

As an adult, Russel was already unusual in her independence as a free, unmarried Black woman, supporting herself and her children. Her position as a fortune-teller and an author makes her a truly remarkable figure of the nineteenth-century United States. As an enslaved woman, Russel revisited the memory of divination she likely had from her childhood in Sierra Leone. She had the idea to monetize this memory in a brand-new setting, managing to leverage her reputation as a diviner to free her from slavery. Divination continued to bring her fortune and success throughout her entire life, as she bought property in Boston and supported a family on the wages she earned from fortune-telling. Russel entirely subverted the role of the enslaved Sierra Leonean witch with her success as a fortune-teller. While the idea of magical practices for many Black women was a path to enslavement, Russel used magic as the catalyst for her freedom.

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 269

- Jalloh, Alusine. “Muslim Fula Business Elites and Politics in Sierra Leone.” African Economic History, no. 35 (2007) 91-92

- Shaw, Rosalind. Request for Interview, (2020).

- Shaw, Rosalind. Request for Interview, (2020).

- Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” American Ethnologist, vol. 24, no. 4 (1997) 864

- Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” American Ethnologist, vol. 24, no. 4 (1997) 865

- Ibid

- Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, (1982) 94

- Basu, Paul. “Fieldnotes: Protection from Witchcraft.” [Re:]Entanglements (2019).

- Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, (1982) 122

- Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, (1982) 127

- Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, (1982) 141

- Ibid

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 272

- Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, (1982) 86

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 275

- Ibid

- Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, (1982) 95

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 277

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 277

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 286

- Ibid

- Shaw, Rosalind. Memories of the Slave Trade: Ritual and the Historical Imagination in Sierra Leone. University of Chicago Press (2002), 86).

Bibliography

“Amulet.” National Portrait Gallery, 13 Feb. 2002, npg.si.edu/object/nmafa_2003-13-2.

Basu, Paul. “Fieldnotes: Protection from Witchcraft.” [Re:]Entanglements, 21 Mar. 2019,

re-entanglements.net/protection-from-witchcraft/.

Cole, Ngozi. “The Real Meaning Behind Sierra Leone's Beautiful Name.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip, 3 Sept. 2018, theculturetrip.com/africa/sierra-leone/articles/the-real-meaning-behind-sierra-leones-beautiful

Crompton, Greg, director. Witches in Sierra Leone. YouTube, Journalists for Human Rights, 14 July 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=WU9nhVW8zDk.

“Divination Bowl.” British Museum. http://www.sierraleoneheritage.org/item/BM%3AAf.1909.805.1/divination-bowl.

“Fouta Djallon.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fouta_Djallon.

“Fulani Divination Horn.” Barakat Gallery Store, The Barakat Collection, www.barakatgallery.com/store/index.cfm/FuseAction

Gardner, Eric. "'The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book': An Antebellum Text 'By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.'" The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, ( 2005): 259-288.

Journalists for Human Rights, dir. 2009. Witches in Sierra Leone. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WU9nhVW8zDk.

“Map of Sierra Leone.” World Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/sierra-leone

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book

Shaw, Rosalind. Request for Interview, 15 Dec. 2020.

Shaw, Rosalind. “Temne Divination: The Management of Secrecy and Revelation.” University of London, 1982.

Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” American Ethnologist, vol. 24, no. 4, 1997, pp. 856–876. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/646812.

Shaw, Rosalind. Memories of the Slave Trade: Ritual and the Historical Imagination in Sierra Leone. University of Chicago Press, 2002.

“Slaves packed below and on deck.” 1857. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-1bee-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99