Created by Juliet Tomasuolo

Introduction

In order for a nineteenth century text to qualify as feminist, the text must display (at some points) that men and women are created equally. In doing so, the text needs to acknowledge that men and women are entitled to the same life experiences, and neither sex is inferior to the other. Russell’s text fits this definition as it is consistently inclusive of both men and women as well as avoids suggesting that only one sex is made to read this dream book.This scholarly edition provides a feminist reading of Chloe Russell’s Fortune Teller Dream book. Russell’s text is engaging with feminism in relation to the time period Russel was writing in grappling with both the strengths and limitations of the text.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

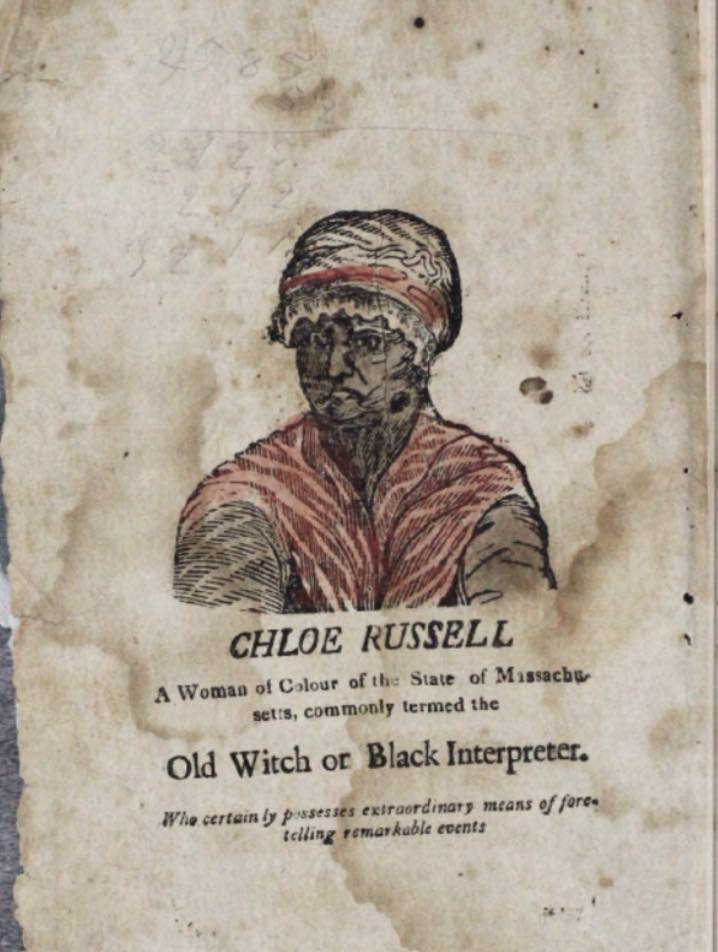

Russell’s Book Cover

The language Russell employs throughout this cover page is inclusive of both men and women. For example, she introduces the book as something that “every person” can use to find out information about important life events. Russell not only has marriage instructions for just women, but men as well. During this time period, women were expected to get married, provide a nice home life for their husband, and have children. If a woman was not married, she was seen often othered and assumed to be regarded as a different class in society. Russell’s decision to also include directions for men on getting married lessens the burden on women of traditional societal roles. The “Directions for Young Ladies” text appears larger and on top of the “and for Young Gentlemen” text.1 Under a feminist lens, it can be argued that Russell was paying homage to her fellow women. Since “Young Ladies” appears in bigger text and before “Young Gentleman,” Russell places more emphasis on women and their rights to choose their own husband.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

Lastly, it is important to note how Russell signs her name. She specifically chooses to identify herself as “A Woman of Coluor.”2 This is crucial to the reading of the text because it ties into the introduction, where she informs the reader of her life experiences. This introduction shares parallels to a slave narrative, and empowers Russell’s identity as she is taking claim over her identity as a “poor unfortunate Female African” and making them her own words.3

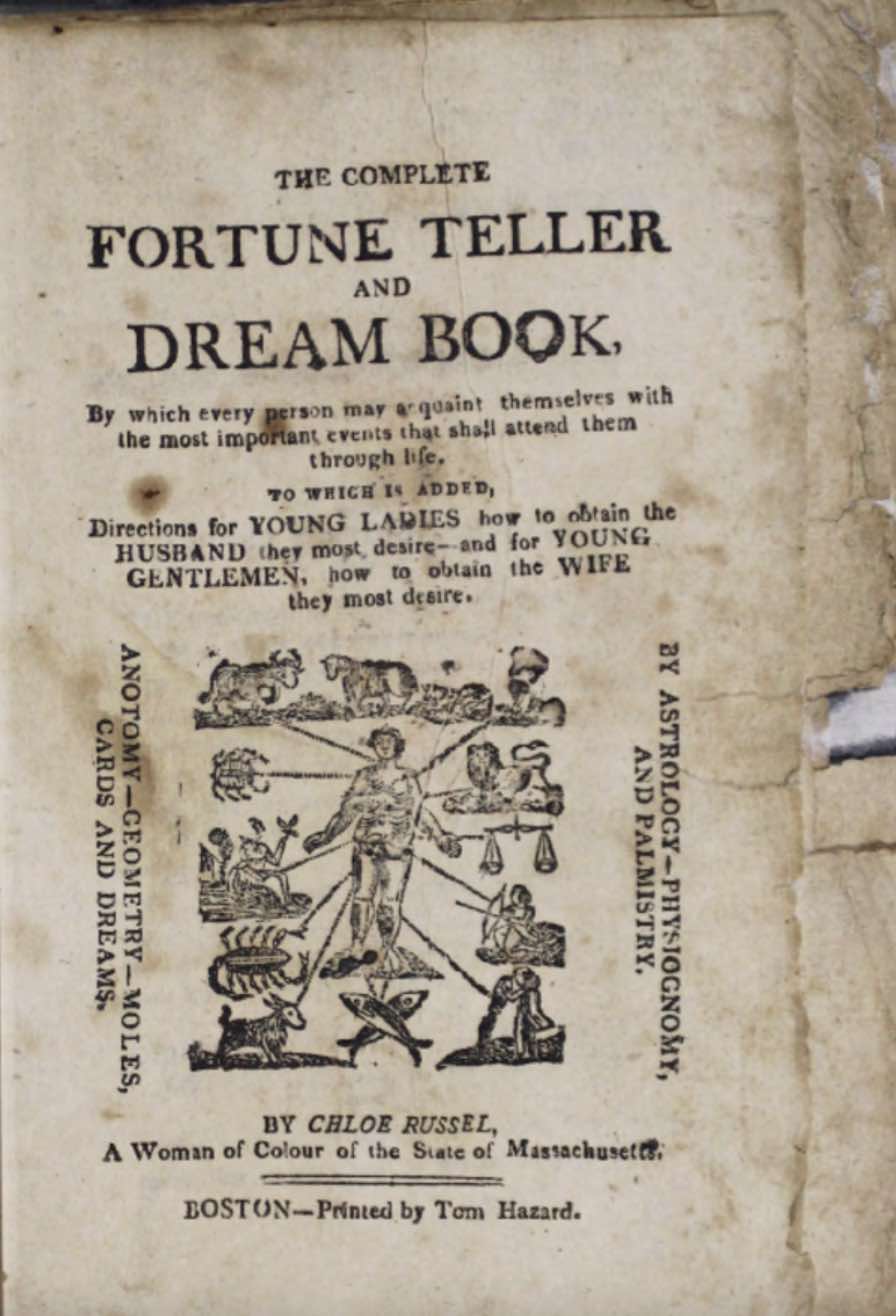

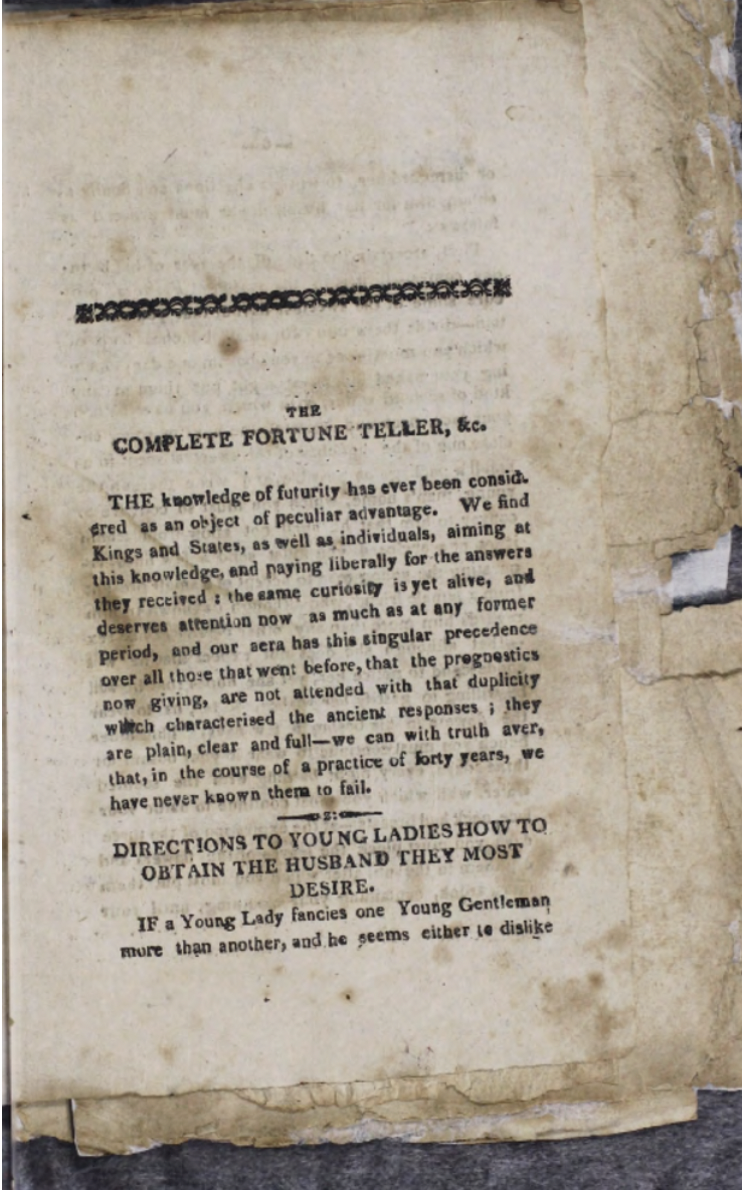

Feminist Diction

There are two words featured in the “Directions to young ladies how to obtain husbands they most desire” portion of the book that stand out the most: “obtain” and “if.”4 It can be argued that these words work to promote equality between the two sexes. More specifically, the word “obtain” is used to describe getting married to a man; and the same language is used in the men’s portion. What’s so interesting about this word choice is that it is objectifying both men and women, as it implies that ownership is being taken over that person. For a woman to be taking ownership in obtaining a husband places the woman in charge of the man. This language is again seen when talking about men obtaining a wife, which becomes more problematic. Russell’s choice to mirror this language when discussing men finding wives can be seen as setting back the progress she has made in this text being a feminist one. However, it can also be argued that it is truly feminist, for Russell is objectifying both sexes, placing them on an even playing field.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

The word “if” holds a lot of value because it heavily implies choice. To clarify by writing “If a young lady fancies,” Russell is asserting an opinion that women have the choice to get married or not, and to whoever they fancy.5 During this time period, it was often that women were married off by their families without too much say in it. Russell illustrates that women have some level of authority when it comes to their marital status.On the contrary, Russell is not advocating much for the rights of domestic servants or widows. This heavily plays into the concept of Intersectional Feminism as it appears that she is arguing for the young ladies’ and wives’ equality, but not necessarily every type of woman. Although much of the attention is on the women-to-be-wed, maids and widows are considered in her sections “What kind of a husband a widow or maid shall have” and “Whether a maid shall have him she loves.”6 The problem with these two sections is that they can be seen as insisting that maids and widows ought to be married since there is no version of these sections offered for men. However, one can argue the stronger case that these sections work towards a more inclusive type of feminist text by Russell, but are not entirely there yet. Based on the rest of the book, Russell is still meeting the definition of feminism offered above by nineteenth century standards.

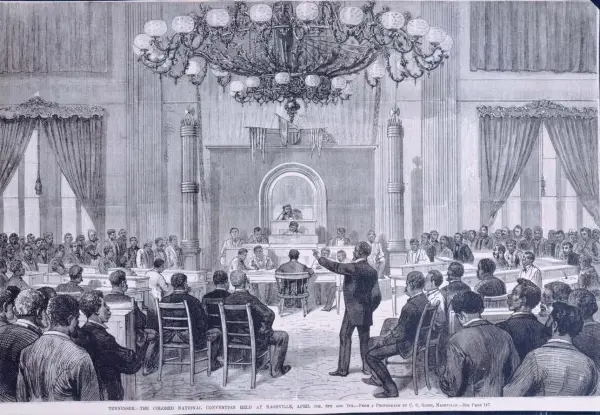

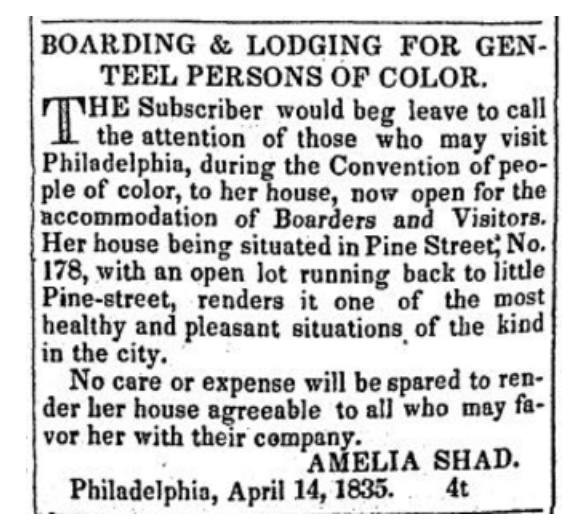

Amelia Shad’s Boarding House Advertisement

From 1830-1835, the Colored Conventions took place in boarding houses in Philadelphia.7 While these conventions were not in Massachusetts working alongside Russell, they too served as a vehicle to promote racial justice and Feminism. Boarding houses were not exclusive to Philadelphia and were often led by women who were entirely in charge of the house, and therefore became the breadwinners. However, the women who ran the boarding houses did not always have a husband by their side. In Los Angeles in 1900, older Black women who were often widowed or divorced ran boarding houses; they rented out their extra rooms to boarders, usually “new Black migrants to the city.”8 Comparatively, these boarding houses helped to support women who were barely making ends meet as domestic workers. Since boarding houses were much more affordable, they became necessary to the survival of many Black women and men.9

Leslie, Frank, “National Colored Convention, Nashville, 1876,” March 1876, Worcester, Massachusetts, American Antiquarian Society, Newspaper.

The image on the left features an advertisement made by Amelia Shad, sole owner of a boarding house.10 A key aspect of this advertisement is that Amelia Shad is running this boarding house herself as a widowed woman. While in present day widows are not seen as a lesser class in society, they were in the nineteenth century, especially female widowers. Finding work as a Black female was hard enough, but not having your spouse around to support you anymore is extremely challenging. For Amelia to own a boarding house is a major accomplishment itself, but she is also providing Black widows with affordable housing, looking past their gender and marital status.

“Boarding and Lodging for Genteel Persons of Color,” 14 April 1835, The Liberator, Newspaper.

This ties back to Russell because these conventions and boarding houses occurred around the same time that Russell’s book was circulating around Massachusetts. While Russell was not the original feminist, she was asserting these ideas in text while other women were asserting them in-person. However, advertisements such as these are more considerate of all types of women, while Russell is mainly considering women to be wed.

A Woman’s Role in Society

These pictures are reminiscent of the time period as there is a shift in how women take part in society. The wedding dress is rare for the time period, as brides wore colored dresses until the late nineteenth century (“Dress, Wedding”).11 This dress is symbolic because it illustrates what is expected of a woman: marriage and children. It is contrasted by the newspaper article discussing the various causes for divorce as it says, “when a woman has endured till she can endure no longer.”12 This is not only relevant to this time period, but also present day; society has made marriage the most important event in a woman’s life. Women are given the unfair expectation of having a family as if it is their only purpose.

“Morning dress,” 1820, Image.

It can be further noted that throughout the fortune telling parts of the book, Russell uses the pronoun “you” to address the reader directly as a person and not as their gender. This means that Russell is not solely discussing marriage in terms of solely women, but men too; she is suggesting that a marriage is made of two equally valued partners, not one man leading it.

“Marriage, DiVorce and Men and Women as seen through the Eyes of the Law and Society: Causes of the Many Divorce Suits Reported from Atlanta Courts Last Week and Diverse Views Given. Why Marriage does Not Succeed. Story of a Man Who Seeks to Legalize His Marriage with His Daughterin-Law–the Week in Woman’s World–Topics for Women and Society,” Oct 24 1897, The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945).

Rise of Women

Russell’s text is existing in the same century as the start of various feminist movements across the country and all are linked. During the 1890s to the 1950s, Black women historians rose in their field, facing various obstacles blocking their path to success.13 This is a niche field to be discussing, but accurately reflects both the world that Russell lived in and present day. Black women, like Chloe Russell, are significantly disadvantaged compared to their white counterparts. The pathway for Black women has always been more difficult than that of white women, but also than that of Black men. Often, when Black history is taught, men are the faces of many struggles, movements and it’s crucial that Black women are given that same platform to speak their truths, as they have contributed greatly to calling for action against racism.

McQuillar, Tayannah Lee, and Katelan V. Foisy, The Hoodoo Tarot: 78-Card Deck and Book for Rootworkers, 2020, Rochester, Vermont, Book.

Russell’s text is attempting to give women more of a voice, and demonstrate that women do, in fact, have free will. Russell also states on the cover of her book that she is a woman of color; it may have been that white men and women were purchasing her book, but it can be argued that Russell is speaking as a Black author to a Black audience. It is clear that Russell is attempting to empower women through discussing marriage in terms of free will to choose whichever suitor, and in trying to include maids and widows. Whether or not Russell’s text is genuinely inclusive of all types of women is up for debate, but does not impact the fact that the text satisfies the simple definition offered for what qualifies as a feminist text.

Endnotes

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 259-28

- Ibid

- Ibid 269

- Ibid 275

- Ibid 275

- Ibid 287

- De Vera, Samantha, “Cover,” Black Women’s Economic Power: Visualizing Domestic Spaces in the 1830s, ed. P. Gabrielle Foreman and Sarah Patterson (The Colored Conventions Project) coloredconventions.org/women-economic-power/.

- Campbell, Marne L“African American Women, Wealth Accumulation, and Social Welfare Activism in 19th-century Los Angeles.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 97, no. 4, (2012) 381

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- “Marriage, DiVorce and Men and Women as seen through the Eyes of the Law and Society: Causes of the Many Divorce Suits Reported from Atlanta Courts Last Week and Diverse Views Given. Why Marriage does Not Succeed. Story of a Man Who Seeks to Legalize His Marriage with His Daughterin-Law–the Week in Woman’s World–Topics for Women and Society.” The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), (1897) 14

- Dagbovie, Pero Gaglo, “Black Women Historians from the Late 19th Century to the Dawning of the Civil Rights Movement,” The Journal of African American History, vol. 89, no. 3 (2004) 241.

Bibliography

Dagbovie, Pero Gaglo. “Black Women Historians from the Late 19th Century to the Dawning of the Civil Rights Movement.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 89, no. 3, 2004, pp. 241–261. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4134077. Accessed 9 Dec. 2020.

De Vera, Samantha. “Cover.” Edited by P. Gabrielle Foreman and Sarah Patterson, Black Women’s Economic Power: Visualizing Domestic Spaces in the 1830s, The Colored Conventions Project coloredconventions.org/women-economic-power/.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005, pp. 259–288. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30045526.

Marne L. Campbell. “African American Women, Wealth Accumulation, and Social Welfare Activism in 19th-century Los Angeles.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 97, no. 4, 2012, pp. 376–400. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5323/jafriamerhist.97.4.0376.

“Marriage, DiVorce and Men and Women as seen through the Eyes of the Law and Society.: Causes of the Many Divorce Suits Reported from Atlanta Courts Last Week and Diverse Views Given. Why Marriage does Not Succeed. Story of a Man Who Seeks to Legalize His Marriage with His Daughterin-Law–the Week in Woman’s World–Topics for Women and Society.” The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), Oct 24 1897, p. 14. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.neu.edu/cv_676894/docview/495412242/fulltextPDF/97ABF544AA4144C3PQ/8?accountid=12826.

“Morning dress.” 1820. Image. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/108027