Created by Brendy Jerome

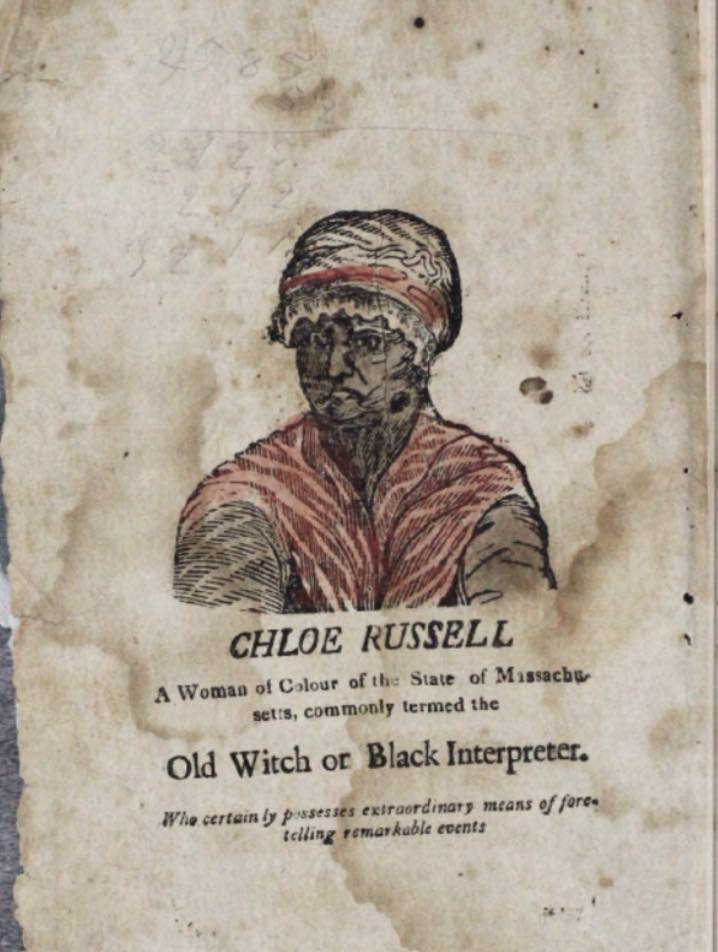

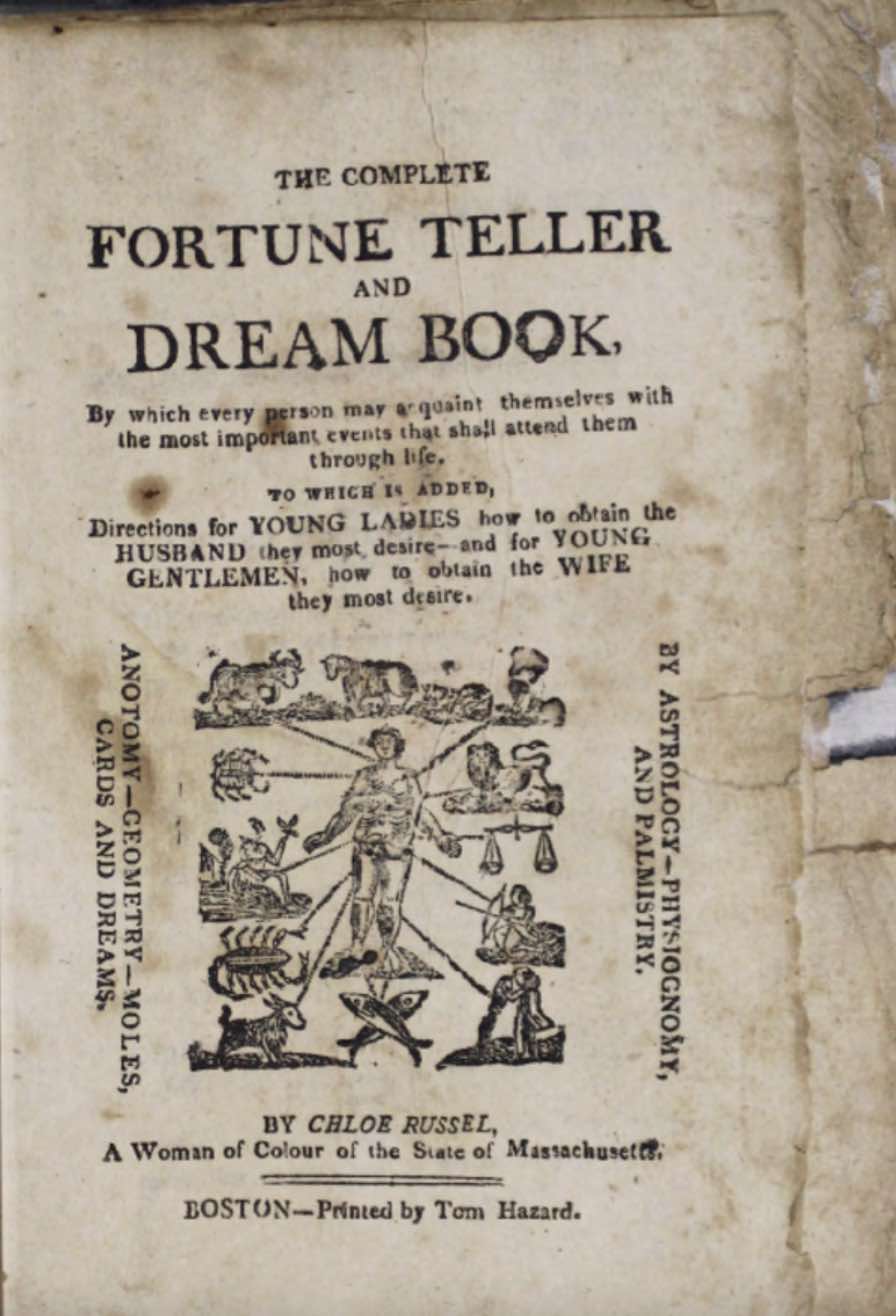

The existence of Chloe Russell’s Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book demonstrates an early American fascination with the mysticism of Africans and African Americans. The prevalence of Euro-centric narratives in American history has skewed popular opinion into thinking the transatlantic slave trade only gave European culture to Africa when the reality was more similar to a quid pro quo. Below we will explore three religions, African traditional religions (ATRs), Islam, and Christianity that were prominent in Africa and that Russell would have encountered living both in Sierra Leone and the United States.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

The Spirit

ATRs are often focused around soul-like life forces or a spiritual energy that exists in all things. Scholars have called this belief animism or animatism, but practitioners of ATRs have felt these terms coined by colonizers were vague and overreaching.1 In Sierra Leone and most of West Africa, this life force would have been called Nyama “Nyama is often conceived of as impersonal, unconscious energy, found in men, animals, gods, nature and things. Nyama is not the outward appearance, but the inner essence” Geoffrey Parrinder writes.2 It is this central belief that outlines and guides spiritual other practices.

Seven, Seven Twin,“Shango (Yoruba orisha) and his Festival,” Image.

God and gods

Like in Islam or Christianity, there is a belief in a God-like creator figure often referred to as the Supreme Being or Supreme Divinity and often represented with a triangle. In the triangle a man resides at the earthly base while the Supreme Being is at the top or the metaphorical sky. Along the sides of the triangle are ancestors and other divinities, who allows communication from man to the Supreme Divinity.3

“African Pantheons and the Orishas: Crash Course World Mythology #11.” 12 May 2017, Crash Course. YouTube.

The Yoruba of Western Africa has a pantheon of 401 divinities used to mediate communication between humans and the Supreme Divinity called orisha. These gods were highly tied to nature; male deities were often associated with the heavenly sky while female deities were associated with the land. Each gods not only had roles as messengers but were also creators themselves, believed to be working with or for the Supreme Being.

Ancestor Worship

Another motif in traditional religions are ancestral worship in which important elderly or deceased figures are honored and appealed to. These ancestors reflect the spiritual net that communities exist in. The nyama in ancestors does not die and therefore nor do these people. Rather, they move from different forms of existence, life and death.4

Ancestors were appealed to for a multitude of reasons, both good and bad. Blame was often placed on ancestors for misfortunes like infertility, draughts, and illnesses for which sacrifices were made.5 Ancestors also frequented dreams which not only reflected the constant connection and interest between the dead and the living, but also were used for fortune telling and to prevent future harm.

“Ancestors, Spirits and God,” 2017, History of Africa with Zeinab Badawi, Hosted by Zeinab Badawi, BBC.

Structure

West African traditional religions were marked by temples where gods were worshiped. More commonly, priests would not be confined to these temples but were universally considered servants to a god.

As mentioned above, mediums were also crucial to the functioning of these religions. Mediums were often women were considered to be possessed by an ancestor or god.Diviners were also crucial to problem solving in communities and would even diagnose diseases. These medicine-men or nganga were struck by inspirations that helped to choose the correct medicines for treatments.

“Ancestors, Spirits and God,” 2017, History of Africa with Zeinab Badawi, Hosted by Zeinab Badawi, BBC.

Islam

Africa has a strong presence of all Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The later two have a stronger presence in West Africaand spread primarily from North Africa. The conversion of communities to Islam was associated with political submission of Africans to the Arabs.6 Due to the importance of traditional religions in societal structure, Islamic law was slow to permeate in Western Africa. As Muslim trade increased, the religion proliferated Islamic traditions.7 Still, spiritualism clashed in West Africa.

Sufism

Islam brought to West Africa its own form of mysticism, Sufism to West Africa. Sufi brotherhoods follow the Sufi Way, which focuses on the wird, a prayer ritual for transmitting mystical knowledge. Sufism is highly organized and structured due to the formation of scholarly lineages. Economic and political power was associated with these structures and encouraged the spread of Sufism throughout West Africa.

The concept of nyama could be seen to be translated into baraka and then wilaya, a "friendship with God." Like traditional religion, good events stemming from wilaya were attributed to the person's relation to ancestors.8

The spread of sufism in Africa is attributed to the familial nature of the Brotherhood but was aided by the spread of prayer amulets and healing.

Said, Mahmoud, “The Whirling Dervishes,” 1929, Oil on Panel.

Amulets and Islamic Healing

Early African Islam supported Traditionalist beliefs that illnesses and diseases were caused by spiritual issues and offered Muslim prayer and amulets as alternative therapies to traditional methods. The success of Islamic practices over traditional ones did not conflict with Traditionalist ideology. Instead, it was thought that the Supreme Being was favoring the Muslim healers for their superior closeness to nyama. The amulets were called khatim and a modern day one can be seen to the left.9

Early African Christianity

Like Islam, Christianity spread to West Africa through the north. The proliferation began with the Roman colonization and conquest along the Mediterranean coast. Against popular belief, African Christians thus did not come to be during the slave trade but began much earlier. In fact, many prominent Christians balanced their religious identity with their cultural African identity. A significant figure was Saint Augustine of the African city Hippo, whose Berber heritage was criticized by his contemporaries but which he himself celebrated:

As an African man, writing to Africans, and even as one abiding in Africa, you could not have forgotten yourself and thought of Punic names as flawed…. Should this language be disapproved by you, you must deny that in Punic books produced by very educated men many wise teachings have been recorded; you must regret that you were born here, for this land is the still-warm cradle of the Punic language itself…. You disrespect and snub Punic names to such an extent, it is as if you had surrendered to the Roman altars.10

Augustine, though a baptized Christian was no less proud of his African status, demonstrating an early African and Christian identity forming.The colonization of Africa in the 16th century by European countries such as Portugal encouraged the spread of Christianity from North Africa.11 While many colonists focused on trade and economic gain, many also felt missionary duty and encouraged baptism of African rulers. This was especially common in Sierra Leone, where Russell was born.

Christianization of Enslaved Africans

Those people brought to the American colonies were mostly of pagan origin. Slave owners initially were reluctant to baptize their slaves as arguments had been made that it would be moral cause for enslaved people to be liberated.The traditional celebrations and religious practices of Africans in the American colonies were often suppressed in order to prevent cultural connection and to maintain power over enslaved people.12 Still, many masters allowed for enslaved people to participate in evangelical meetings and encourage conversion to Christianity due to a belief that it would encourage obedience.

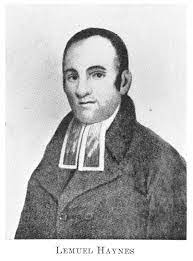

Lemuel Haynes: Christian Arguments Against Slavery

The existence of slave-holding Christians was a moral oxymoron. To appease the hypocrites' conscience, a few arguments were presented to show Biblical approval of the institution of slavery. However, upon the Christian education of enslaved people, many were able to dismantle these arguments. Lemuel Haynes' speech "Liberty Further Extended: Or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-keeping" is exemplar of the Christian rebuttals made to the hypocritical slaveowners. For example, in response to the argument that Africans are the descendants of Canaan and therefore doomed to slavery, Haynes noted that God declared that the curse on those of Canaan would not be passed down.13 The Christianization of Africans in America also encouraged their education and sense of identity and liberty.

"Rev. Lemuel Haynes," New York Public Library Digital Collections, Image.

The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book

As noted above, the work attributed to Russell is notable for its demonstration of American interest in African culture. We would like to look at a passage from Russell to analyze for the influence of the religions discussed above:

This singular dream made such a deep impression upon my mind, as to deter me from committing suicide the succeeding day, but as many months passed with seeing any chance of gaining my liberty, I began again to premeditate the destruction of my life, and again fixed upon a day-when the spirit of my father again appeared to me the night previous, accompanied by another bright spirit, clad in purple, who touching me with something it carried in his hand, thus addressed me-"young woman, stay thy hand and raise it not against thy own life, for thy afflictions shall shortly cease-thy unjust punishments has enkindled the wrath of the Most High, who has commissioned me to unrivet they chains, and to vest the [thee] with power to foretell remarkable events, and prophecy things that shall surely come to pass, whereby thou shalt soon gain thy freedom, and be ranked among the most extraordinary of thy fellow-creatures-whatsoever thou shalt hereafter dream, that mind ye and prophecy, and it shall come to pass. I also vest thee with power to interpret dreams of others, and by signs, moles and tokens, to foretell the most remarkable events of their lives!"-upon saying this the bright spirit vanished-upon which the spirit of my father said to me-"my daughter be comforted, for the spirits of thy mother and brother dwell with me!"14

This passage reflects a traditional event of the ancestor entering a dream. Russell's father appears to inform her of her future, but also to chastise her for her intended suicide, demonstrating the omnipresence and interest that ancestors take in traditional African religions. In addition, this ancestor imbues her with power "to interpret dreams of others" which is similar to the possession by ancestors that happens to mediums and priests. The description of a man in purple may also be an ancestor or a god. Of the Orisha, the goddess of wind, storms, death, and rebirth, Oya, is associated with the color purple. The gods Obatala, or Oshala, and Sopona are both depicted carrying objects. While Obatala, the creator of human bodies, uses a sword as a walking stick, Shopona, the god of smallpox, carries a broom.15 Through the description of the "bright spirit" Russell could be evoking the rebirth of Oya with the agency over her own body given by Obalata. The color purple also has meaning in Islam and is thought to represent inspiration.16 Still, the reference to the "bright spirit" and the "Most High" are vague enough that they could be references to the Abrahamic God and Jesus Christ by Russell's Christian audience.

Russell's pamphlet also includes descriptions of rituals that are similar to the creation of Islamic amulets. To make a man love a woman, Russell writes the woman must:

[P]rocure some of the sweetest flavour that you can obtain-divide them into two small bunches, both of which you must wear in your bosom one day, touching your naked body-at night put them in any kind of scented water with which you have bathed your face, neck and breasts-the next morning enclose one of the bunches of the sweetest scent in as small a package as possible and write thereon the young man's name, which you must so contrive to convey to him, that he shall not know from whom it came-enclosed you must send a few lines ... The other bunch you must continue to wear in your bosom for three days, every night bathing with the scented water with which you must continue to bathe your face, neck and breasts-at the expiration of the three days you must pluck the leaves of the flowers and dry them in the sun, after which you must put them into a trunk containing your clothing, until your clothes become scented therewith-very soon after dressed in some of the clothes thus scented, you must contrive to stand or pass within six feet of the young man, who from that moment ... contracts that love and regard for you which your presence will ever after other tend to increase than to dim.

Both rituals require patience, bathing, inscription, and the giving of an artifact to someone else. The similarity of these processes reflect not only the integration of Islam into African culture but also shared values.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

Endnotes

-

- Parrinder, Geoffrey. African Traditional Religion. (Greenwood Press, 1970)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Westerland, David. African Indigenous Religions and Disease Causation. Brill Leiden, (2006)

- Parrinder, Geoffrey. African Traditional Religion. (Greenwood Press, 1970)

- Kalu, Ogbu U. “Ancestral Spirituality and Society in Africa.” African spirituality: forms, meanings, and expressions. Edited by Jacob K. Olupona, (New York: Crossroad, 2000)

- Kalu, Ogbu U. “Ancestral Spirituality and Society in Africa.” African spirituality: forms, meanings, and expressions. Edited by Jacob K. Olupona, (New York: Crossroad, 2000)

- Christelow, Allan. “Islamic Law in Africa.” The History of Islam in Africa. Edited by Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels. (Ohio University Press, 2000)

- Owusu-Ansah, David. “Prayer Amulets, and Healing.” (New York: Crossroad, 2000)

- Limba artist. Amulet. Paper, colored inks.( Sierra Leone: Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, D. C.)

- Thornton, John K. “On the Trail of Voodoo: African Christianity in Africa and the Americas.” (Cambridge University Press, 2018) 21-278.

- Thornton, John K. “On the Trail of Voodoo: African Christianity in Africa and the Americas.” (Cambridge University Press, 2018) 21-278.

- Haynes, Lemuel. “Liberty Further Extended: Or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-keeping.” (1776).

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 260

- Westerland, David. African Indigenous Religions and Disease Causation. Brill Leiden, (2006)

- Levtzion, Nehemia and Pouwels, Randall L. “Patterns of Islamization and Varieties of Religious Experience among Muslims of Africa.” The History of Islam in Africa. Edited by Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels. (Ohio University Press: 200

Bibliography

“African Pantheons and the Orishas: Crash Course World Mythology #11.” Crash Course. YouTube, 12 May 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J2se_zimj40

“Ancestors, Spirits and God.” History of Africa with Zeinab Badawi. Hosted by Zeinab Badawi, BBC, 2017. https://youtu.be/GlKSp2H0V0w

Christelow, Allan. “Islamic Law in Africa.” The History of Islam in Africa. Edited by Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels. Ohio University Press, 2000.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, June 2005, pp. 259-288.

Haynes, Lemuel. “Liberty Further Extended: Or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-keeping.” 1776.

Kalu, Ogbu U. “Ancestral Spirituality and Society in Africa.” African spirituality: forms, meanings, and expressions. Edited by Jacob K. Olupona, New York: Crossroad, 2000.

Levtzion, Nehemia and Pouwels, Randall L. “Patterns of Islamization and Varieties of Religious Experience among Muslims of Africa.” The History of Islam in Africa. Edited by Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels. Ohio University Press, 2000.

Owusu-Ansah, David. “Prayer Amulets, and Healing.” African spirituality: forms, meanings, and expressions. Edited by Jacob K. Olupona, New York: Crossroad, 2000.

Parrinder, Geoffrey. African Traditional Religion. Greenwood Press, 1970.

"Rev. Lemuel Haynes." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-de6e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book

Ryan, Patrick J., S.J. “African Muslim Spirituality: The Symbiotic Tradition in West Africa.” African spirituality: forms, meanings, and expressions. Edited by Jacob K. Olupona, New York: Crossroad, 2000.

Said, Mahmoud. “The Whirling Dervishes.” Oil on Panel. 1929.

Seven, Seven Twin.“Shango (Yoruba orisha) and his Festival.” Image. https://www.culturesofwestafrica.com/west-african-religion/

Thornton, John K. “On the Trail of Voodoo: African Christianity in Africa and the Americas.” The Americas, vol. 75, no. S1, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 21-278.

Westerland, David. African Indigenous Religions and Disease Causation. Brill Leiden, 2006.