Written and curated by Matt Yan and Savita Maharaj

Introduction

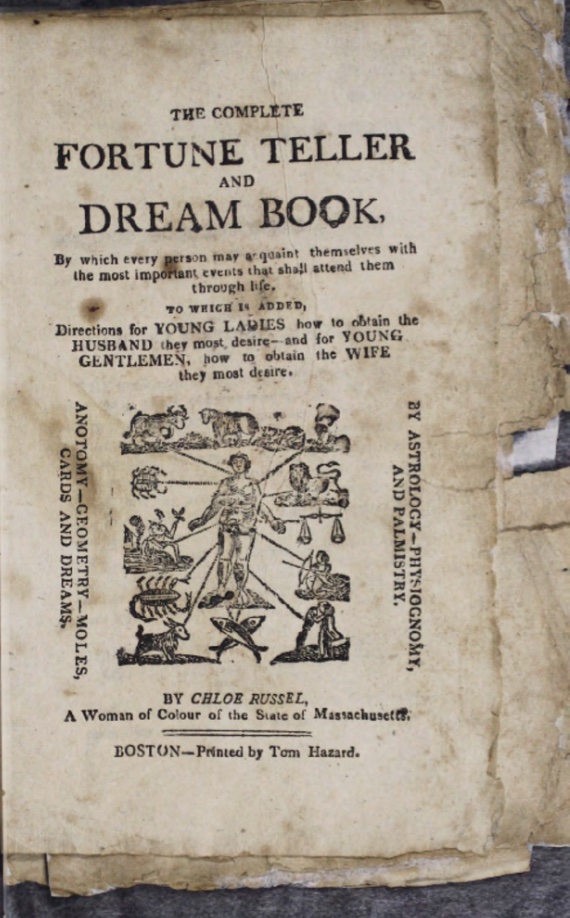

Although much of Chloe Russel’s background is shrouded in mystery, one of the intriguing things about her text is the way it seems to be in conversation with themes of domesticity, matrimony, and femininity, that were circulating at the time, many of which would have appeared in newspapers of the day. In any time period, newspapers and articles serve as a key way to look at the past and see what was relevant to society at a time because what was covered was carefully chosen to fit what society would have appreciated at this time. Additionally, historically Black newspapers or those with a Black publisher would provide even better context to consider Russel’s audience. By examining the parallels between themes of womanhood, domesticity, and matrimony in Russel’s text and expectations of women articulated in these newspaper articles, Rusels’s purpose, and audience might become clearer.

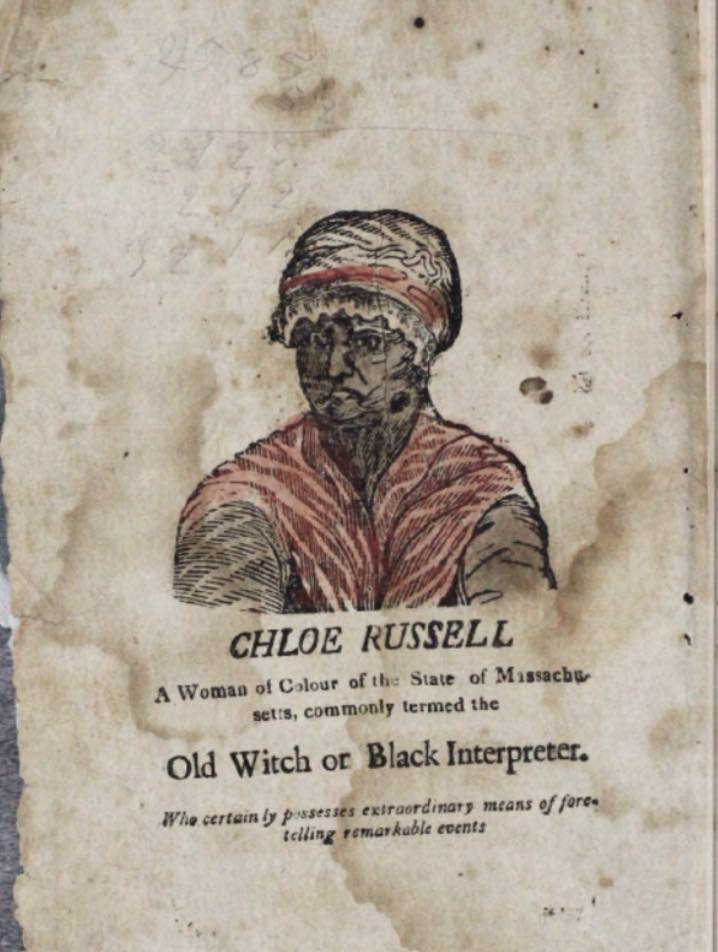

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book.

“... I dreamed that I saw my father, who told me that he had just come from the world of spirits, where there was nothing but joy and happiness-he informed me that he was killed by the fire of the Baccaranas, twenty moons after I was captured by them, in attempting to rescue my mother, whom they had taken––he said that he had been made acquainted with my resolve to destroy myself, and had come to persuade me not to do it, as it would soon be well with me, and I should be free from my master. This singular dream made such a deep impression upon my mind, as to deter me from committing suicide the succeeding day…” –– From The Complete Fortune Teller (Gardner 271).

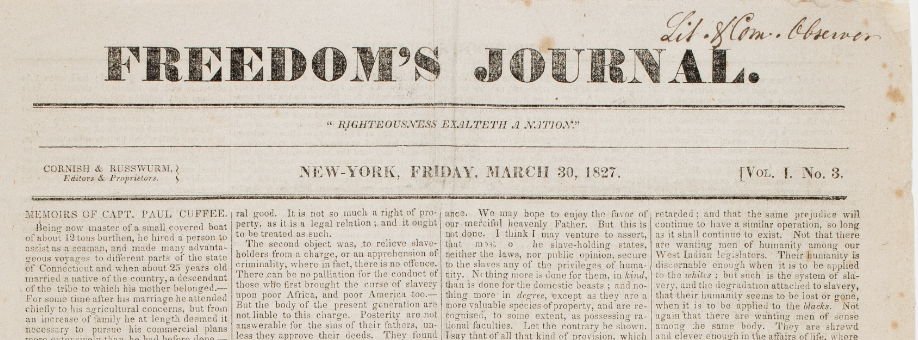

“Freedom’s Journal (v.1: no.1),” Internet Archive, April 16, 1827, Newspaper.

Founded in 1827 and operated for two years, Freedom’s Journal was the first African American newspaper circulated in the U.S. and based out of New York City, eventually reaching 11 states.1 Moreover, as an entirely African American newspaper, news, and content featured within Freedom's Journal were generally suited for African Americans because it was created by African Americans to counter the outward racism in the general press.2 Along with sections featured in the newspaper there was a subsection titled “Varieties” which included information outside of the realm of typical news coverage. Similar to commentary or an opinion section, stories from Varieties instead focused on broad subjects. Several articles focused on issues of domesticity, femininity and the home.

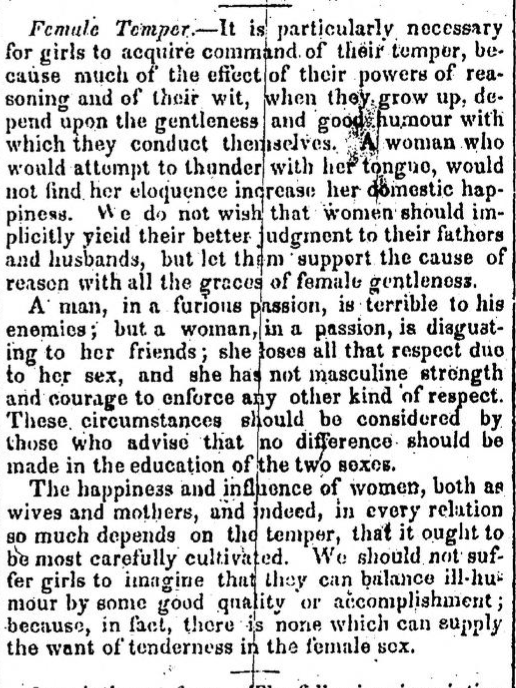

For example, in a piece, titled “Female Temper,” it portrayed the importance of notions of temper for 19th century women. The unknown writer explains it as “particularly necessary for girls to acquire command of their temper,” illustrating what society, more specifically Black society, expects of women. The piece explicitly states how they should react in comparison to men. In the second paragraph, the article says, “A man in a furious passion, is terrible to his enemies; but a woman, in a passion, is disgusting to her friends; she loses all respect due to her sex, and she has not masculine strength and courage to enforce any other kind of respect.”3 Here, the stark difference between expectations and societal views of men and women was at the forefront of the article. The writer removed all validity from the female identity, portraying it instead as a lack of strength, to which the writer gendered” Happiness, instead, was attributed to being a wife and a mother, yet the main issue the article indicates, was the idea of temper, reiterated in the piece through the constant framing of women as difference –– both in their very existence but also in their attitude as well. Ultimately, from the angle of this, the attitude toward women and the female identity was structured upon the idea that women cannot speak up, silencing women of this time.

“Varieties: Female Temper,” Freedom’s Journal, Internet Archive, April 20, 1827, p. 24.

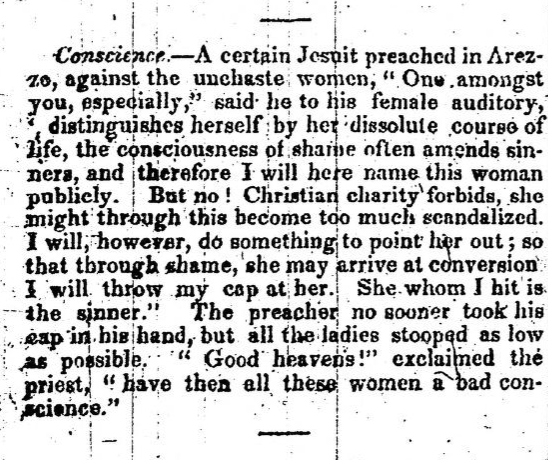

The second piece from“Varieties” deals with a sermon against “unchaste” women.4 This article reiterates the idea that women are supposed to be coy, meek, and not too improper. This type of article seemingly has no relevance to the others, illustrating how certain expectations of women are ingrained within society’s fabric. Its inclusion is misogynistic in a way, as the women, once again, have submitted to society’s expectations. Although a piece from “Varieties” like “Female Temper” was more explicit in its portrayal of women as lesser, this article shows that a coy, nurturing, and gentlewoman was preferred over an unchaste or seemingly improper one.

“Varieties: Conscience,” Freedom’s Journal, Internet Archive, April 27, 1827, p. 28, Newspaper.

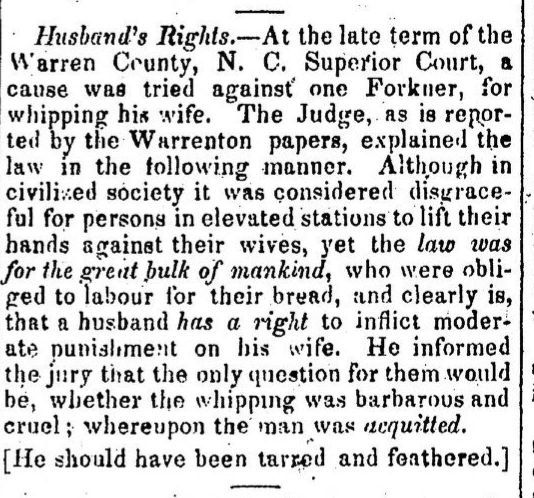

In Freedom’s Journal, the article, “Husband’s Rights,” dealt with themes of domesticity through a trial regarding spousal abuse and subsequent acquittal. It provides an interesting perspective on marriage. Unlike some of the other excerpts from Freedom’s Journal, this article sides with the woman, as the aside says “He [the husband] should have been tarred and feathered.”5 However, the headline was still problematic. “Husband’s Rights” indicated that the case, and the subsequent news coverage and reporters, grappled with whether the husband had the right to abuse his wife, with absolutely no regard for the wife By doing so, it is clear that still, the man took priority in the news coverage, no matter if he was at fault. Ultimately, this inclusion of this news shows what society deems as important.

“Domestic News: Husband’s Rights,” Freedom’s Journal, Internet Archive, May 11, 1827, p. 35. Newspaper.

Each of the articles from Freedom’s Journal was published in 1827 –– the same time Russel published her dream book. Therefore, the audiences would likely be the same, as each article echoes themes found in Russel’s text. In the aforementioned excerpts, she presents marriage as aspirational –– a concept to which all women can aspire to. She writes, “If you dream you are in company with a young man, whose person and conversation is pleasing to you, you may depend that you will one day become the wife of some agreeable companion.”6 Here, the dream functions not only as a recurring symbol but also implies longing and a prolonged need for something out of reach. Marriage is presented as a dream for women to aspire to as if their purpose is to get married, In “Female Temper,” happiness is equated with entrance into the domestic space and is even defined as “domestic happiness.”7 Russel’s text finds solace in similar ideals by presenting marriage as something akin to aspiration and the norm. By actively including and alluding to these societal norms within her text, Russel follows what is expected of women in this time period; however, she seemingly does so fitting the dream-like aspect.

A Method by which a Young Lady May Know Whether She is Ever to Marry:

In the full of the moon, write the name of any man on a piece of clean paper, fold it in the form of a heart, get a gill of red wine and dip it in it, then drink the wine in three draughs just as you are going to bed, put the paper under your pillow and let matrimony be your thoughts until you fall asleep––if you dream you are in company with a young man, whose person and conversation is pleasing to you, you may depend that you will one day become the wife of some agreeable companion––but if you dream that you are disgusted with the appearance and conversation of the young man, you may safely calculate on dying an old maid.(Gardner 273-4)

Satirical Themes in The Women’s Era & Its Relevance with Russel

The Women’s Era, a 19th-century Boston-Based publication that featured satirical articles about domestic spaces and womanhood, published monthly toward the end of the 19th century, was prominent with African American women’s rights leader Josephine Ruffin as its publisher. This publication challenged Russel’s ideas and the larger societal expectations of women in a way.

Ruffin, Josephine St. Pierre, The Woman's Era (v.1: no.1), Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department, March 17, 1829, Newspaper.

Domestic Science looks at domesticity from a satirical standpoint. The unknown writer implies a hierarchy between men and women in the working field, deeming it a “division of labor.”8 Moreover, this division implied that housewives must learn, or else. Because the audience for The Women’s Era was likely women who digested the news within a radical or feminist context, the satire presented here would be clear, indicating that the writer finds it ridiculous that women are subjected to such a division in society. Contrasting a Freedom’s Era, this article was published in 1894, so perhaps society’s view of women and this cult of womanhood, especially within women themselves, shifted and evolved. “Domestic Science” played with society’s rules to show that the domestic space is not a woman’s only space.

Men long ago learned that better work was done by division of labor. This lesson housewives will be forced to learn if they do not want to sink beneath a mountain of toil and trouble and become mere stolid, patient drudges. It is a law of nature that there is a corresponding loss for every gain, and the gain in mental culture to the inhabitants of cities has been attended by a loss in physical strength (“Domestic Science”).

“Women at Home: Beginnings,” broke down societal norms regarding women’s fashion by describing how being well-dressed can sometimes be a “terrible burden” writer and editor Elizabeth Johnson, implied that aesthetic style and attire have ultimately become too complicated, instructing readers to wear what they want. Fashion was based on what is popular or trending, and Johnson seemed to oppose that notion, arguing that women were bound by the changes in fashion.9 Johnson struck down the idea of a cult of true womanhood by providing a new definition for style –– fashion was a choice and not necessarily a restriction Ultimately, this article served as a glimpse into a society that is defined by the expectations of women, seen through this requirement to fit into a trend, style, or fashion.

Women live too largely and broadly in this time, to be bound down to every change of sleeve or skirt, besides this, sensible women will not long consent to give up at the command of unknown rulers, fashions which are sensible and comfortable ... It is to be hoped however, that whatever the future brings us, it will let us keep blouse waists, loose outside garments and short skirts. These all have the true beauty, the beauty of appropriateness (“Women at Home: Beginnings”).

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book.

Russel’s text is a clear indicator that domesticity and matrimony were a norm in early 19th century, Black society. Through a closer look at publications, it was even more evident that Russel fit this mold, as newspapers often depict what a society is like and what it appreciates. Because these publications and Russel’s text echo off of one another in terms of the topics/themes they covered, it’s even more evident how newspapers serve as both primary source and contextual element, allowing Russel’s text to be understood as fit for a society that really needed it.

Endnotes

1. “Freedom’s Journal.” Encyclopedia Britannica. November 10, 2020, britannica.com/topic/Freedoms-Journal

2. “Freedom’s Journal.” Encyclopedia Britannica. November 10, 2020, britannica.com/topic/Freedoms-Journal

3. “Varieties: Female Temper.” Freedom’s Journal. April 20, 1827, p. 24. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n23/

mode/2up

4. “Varieties: Conscience.” Freedom’s Journal. April 27, 1827, p. 28. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n27/mode/2up.

5. “Domestic News: Husband’s Rights.” Freedom’s Journal. May 11, 1827, p. 35. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n33/mode/2up

6. Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005, pp. 259–288. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30045526.

7. “Varieties: Female Temper.” Freedom’s Journal. April 20, 1827, p. 24. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/

n23/mode/2up

8. “Domestic Science.” The Women’s Era. March 24, 1894. Emory Women Writers Resource Project, womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/content.php?level=div&id=era1_01.04&document=era1.

9. Johnson, Elizabeth. “Women at Home: Beginnings.” The Women’s Era. March 24, 1894. Emory Women Writers Resource Project womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/content.php?level=div&id=era1_01.10&document=era1.

Bibliography

“Domestic News: Husband’s Rights.” Freedom’s Journal. May 11, 1827, p. 35. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n33/mode/2up

“Domestic Science.” The Women’s Era. March 24, 1894. Emory Women Writers Resource Project, womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/content.php?level=div&id=era1_01.04&document=era1.

“Freedom’s Journal.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 10 November 2020, britannica.com/topic/Freedoms-Journal

“Freedom’s Journal (v.1: no.1),” April 16, 1827. Internet Archive. Newspaper archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n27/mode/2up.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005, pp. 259–288. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30045526.

Johnson, Elizabeth. “Women at Home: Beginnings.” The Women’s Era. March 24, 1894. Emory Women Writers Resource Project, womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/content.php?level=div&id=era1_01.10&document=era1.

Russell, Chloe. The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824. Boston Athenaeum. Book

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Freedom’s Journal.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 10 November 2020, britannica.com/topic/Freedoms-Journal

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 27 August 2020, britannica.com/topic/Freedoms-Journal

“Varieties: Conscience.” Freedom’s Journal. April 27, 1827, p. 28. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n27/mode/2up.

“Varieties: Female Temper.” Freedom’s Journal. April 20, 1827, p. 24. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/FreedomsJournalVol.1/page/n23/mode/2up