Written and compiled by Anna Tobin and Savita Maharaj

Introduction

Living in Boston’s West End, Chloe Russel was part of a thriving Black community, where her text was widely circulated and read, particularly because of the affordable nature of the published chapbook.1 This exhibit aims to provide further historical context to the nature and stakes of Black marriage in 19th century Boston. And, from this information, it can be further analyzed how Chloe Russel and her text fit into — or perhaps go against — the dominant ideals circulating around love and marriage at that time.

Black Marriage in Antebellum New England

Leading up to the Civil War, the legal right for African Americans to marry varied widely and was dependent on the laws and practices of each colony or state. In the South, Black marriages were not legitimized under the law since slave codes prohibited bondmen and bondwomen from entering into marriage contracts. However, the colonies in New England, allowed Black enslaved people to legally wed, “[defining] them as both persons and property before the law.”2

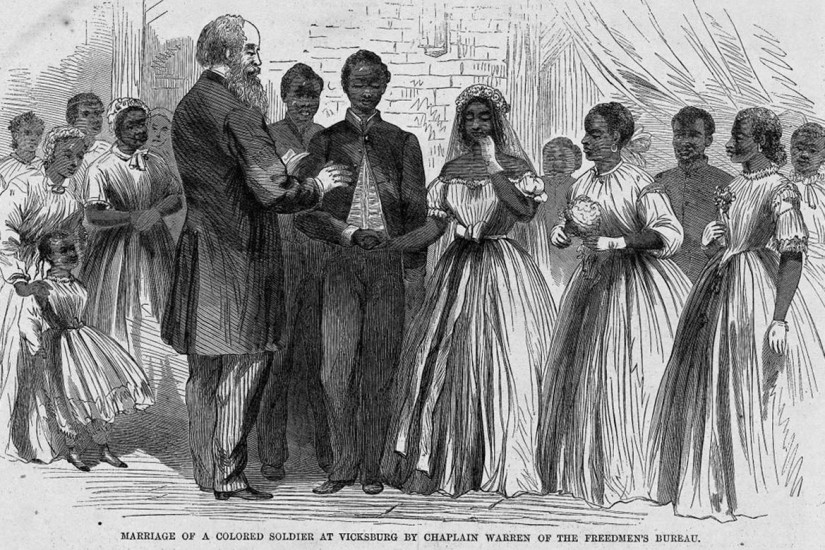

Waud, Alfred R, “Marriage of a colored soldier at Vicksburg,” 1866, Mississippi Vicksburg, 1866, Photograph.

Despite the differences in legality, familial bonds and marriage were important parts in Black lives in both the North and South. In her article expanding on Tera Hunter’s expansive study on Black love in pre-Civil War America, Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century, Vanessa M. Holden summarizes eloquently the complex cultural role that marriage played for both free and enslaved African Americans during this period:

Kinship was essential to Black people and many free and enslaved people valued marriage as a way to signify commitment and love. Marriage was a way to codify intimate relationships. However, it was also an expression of humanity. It was a right that could grant other rights, optimizing its use as an instrument of social control. Marriage was not a failsafe institution with the ability to right racism’s wrongs… Marriage was important, not perfect.3

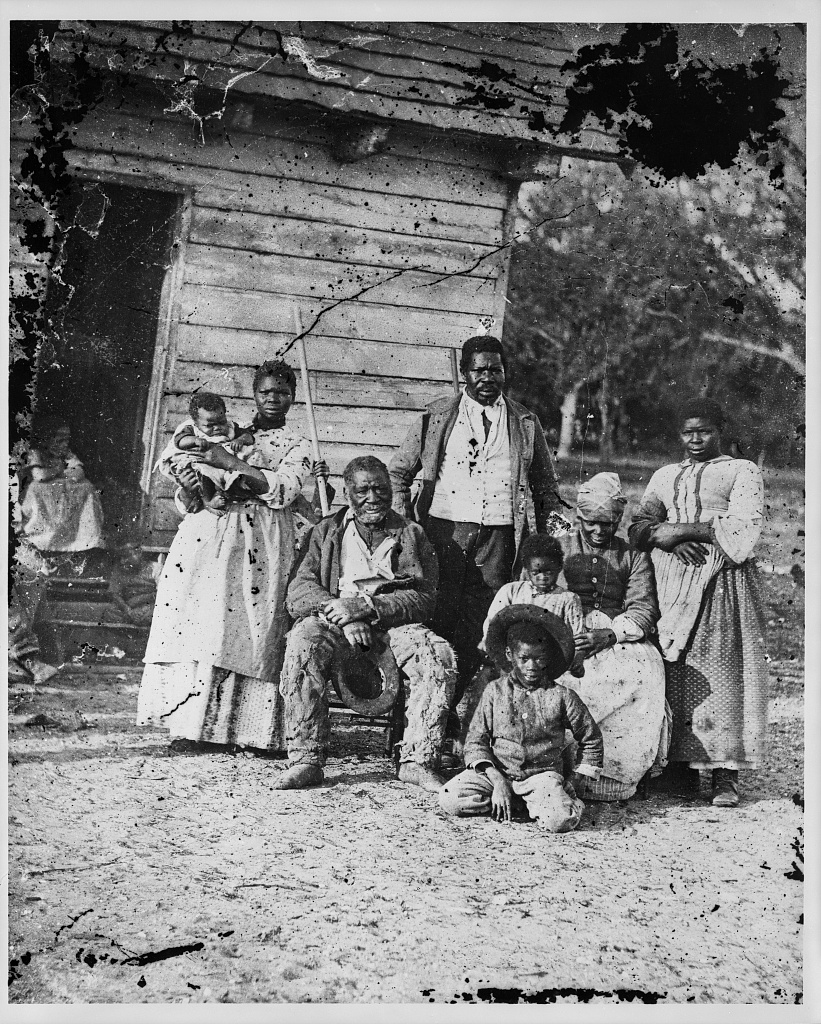

O'Sullivan, Timothy H, “Five generations on Smith's Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina,” 1862, South Carolina Beaufort, [Printed Later] Photograph.

In the North, the effort to legally recognize marriage, even for enslaved peoples, comes from the Puritan moral strictures that heavily influenced colonial New England. Overall, “family was the fundamental unit of Puritan society and the primary vehicle for preserving and perpetuating Puritan ideals.”4 So, to that effect, legally binding unions which discouraged extramarital relations and encouraged the family units inevitably sought to maintain Puritan morality (which applied to both white and Black residents, enslaved or otherwise). Within this system, although still enslaved, bondmen and bondwomen were able to experience glimpses of personhood and equality to whites through the institution of marriage.

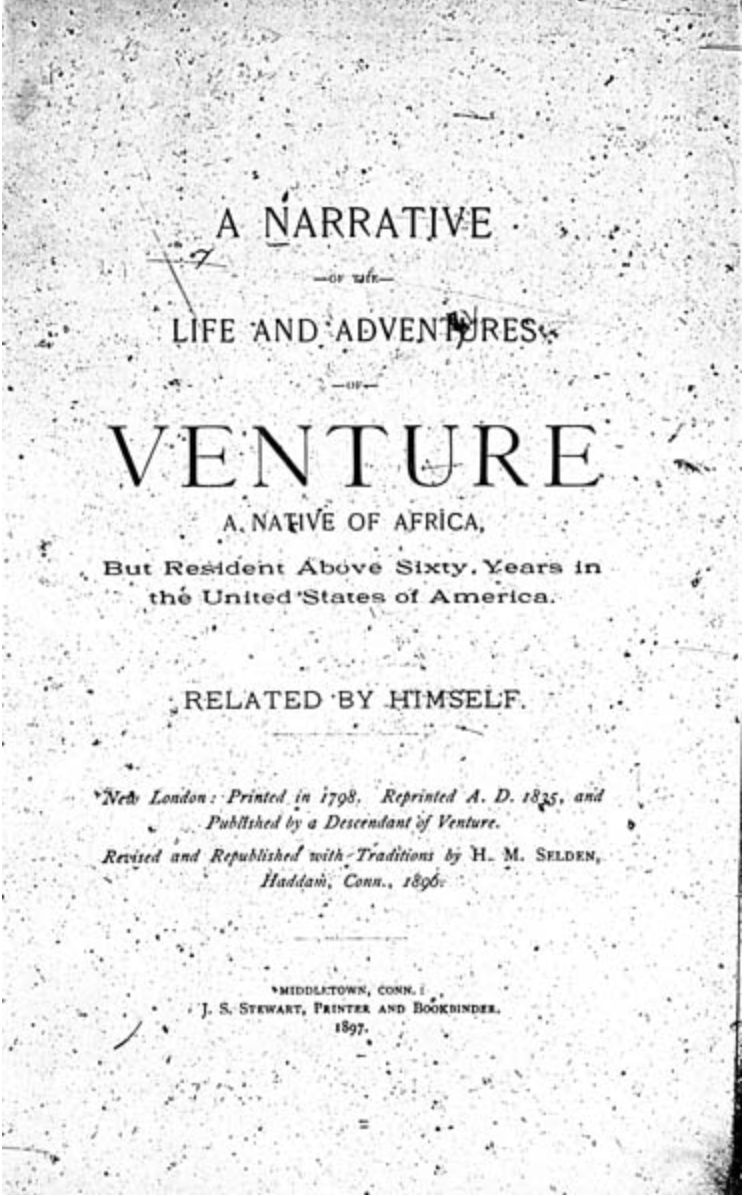

Smith, Venture, A Narrative of The Life and Adventures of Venture Smith, a Native of Africa, but Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself. New London: Printed in 1798, 1798, New London, Book.

And, in cases where one partner was free and their spouse was still enslaved, marriage became a tool through which freedom could be achieved for both parties. One historical example of this situation is the story of Venture Smith and his wife. Taken from West Africa and enslaved in Rhode Island at age eight, Venture met and married Marget (Meg), another of his master’s slaves, by age 22. The two had children together, but Venture was sold to another master and the two were separated. Venture, however, was incredibly opportunistic and was able to negotiate with his master to keep a portion of his wages. Then, “through his industry and entrepreneurship, he was able to purchase first his freedom, then that of his two oldest sons, Solomon and Cuff, and eventually—through their labor as well as his—his then pregnant wife Meg and their daughter Hannah.”5 This extremely impressive dedication to preserving his family unit, in his own words, was what he considered his greatest achievement.6

“Venture Smith Gravestone Gathering,” 2019, East Haddam Connecticut, Photograph.

After Massachusetts abolished slavery in 1783, marriage still existed as an institution that humanized and legitimized African American citizens under the law. African Americans living in New England sought out Boston as a center of commerce where they could establish themselves and their families. As early as the 1830s laws began to grant property rights to married women, and the economic benefit of marriage started to seem more balanced than the traditional patriarchal model.7

Drawing Conclusions About Chloe Russel

Overall, The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book definitely reinforces how important and culturally valuable marriage and finding a spouse was to people of that time. Yet, the depiction of Chloe Russel is antithesis to the benefits of marriage; the opening autobiography of the text paints her as a single woman who was able to earn her own freedom and gain property despite not taking part within the institution of marriage.

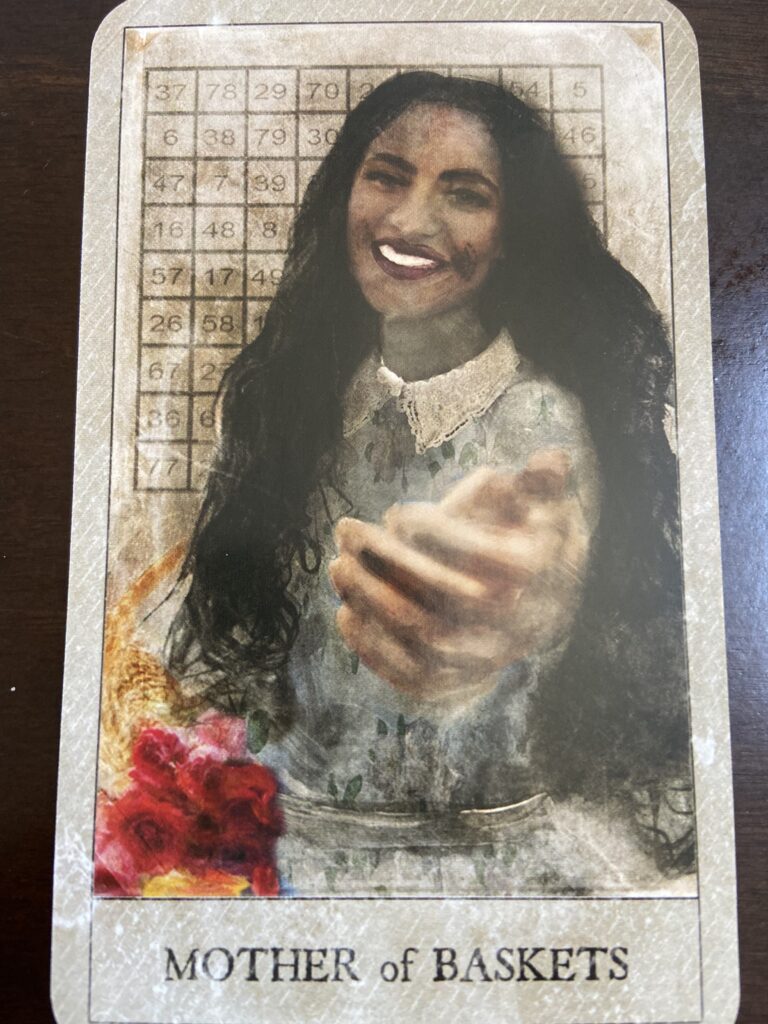

McQuillar, Tayannah Lee, and Katelan V. Foisy, The Hoodoo Tarot: 78-Card Deck and Book for Rootworkers. Rochester, 2020.Vermont: Destiny Books. Image

Russell’s text seems to separate any notion of the Church or Christianity from matrimony, framing it as a “fated” event of life based within fortune and a less rigid understanding of spirituality. This is particularly surprising, considering how Puritan ideals were ingrained within Boston’s founding and New England sentimentalities as a whole. Going against this religious norm could have added a sensational aspect to the text, aiding in its readership and circulation. Equating love to elements of divination — as opposed to God or Christianity — works to remove the concept of marriage from the often oppressive and exclusionary nature of the Church, and instead lets it exist as a connection to spirituality, the body, and African practices of witchcraft. In this way, Russel’s text can work as a way through which Black authorship and readership sought to reclaim a practice that had been heavily entrenched in Western, white oppression.

Endnotes

1. Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (JSTOR, 2005) 259

2. Catherine Adams and Elizabeth H. Pleck, “Marriage and the Family,” in Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010) 104.

3. Holden, Vanessa M.“Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century,” (AAIHS, 2018) https://www.aaihs.org/slave-and-free-black-marriage-in-the-nineteenth-century/.

4. duCille, Ann. “Blacks of the Marrying Kind: Marriage Rites and the Right to Marry in the Time of Slavery,” (Differences 29, no. 2 September 1, 2018): 24, https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-6999760.

5. duCille, Ann. “Blacks of the Marrying Kind: Marriage Rites and the Right to Marry in the Time of Slavery,” (Differences 29, no. 2 September 1, 2018): 24, https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-6999760. 23

6. Ibid 24

7. Megan Way McDonald, Family Economics and Public Policy, 1800s-Present (New York, NY: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2018). 14

Works Cited

Adams, Catherine, and Elizabeth H. Pleck. “Marriage and the Family.” Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England. Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2010.

duCille, Ann. “Blacks of the Marrying Kind: Marriage Rites and the Right to Marry in the Time of Slavery.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2. Brown University, 2018.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2. The New England Quarterly, 2005.

Holden, Vanessa M. “Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century.” Black Perspectives, aaihs.org. 2018.

McQuillar, Tayannah Lee, and Katelan V. Foisy. The Hoodoo Tarot: 78-Card Deck and Book for Rootworkers. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books. 2020. Image

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book

Smith, Venture. A Narrative of The Life and Adventures of Venture Smith, a Native of Africa, but Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself. New London: Printed in 1798. New London, 1798. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/venture2/venture2.html.

“Venture Smith Gravestone Gathering.” East Haddam Connecticut, 2019. Photograph. https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2021/09/venture-smith-the-first-slave-narrative/

Waud, Alfred R. “Marriage of a colored soldier at Vicksburg.” Mississippi Vicksburg, 1866. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009630217/.

Way, Megan McDonald. Family Economics and Public Policy, 1800s–Present: How Laws, Incentives, and Social Programs Drive Family Decision-Making and the US Economy. Babson College, 2018.