Created by Mary Bancroft & Savita Maharaj

Introduction

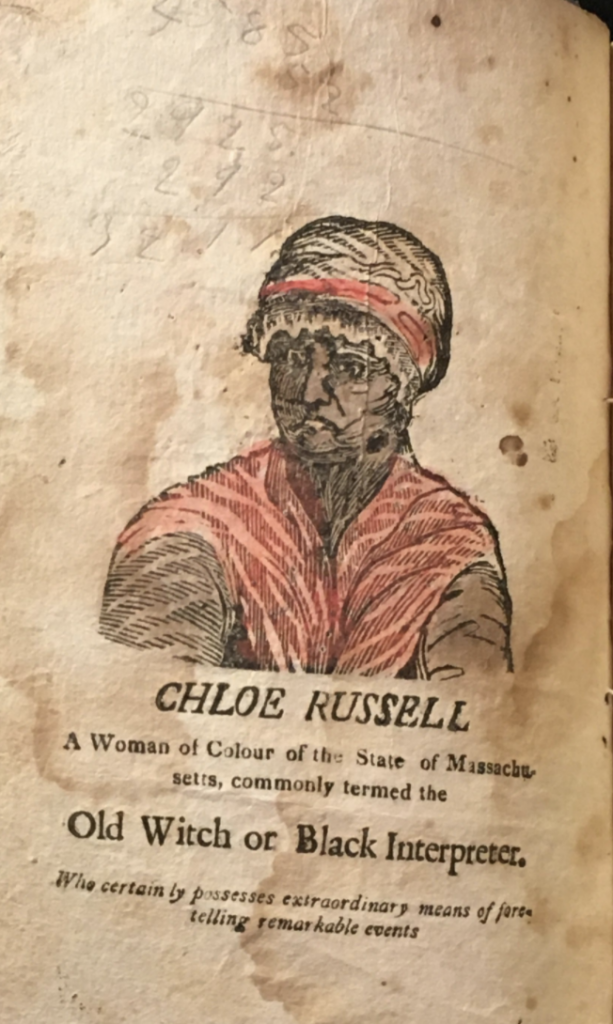

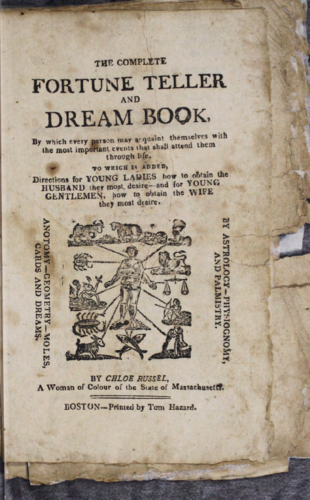

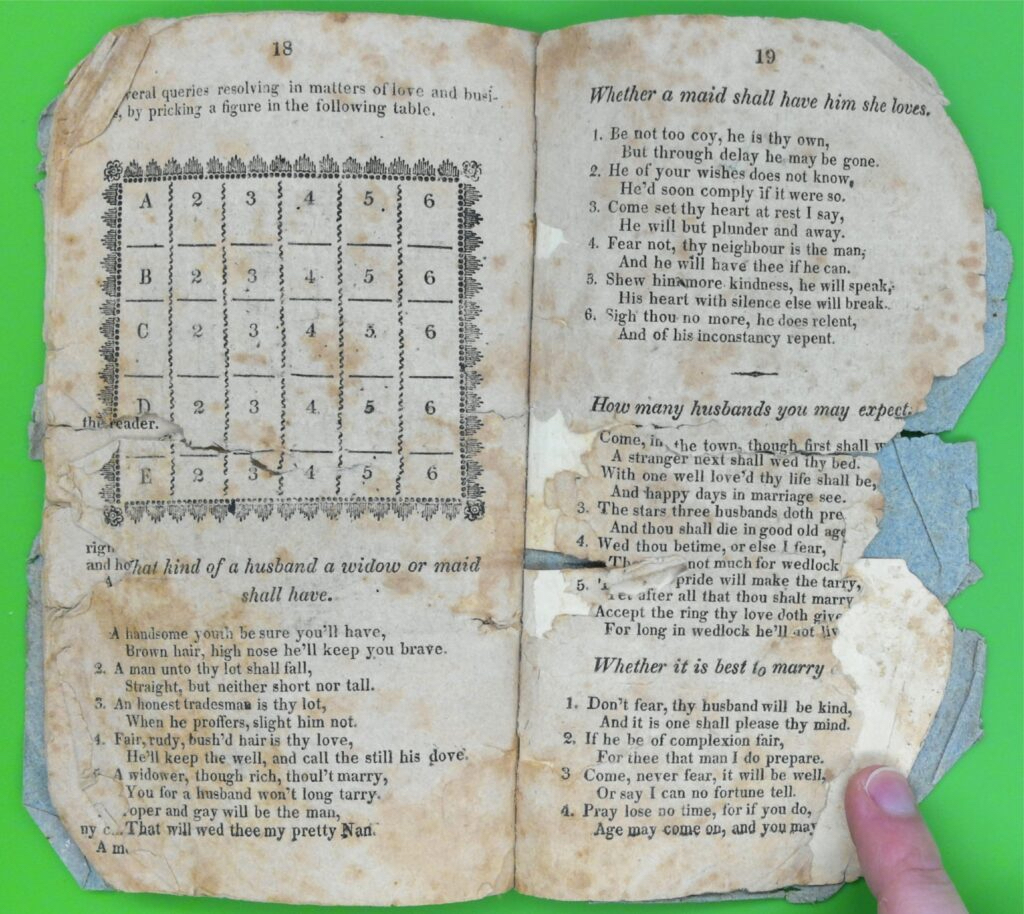

The byline of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book reads “by Chloe Russel, A Women of Colour, in the State of Massachusetts.” Yet, questions around the identity of the author remain. Eric Gardner found that a Black woman named Chloe Russel did indeed live in Boston during the 1820s, so there is a very likely possibility that she wrote the text. However, the text also has inconsistencies that call this option into question – such as the the presence of “Tygers” in Africa, George Russel (who the narrator claims to have been her master) does not exist.1

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

If the author of the text is not Chloe Russel of Boston, then who is it?

Gardner raises the possibility that it was an invention of a white publisher who highlighted the Non white origins of the text to promote sales. The stereotype of the African American fortune teller had been popularized in other works of the time and many fortune tellers and healers in New England were of African descent during the nineteenth century. Perhaps a white publisher invented Russel in the hopes that the stereotype of Black people being linked to the occult would lend credibility to the dream book. Garder also mentions the possibility that Boston’s real Chloe Russel was a fortune teller and the publisher was hoping to use her reputation to sell copies.2

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

While it is probable that The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book was authored by a Black woman named Chloe Russel, this site will examine the possibility that it was not. Was it common for White authors to appropriate Black identities in the nineteenth century? What other similar instances occurred?

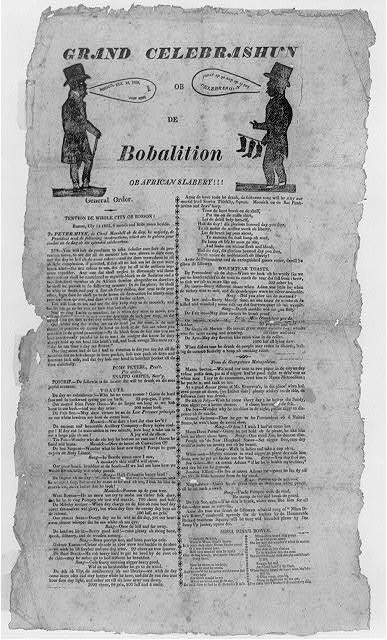

Bobalition

In Northern nineteenth century broadsides and newspapers, white authors satirized African American celebrations of the anniversary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, termed “Bobalition”, in a way that reinforced ideas of racial difference. In this satire, white authors would pretend to be Black in their writing. While it was understood that they were really white and performing parody, their practices still contributed to conceptions of the character and behavior of African Americans. 3

“Bobalition of Slavery,” 1832, Boston Massachusetts, Photograph.

“Bobalition'' writings included “jokes”, cartoons, political commentary, and fiction that depicted African Americans as deviant and developmentally challenged, using stereotypical dialect. For example, in “Grand Bobalition of Slavery”, which appeared in Boston in 1820, the speaker, named Cato Cudjoe, conveys a message that makes little sense. In a stereotypical dialect, he threatens his audience with violence, claiming that if they do not adhere to his wishes he will “get a broke head, and dareby hab de nose- bleed on de shin”. He also flouts conventions of etiquette. Although he begins his message with a polite “Dear Sir”, it is followed by “You Great Rascal!”, an improper form of address. He claims he is the president and then misuses that supposed authority by bragging about his power to “knock you down if I like.”4 This caricature conveys Cudjoe as violent, less intelligent, and deviant, conforming to harmful stereotypes about Black men and associating these traits with Blackness.

“Bobalition of Slavery,” 1832, Boston Massachusetts, Photograph.

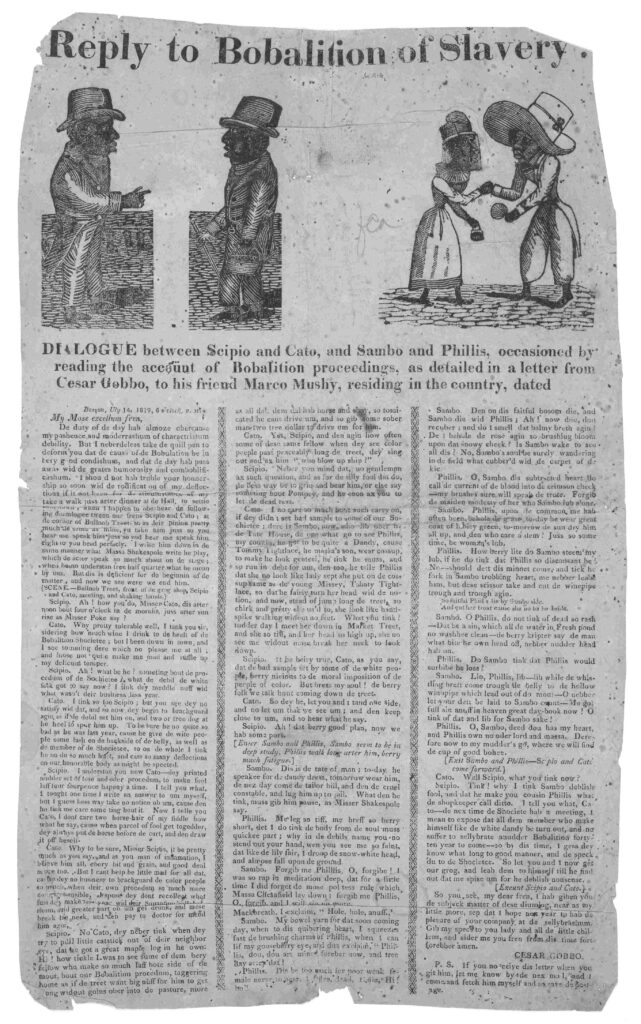

In “Reply to Bobalition of Slavery” which appeared in Boston in 1819, the cartoon attributes lack of discipline to Blackness and orderly behavior to whiteness. It contains conversations between four Black speakers, Scipio, Cato, Sambo and Phillis. Again, the exchanges take place in a stereotypical dialect. Sambo and Phillis waste the little money they have on stylish clothes. Because he was unable to pay the debt he incurred when purchasing a suit, Sambo spent time in jail. Scipio and Cato speak as if two white celebrants who behaved rowdily at a party were acting outside the social norm.5 Thus, the white author entrenches ideas of racial difference. It is the norm for white people to behave in a more restrained manner. On the other hand, the representation of the Black individuals perpetuates racist stereotypes about Black irresponsibility with money and criminality.

“Dreadful Riot on Negro Hill!,” 1827, Boston Massachusetts, Photograph.

In an increasingly anti-slavery North, Bobalition write ups helped reinforce racist notions of differences between Black and white people, attributing negative qualities to Black individuals. Furthermore, they replaced reports of what was actually happening at Abolition Day celebrations, allowing white writers to erase real and diverse African American cultural practices with their harmful, racist parody.6

White People Writing Black Memorial Texts

Some of the earliest narratives of Early African American life are texts written in memoriam, such as obituaries and memoirs. These were often written by White authors. Although they were not claiming to be Black in their texts, they exert great power over the representation and legacy of the Black individuals whom they are writing about.7 Their subject is dead, unable to contest the contents of their story. Thus, the White author can retell the story of their life in a way that they prefer.

Lucy Terry Prince

This is evident in the obituary of Lucy Terry Prince, an activist and the first African American poet. Although Terry Prince was a slave for twenty-four years, her obituary glosses over that aspect of her life. It calls her a “woman of color” but never uses the words “slavery” or “enslaved”. Instead, it focuses on her spirituality, highlighting the year of her baptism. While it praises her gift for speech and intellect, it ignores many of her most significant achievements, such as her poetry, her being the first woman to argue before the Vermont Supreme Court, and her passionate advocacy for her childrens’ right to education and against discrimination. Instead, her speech and intellect are confined to the context of her religion and community ties; her “knowledge of the holy scriptures” is praised as “uncommonly great”, and she was “respected among her acquaintance” but only because “her memory was precious.”8 By ignoring Terry Prince’s enslavement and accomplishments in favor of her commitment to faith and favor with the community, the obituary retells the life of a Black pioneer in a way more palatable to White Protestants.

Minks, Louisa. “Lucy Terry Prince.” Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield MA. Painting

Phillis Wheatley Peters

A similar example is the memoir of Phillis Wheatley Peters, the first African American author of a published book of poetry. She has been a controversial figure due to her supposed lack of distaste for slavery. Yet, much information known about Wheatley’s life is from the questionable Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave, a biography written by Margaretta Matilda Odell, who claims to be a relative of Wheatley Peters’. Her familial ties cannot be proven and whether Odell or another Boston author, B.B. Thatcher wrote the text is questionable. The biography may have contributed to Wheatley Peters’ controversial status. It skims over the horrors of her capture and journey on the Middle Passage and paints her masters, the Wheatleys, in a sympathetic light. In particular, Susannah Wheatley is praised as a “kind mistress” who was only seeking a “faithful domestic” and graciously taught her to read and write. While the Wheatleys may have had some redeemable qualities, their support of slavery should not be disregarded just because they may have been relatively kind to one of their slaves. Additionally, the biography contains inaccuracies about Wheatley Peters’ husband that perpetuate stereotypes about Black men being unfit fathers and husbands. Odell describes him as “too proud and too indolent”, “negligent” of his wife, and unable to provide for his family. She even speculates that he may have sexually abused his wife. This portrait aligns with stereotypes of Black men as being lazy, predatory, and unreliable fathers and there is little information to corroborate it beyond Odell’s testimony. Her credibility is questionable, as her account of Wheatley Peters’ marriage also includes falsehoods: census records indicate that Peters remained in Boston at least six years after his wife’s deaths, while Odell claimed he moved South, and Odell’s claims that Wheatley Peters did not use her married name have been disproven by her uncovered letters.9 The legacy of such a remarkable Black woman was heavily impacted by a White woman who conveyed her White slave masters as better for her than the Black man she chose for a husband.

Wheatley, Phillis, The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley, 1988, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, Image.

Chloe Spear

This White washing of Black stories is also evident in the memoir of Chloe Spear, a Black property owner in Boston. Her biography was published over seventeen years after her death, written by the anonymous “Lady of Boston '' thought to be one of two White women. Like with Terry’s obituary, a significant focus of the biography is Spear’s religious conversion. While it does detail her capture from Africa and painful forced separation from her family, the rest of the text follows Spear’s efforts to become a Christian.10 Like with Wheatley Peters’ memoir, her relationship with her White masters is portrayed as superior to that of hers with her husband. The author writes that Spear shared a “family-like attachment” to her masters who provided her kindness and comfort, while she was “not very ardently attached” to her husband, who is represented as idle and irresponsible with money.11 As with Wheatley Peters, the White masters’ complicity with slavery is overlooked while racist stereotypes damage the portrayal of Spear’s husband.

Spear, Chloe, 1832, Memoir of Mrs. Chloe Spear, a Native of Africa, Who Was Enslaved in Childhood, and Died in Boston, January 3, 1815 ... Aged 65 Years. Boston, Book.

The purpose of the text seems to be political in nature, using Spear’s life to promote missionary intervention in Africa. Spear is said to have spoken of her capture and enslavement with “devout gratitude” as it gave her the chance to “be made acquainted with the gospel”, the introduction proclaims that a portion of the text’s proceeds will be given to “Schools in Africa”, and the author concludes with the hope that the “unenlightened” in Africa will be taught to read scripture. Spear’s life, which scarcely exists in the narrative outside of her spirituality, seems to be merely a vessel for the author to push her agenda. The contents may not even all be true; the text provides specific thoughts from Spear despite being written around seventeen years after her death, and the author makes no effort to explain how she knew Spear or establish credibility beyond stating “It is true” in the preface.12 If there are indeed falsehoods or exaggerations, the author demonstrates a lack of respect for Spear’s life and story.

All three of these instances of White people authorizing Black stories showcases how White authors can both whitewash Black lives and reinforce racist tropes. By diminishing Spear’s and Wheatley Peter’s husbands, the authors support negative views of Black men. By focusing on Spear and Terry Prince’s spirituality over their achievements, the authors downplay their excellence. And by disassociating Wheatley Peters and Terry Prince from their African childhoods and characterizing all three women’s slave masters as kind, the authors evade the evils of slavery and craft a narrative more comfortable for White people.

Slave Narratives

A common tool to advocate for the abolition of slavery during the nineteenth century was the slave narrative, true stories about the experiences of fugitive slaves that demonstrated the horrors of the system. They became wildly popular, especially in the North. Although most slave narratives were written by Black authors, some White authors created pseudo-slave narratives. This was done out of the support for the cause of abolition, but also for profit13

Hildreth, Richard, The Slave: Or Memoirs of Archy Moore, 1836, Boston, Book.

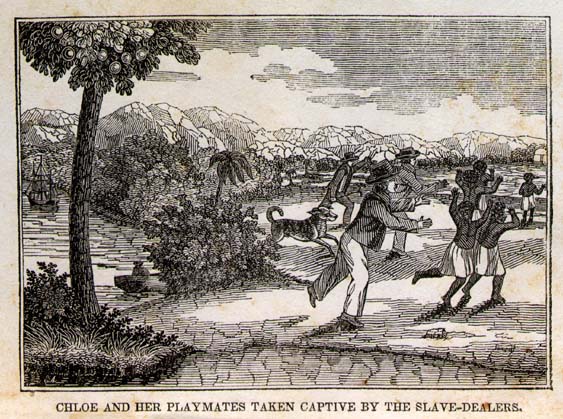

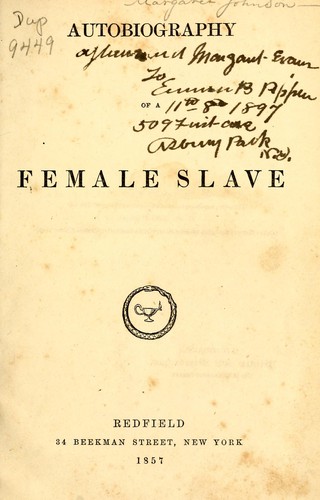

Two of the most well-known pseudo-slave narratives by White authors are Richard Hildreth’s The Slave: or Memoirs of Archy Moore and Mattie Griffith’s Autobiography of a Female Slave. Both authors falsely assured their readers in the beginning of their works that the contents of their stories were true events that happened to them. Yet, despite the fact that they were appropriating Black identities, both authors incorporated anti-Black elements into their texts. Hildreth’s protagonist is described as only having “some imperceptible portion of African blood” while Griffith’s narrator’s skin “was no perceptible shade darker than that of my young mistress”. Additionally, Griffith’s narrator is complimented by another slave for talking like “dem ar’ great white scholards” who expressed surprise that “a poor darkie could larn so much”. These comments are rife with colorism or conform to the racist stereotype at the time that Black people were not as intelligent. Although both authors sought to profit from telling Black stories, they wanted to situate their Black characters close to Whiteness, claiming they were superior to other Black people in doing so.14

Browne, Martha Griffith, Autobiography of a Female Slave, 1998, Jackson: Banner Books/University Press of Mississippi, Book.

The two narratives were quickly exposed as fictitious. Still, they were accepted and reprinted, Hildreth’s text being reprinted in seven more editions. A review for his work in The New York Plaindealer said, “Fiction never performs a nobler office than when she acts as the handmaid of truth.” Reviews for Griffiths’ narrative emphasized the authenticity of its emotion, despite the falsity of its facts. The Liberator assumed it was false but commended it as “the production of an elevated and a philanthropic heart."15

Garrison, William Lloyd, and James Brown Yerrinton. "The Liberator." January 7, 1832, Boston, Mass: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp, Newspaper.

This contrasts with the treatment of Black authored slave narratives. Northern newspapers engaged in fear mongering about Black people pretending to be ex-slaves, labeling them as “scoundrel”, “swindler”, and “imposters” and claiming that such instances were frequent. Narratives based in reality by Black writers fought off accusations of lying with corroborating documents and testimony from White abolitionists. This system assumed the Black authors were untrustworthy and placed the responsibility on the White gatekeepers to verify their stories. James Williams’ Narrative of James Williams, a text by a Black man that was exposed as false, was received quite differently than Hildreth’s and Griffith’s. The New York Commercial condemned the group who sponsored the narrative, the American Anti-Slavery Society’s, “jesuitism by which the public were gulled”, blaming the White abolitionists for the deceit, not the author, as if he were expected to be untruthful. Unlike Griffith and Hildreth’s situations, the sale of the narrative was discontinued after about one month of publication.16

White writers posing as Black people to write slave narratives faced privileges that Black authors did not. If found to be fraudulent, their texts were still typically accepted and at least moderately successful, unlike with Black authors. Even worse, they used their appropriate identities to publish and strengthen anti-Black sentiments and stereotypes. Another privilege included more flexibility in style. Hildreth and Griffith’s works deviated from typical slave narratives, containing dramatic romance plots, suicide or pirates, and florid language.17 On the other hand, Black authors were often told to stick to writing the facts and maintain a focus on the violence and cruelty of slavery. Slave narratives with Black authors were frequently edited or censored by White abolitionists, who sponsored the narratives to advance their own political beliefs. The importance of the slave narrative as a tool of agency and power for ex-slaves should not be understated, but White abolitionists did limit what and how former slaves could write. They did not want their narrative to lose credibility by advancing beyond what Black people were thought to be capable of, such as complex storytelling and philosophy.18

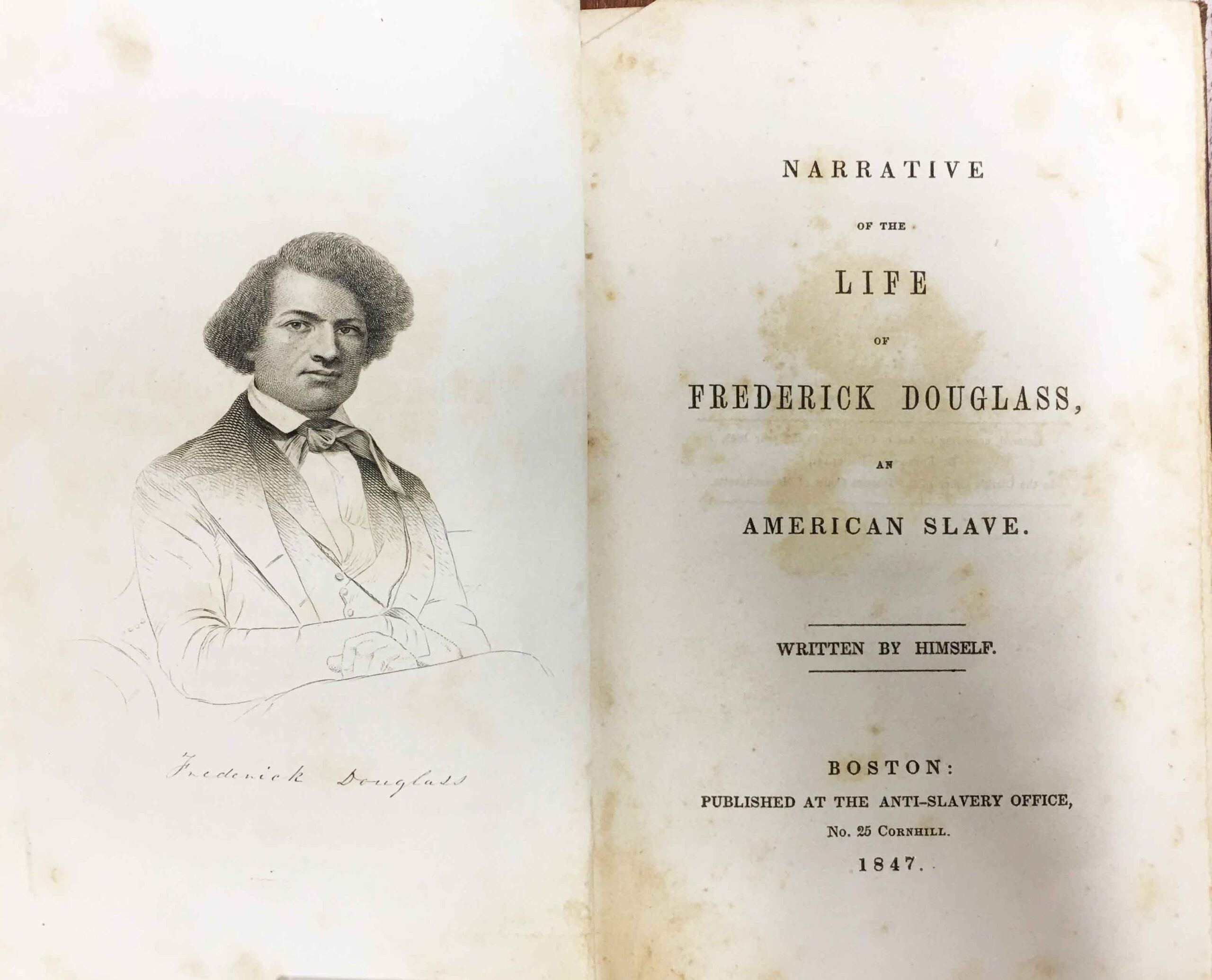

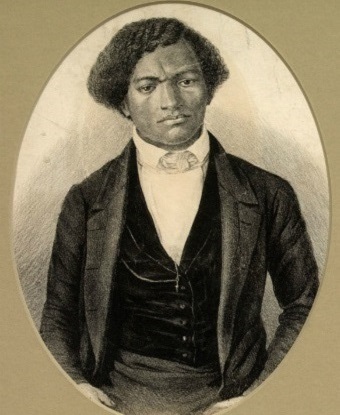

Douglass, Frederick, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself,” 1845, Boston, MA.

Frederick Douglass’s two slave narratives show this phenomena. His Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass was promoted by White abolitionists, whom he eventually distanced himself from, as he was not satisfied with their restrictions. He then wrote his second narrative, My Bondage and My Freedom, with less censorship. A comparison of the two shows that his earlier work focuses more on specific injustices Douglass experienced as a slave, such as beatings and the denial of an education, while the second more thoroughly connects those instances to a systematic critique of the institution of slavery. For example, in his first narrative, he discusses how it harms him when his master forbids his mistress from educating him. In the second, he describes how this not only disadvantages him but corrupts her, making them both “victims to the same overshadowing evil.”19 Furthermore, in his first narrative, he details how his White shipyard co-workers found it “degrading” to work with him out of fear that Black workers would cause poor Whites to be “thrown out of employment.”20 In My Bondage and My Freedom, he goes further and connects this fear to the lack of class consciousness between poor Whites and Black Americans and predicts the “over throw” of slavery were that to be reversed.21

“Frederick Douglass,” National Park Service.

While White abolitionists that edited slave narratives were not pretending to be Black, their positions as editors and sponsors allowed them to censor Black stories and limit the ability of Black writers to speak outside their personal experience about broad, societal issues. Instead of leaving the philosophy of slavery to those who lived it, they assumed they were the only effective mouthpieces and used their power to silence those with more authentic voices.

How does Russel fit in?

Throughout history, White authors writing Black stories have used and distorted them to advance their own agendas, perpetuated anti-Black stereotypes, and modified Black stories to be more palatable to White people. These actions are more hurtful in context. Because of the disadvantages Black Americans faced in Early American publishing, they were underrepresented in books and other written works. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, fewer than thirty books by Black authors were published in Great Britain and the United States, excluding the abolitionist movement slave narratives. This scarcity made it more difficult to offer authentic Black stories and dispute negative accounts and appropriations of African Americans. Thus, when White authors wrote Black stories in harmful ways, they had significant power in shaping conceptions of Black people.22

Early African American literature contributed significantly to forming White ideas of the meaning of Blackness, as early Black authors used writing to assert their humanity. During the Enlightenment era, a popular argument was that because Africans had supposedly not mastered the arts and sciences like the Europeans, they were of a different, less intelligent species. The literature of Early Black writers helped prove that African Americans were equally as human. Yet, this could also make a White appropriation of Black authorship more damaging, as if it was racist or poorly done, it could support the argument that African Americans were less human.23

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

In appropriating Black identities, White people are able to use the identity for their own end while retaining the social benefits of Whiteness. The authors of the Bobalition broadsides were able to profit from and disseminate negative portrayals of Black Americans, the author of the Chloe Spear memoir was able to advocate for missionary intervention in Africa, and White abolitionists were able to convert other White people to their cause. Yet, once their purpose was achieved, they could return to their life without slavery or segregation or discrimination in housing, education, criminal justice, and beyond.24

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

If the Russel text was written by a White person that tried to use the stereotype of Black women as more linked to witchcraft in order to profit, it may be another instance in this pattern of Whites writing Black stories to benefit themselves and their goals. Whether or not that author’s action would have been harmful is not determined on this site, but regardless, it would fit into the history of often damaging White appropriation of Black authorship and identity in 19th century writing.

Endnotes

1 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 259 - 268

2 Ibid

3 Cohen, Lara Langer, and Stein, Jordan Alexander. The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture. (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) 107-126

4 Ibid

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

7 Brown, Lois. “Memorial Narratives of African Women in Antebellum New England.” Legacy, vol. 20, no.1/2 (2003) 38-46 www.jstor.org/stable/25679448.

8 Ibid

9 Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. The Age of Phillis. Wesleyan Poetry (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2020) 167-187

10 Spear, Chole. Memoir of Mrs. Chloe Spear, a Native of Africa, Who Was Enslaved in Childhood, and Died in Boston, January 3, 1815 ... Aged 65 Years. (Boston: Loring, 1832)

11 Ibid

12 Ibid

13 Cohen, Lara Langer, and Stein, Jordan Alexander. The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture. (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) 101-132

14 Ibid

15 Ibid

16 Ibid

17 Ibid

18 Bennett, Nolan. “To Narrate and Denounce: Frederick Douglass and the Politics of Personal Narrative.” Political Theory, vol. 44, no. 2 (2016) www.jstor.org/stable/24768038. 240-264

19 Ibid

20 Douglass, Frederick. “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2014) 379

21 Bennett, Nolan. “To Narrate and Denounce: Frederick Douglass and the Politics of Personal Narrative.” Political Theory, vol. 44, no. 2 (2016) www.jstor.org/stable/24768038. 240-264

22 Cohen, Lara Langer, and Stein, Jordan Alexander. The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture. (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) 107-126

23 Gates, Henry Louis, Jr.. “Editor's Introduction: Writing ‘Race’ and the Difference It Makes.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 1 (1985) 1-19 www.jstor.org/stable/1343459.

24 Broady, Kristen E., et al. “Passing and the Costs and Benefits of Appropriating Blackness.” The Review of Black Political Economy, vol. 45, no. 2 (2018) 105-119 doi:10.1177/0034644618789182.

Bibliography

Bennett, Nolan. “To Narrate and Denounce: Frederick Douglass and the Politics of Personal Narrative.” Political Theory, vol. 44, no. 2, 2016, www.jstor.org/stable/24768038.

“Bobalition of Slavery.” Boston Massachusetts, 1832. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661751/.

Broady, Kristen E., et al. “Passing and the Costs and Benefits of Appropriating Blackness.” The Review of Black Political Economy, vol. 45, no. 2, 2018, doi:10.1177/0034644618789182.

Brown, Lois. “Memorial Narratives of African Women in Antebellum New England.” Legacy, vol. 20, no. 1/2, 2003, www.jstor.org/stable/25679448.

Browne, Martha Griffith. Autobiography of a Female Slave. Jackson: Banner Books/University Press of Mississippi, 1998. http://archive.org/details/autobiographyoff00brow.

Cohen, Lara Langer, and Stein, Jordan Alexander. Early African American Print Culture. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Cohen, Laura Langer. The Fabrication of American Literature: Fraudulence and Antebellum Print Culture. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Douglass, Frederick. “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Valerie A. Smith, W.W. Norton & Company, 2014, pp. 330-393.

“Dreadful Riot on Negro Hill!” Boston Massachusetts, 1827. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661732/.

“Frederick Douglass.” National Park Service https://www.nps.gov/people/frederick-douglass.htm

Gardner, Eric. “The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book: An Antebellum Text By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005.

Garrison, William Lloyd, and James Brown Yerrinton. "The liberator."January 7, 1832. Digital Commonwealth. Boston, MA: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp. Newspaper.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr.. “Editor's Introduction: Writing ‘Race’ and the Difference It Makes.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 1, 1985, www.jstor.org/stable/1343459.

“Grand bobalition, or ‘Great anniversary fussible.’”. Boston Massachusetts, 1821. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661721/.

Hildreth, Richard. The Slave: Or Memoirs of Archy Moore. Boston, 1836. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/moore1/menu.html.

Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. The Age of Phillis. Wesleyan Poetry. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2020.

Minks, Louisa. “Lucy Terry Prince.” Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield MA. Painting.

“Portrait of James Williams.” Narrative of James Williams, An American Slave … by James Williams, Boston/New York, 1838. Portrait.

Spear, Chloe. Memoir of Mrs. Chloe Spear, a Native of Africa, Who Was Enslaved in Childhood, and Died in Boston, January 3, 1815 ... Aged 65 Years. Boston: James Loring, 1832. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/brownrw/brownrw.html.

Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley.New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.