Chloe Russel, Maria Stewart, and the Cult of True Womanhood

The Cult of True Womanhood (also known as the Cult of Domesticity) dominated the culture of the nineteenth century by detailing the four characteristics of the “ideal”woman. Those characteristics were:

- Religion/Piety

- An ideal woman would be completely devoted to God in order to be a spiritual guide for her children.

- Purity

- An ideal woman would be chaste and pure. Premarital sex was strictly forbidden in the model of the Cult of Domesticity.

- Submissiveness

- An ideal woman respects and obeys her husband.

- Domesticity

- An ideal woman has her place in the private sphere. The private sphere is the household, which a woman should upkeep for her husband. Women were expected to avoid the public sphere, as this was seen as a place for men. A woman appearing in the public sphere was scandalous and improper.

Both Chloe Russel and Maria Stewart engage with ideas of domesticity in their work. Although Russel and Stewart interact with the Cult of True Womanhood in very different ways, both authors empowered women to break away from the restrictiveness of the Cult of Domesticity.

Maria Stewart

Maria Stewart defied the expectations of the Cult of Domesticity from a young age. Stewart was widowed early in life, giving her independence she was not afforded in marriage. As a very religious woman, she fulfilled the Cult of Domesticity pillar of piety, yet Stewart used religion to further arguments regarding abolition and women's rights. Stewart gave lectures in public to range of diverse audiences including men, women, people of color, and white listeners. “Stewart challenged her audience, both it’s black and white members, to greater efforts on behalf of educational and economic opportunity for young black women as well as men in the city of Boston" (181). Inevitably making Stewart a threat to the Cult of Domesticity, as a widowed woman acting in the public sphere, Stewart defied male authority and societal norms in order to further the cause for abolition and women's suffrage.

Chloe Russel

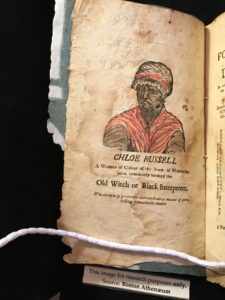

Little is known about Chloe Russell’s background. Scholar Eric Gardner has done extensive research into her possible identity and found evidence of a Chloe Russell living in Boston, however. However, it cannot be fully determined if she is the author or if she was involved in the publication at all (Gardner 264-265). It is possible that this Russell simply licensed her name for publication use or was not involved in the publication at all. Gardner explains the "possibility that ‘Chloe Russel’ was invented by a publisher hoping to capitalize on the stereotype of the African American fortune-teller” (264). It's the Chloe Russell found in the Boston census is the author of this text, then, the author would be a widow, similar to Stewart. Regardless if Chloe Russell was created by a publishing company, The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book is still open to a feminist reading.

“Lecture Delivered at Franklin Hall”

Maria Stewart gave this lecture in September of 1832 to a mixed-race audience of both men and women.

Stewart begins her speech by establishing her authority as a speaker. Stewart sees herself as a messenger of God, giving herself autonomy through religion. In her speech Stewart recollects a conversation between herself and God: “Who shall go forward, and take off the reproach that is cast upon the people of color? Shall it be a woman?’ And my heart made this reply–‘If it is thy will, be it even so, Lord Jesus!’” (Stewart 183). This makes her a powerful figure to bother her readers and her audience, because she was chosen by God for this feminist and abolitionist cause. A woman claiming to be called by God disputed the social order constructed by the Cult of Domesticity, as explained by scholar Pelletier, “In claiming that she was called by God, Stewart unsettles the patriarchal order by contending that God is imbuing a woman with the authority to act on his behalf” (Pelletier 65). Not only is Stewart presenting herself as an authority figure within the movement, she presents herself as a leader. Female involvement was essential to Stewart, "portraying women not only as integral members of the Black resistance movement but also as its leaders" (Henderson 57). This also completely disrupts the social order, as Stewart is a widowed woman rallying other women to manifest their own power.

Stewart argues that women are just as capable as their male counterparts, but are not afforded the same opportunities as men. As argued by Pelletier, Stewart makes “an impassioned plea for the expansion of political liberties that would afford America’s most dispossessed--black women-- the ability to chart their own corse” (61). Without opportunity, Stewart argues, women will never be able to prove themselves. Stewart declares: “And such is the powerful force of prejudice. Let our girls possess what amiable qualities of soul they may; let their characters be fair and spotless as innocence itself; let their natural taste and ingenuity be what they may; it is impossible for scarce an individual of them to rise above the condition of servants” (Stewart 184). Prejudice is a "powerful force," which gains power when women confine themselves to domesticity. Because women are expected to stay in the domestic sphere, they cannot explore their "natural taste and ingenuity" in order to prove the capabilities of women and the ideal of domesticity in the Cult of Domesticity is seen as the root cause for this If women are never afforded the opportunity to prove themselves, they will never be able to escape the domestic sphere. Therefore, it was on the shoulders of women to cause “Fundamental social transformation in the form of institutional creation... the efforts of Black women [are] a primary mechanism through which such institutional creation would be affected” (Carter 69). An upheaval of the cultural norms of the Cult of Domesticity was necessary for the success of women.

Stewart argues that Cult of Domesticity not only prevented women from portraying their full potential , but life in the Cult of True Womanhood was unfulfilling. Stewart states, “And such is the horrible idea that I entertain respecting a life of servitude, that if I conceived of there being no possibility of my rising above the condition of a servant, I would gladly hail death as a welcome messenger” (Stewart 184). The Cult of True Womanhood created an extremely unfulfilling life that does not provide happiness, and for Stewart this is not a life worth living. However, Stewart does make it very clear that this sad existence is not intrinsically linked to womanhood, but rather current social standards. Instead, Stewart, “challenged African-American women to reject the negative images of Black womanhood so prominent in her times, pointing out that race, gender, and class oppression were the fundamental causes of Black women’s poverty” (Collins 3). There was a path to happiness for women, but it involved overturning the Cult of Domesticity, which trapped women in cycles of unhappiness and poverty. Stewart challenges the domestic sphere directly in her speech stating, “look at many of the most worthy and interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen’s kitchens” (Stewart 185). While the Cult of Domesticity saw a woman's place as in a man's kitchen, Stewart saw this as a damnation.

The solution to escape the Cult of Domesticity was education in Stewart's perception. Stewart states in her speech, “O, horrible idea, indeed! to possess noble souls aspiring after high and honorable acquirements, yet confined by the chains of ignorance and poverty to lives of continual drudgery and toil. Neither do I know of any who have enriched themselves by spending their lives as house-domestics, washing windows, shaking carpets, brushing boots, or tending upon gentlemen’s tables” (Stewart 184). Women have "noble souls" aspiring to a greater existence than the one of the domestic sphere, yet they are chained to their trivial domestic duties. Appealing to her male audience Stewart questions “Had we had the opportunity that you have had, to improve our moral and mental faculties, what would have hindered our intellects from being as bright, and our manners from being as dignified as yours?” (Stewart 185). Sexism is an issue of opportunity. Women are just as bright as men, but are not given the education to allow them to expand their minds and prove themselves.

The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book

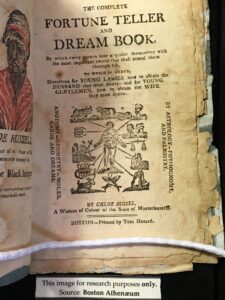

On the cover of Chloe Russell's work, it declares the piece is “By Chloe Russel, A Woman of Colour in the States of Massachusetts.”to include Russell's race and location on the cover of the work certainly had to do with the marketing of the novel. By directly stating that the book is by a woman, it appeals to female empathy and community. Because of the stereotypes associated with Black women having clairvoyant abilities, the decision to include her race catered to both African American and potential white readers, as this stereotype carried with a sense of authority for the book's claims. While the book is marketed towards both genders, it pays more attention to its female audience creating a community among its female readership.

The title page also declares “Directions for young ladies to obtain the HUSBAND they most desire.” In today’s standards it may seem backward to have a book designed to help women gain a husband, yet the sense of choice in marriage was a form of power in the nineteenth century. This book sought to help women get the husband they wanted most, , viewing as a decision in which women have the power to select the man they most desire.

The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book begins with Russel recounting her life. Russel described a history of hardship derived from her enslavement and the loss of several loved ones. Russel lost her husband as a young man and was left to support herself on her own. She discovered that as an escape she can exit this world and enter “the world of spirits, where there was nothing but joy and happiness” (Gardner 271). As an enslaved and as a free woman, Russel relied on the escapism of the world of spirits in order to bring her happiness. Russel did not speak of happiness found in our world, especially not in the domestic sphere. While the feminism in this argument was not direct, it did exist in the subtext.

Russel described being widowed early in life, leaving her with few options to support herself. It was lucrative for Russel to use her clairvoyant abilities to give readings in exchange for payment. Russel became very successful and describes that “With my Money I purchased a small house, and devoted my whole time to interpretation of dreams” (Gardner 272). Not only was Russel a widowed woman in a house she paid for, but she also raised money to free enslaved people (Gardner 273). Russel is a very powerful and influential woman, certainly not abiding by the Cult of True Womanhood. Not only was Russel not solely within the domestic sphere, she was also not submissive to any man. By purchasing her own home, running her own business, and fundraising to free enslaved people, Russel took on a typically masculine roles in the eyes of the Cult of Domesticity, providing her readers with an empowering role model.

In the section “Directions to young ladies how to obtain husbands they most desire” Russell explores how to give women within the domestic sphere autonomy in the decision of marriage. This gives women power within the domestic sphere to make such large decisions.Marriage is typically an institution dominated by men. Men are the ones who propose marriage, taking away the power of choice from women, as they are ultimately beholden to the will of a man.. By providing women with a spell directed at men, Russell gives women the control when it comes to marriage. This breaks away from the submissiveness of the Cult of Domesticity and empowers women from within the domestic sphere to gain more autonomy and power.

The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book also features a section on Palmistry. This selection aims to teach women how to tell someone's true intentions by reading their palms. The directions state “If the hollow palm of one hand… the person will be of a humorsome, uneven and testy temper, jealous and hasty, quarrelsome and fighting, and endeavoring to set others by the eats, he will meet with very frequent misfortunes, and bear them very uneasily” (Gardner 285). Here Russell provides a list of red flags for women, empowering them to make a decision on the type of man they would not want to be with. This section clearly outlines characteristics of men that are undesirable and warns women against marrying such a man. Russell clearly outlines that a person with a bad temper and jealousy is not someone who will bring good fortune. While many may argue that palmistry is not real, it is this speech against the violence of men that is important in this section, rather than the palmistry.

Conclusion

Both Stewart and Russell are interested in how women can escape the private sphere and instead be empowered within the domestic sphere. Stewart highlights that women are capable of doing what a man can but are confined to domesticity and not granted the opportunity to grow in the public sphere. Russell’s ideas of how to empower women are less overt than those of Stewart, but nonetheless challenged the typical model of the cult of domesticity by giving them autonomy in their lives and decisions. Both women, in their argument and their backstories, further this feminist cause by empowering women to challenge the restrictions of the domestic sphere.

Bibliography

Andrews, William L and Foster, Frances Smith. “Maria W. Stewart.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Valerie Smith, 2014, 3rd ed, Vol. 1. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014, pp. 181-182.

Carter, Jacoby Adeshei. “The Insurrectionist Challenge to Pragmatism and Maria W. Stewart's Feminist Insurrectionist Ethics.” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, vol. 49, no. 1, 2013, pp. 54–73. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.49.1.54.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York City, Routledge, 2000.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book’: An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 2, 2005, pp. 259–288. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30045526.

Henderson, Christina. “Sympathetic Violence: Maria Stewart’s Antebellum Vision of African American Resistance.” MELUS, vol. 38, no. 4, 2013, pp. 52-75. Oxford Academics, https://academic-oup com.ezproxy.neu.edu/melus/article/38/4/52/975759#.

Pelletier, Kevin. Apocalyptic Sentimentalism : Love and Fear in U.S. Antebellum Literature, University of Georgia Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1836114.

Stewart, Maria. “Lecture Delivered at Franklin Hall.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Valerie Smith, 2014, 3rd ed, Vol. 1. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014, pp. 182-185.

Web page by Maddie Peebles