Created by Brendy Jerome

Introduction

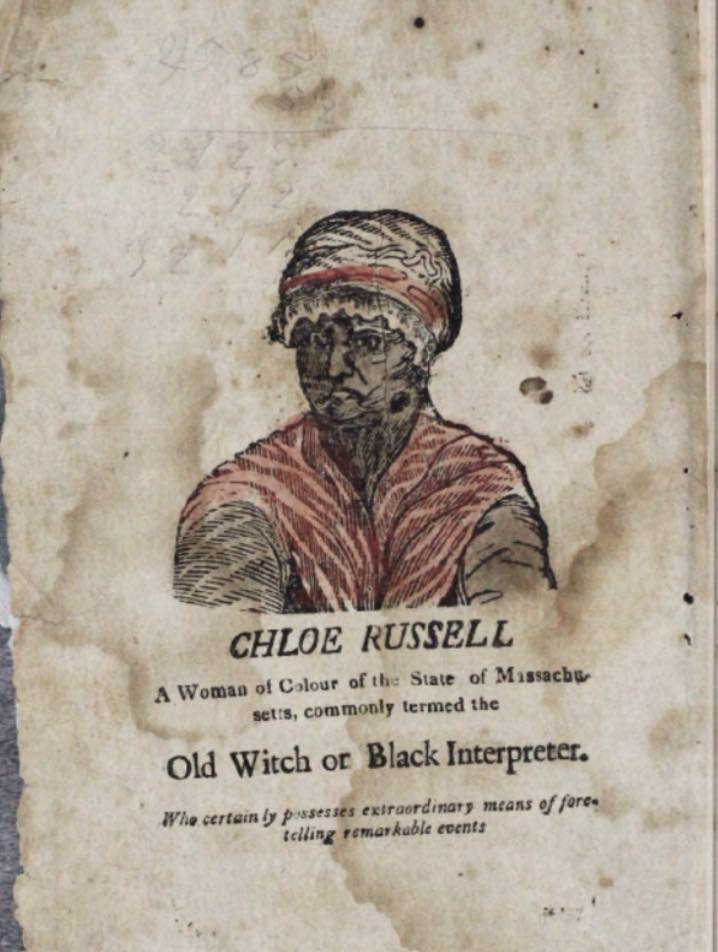

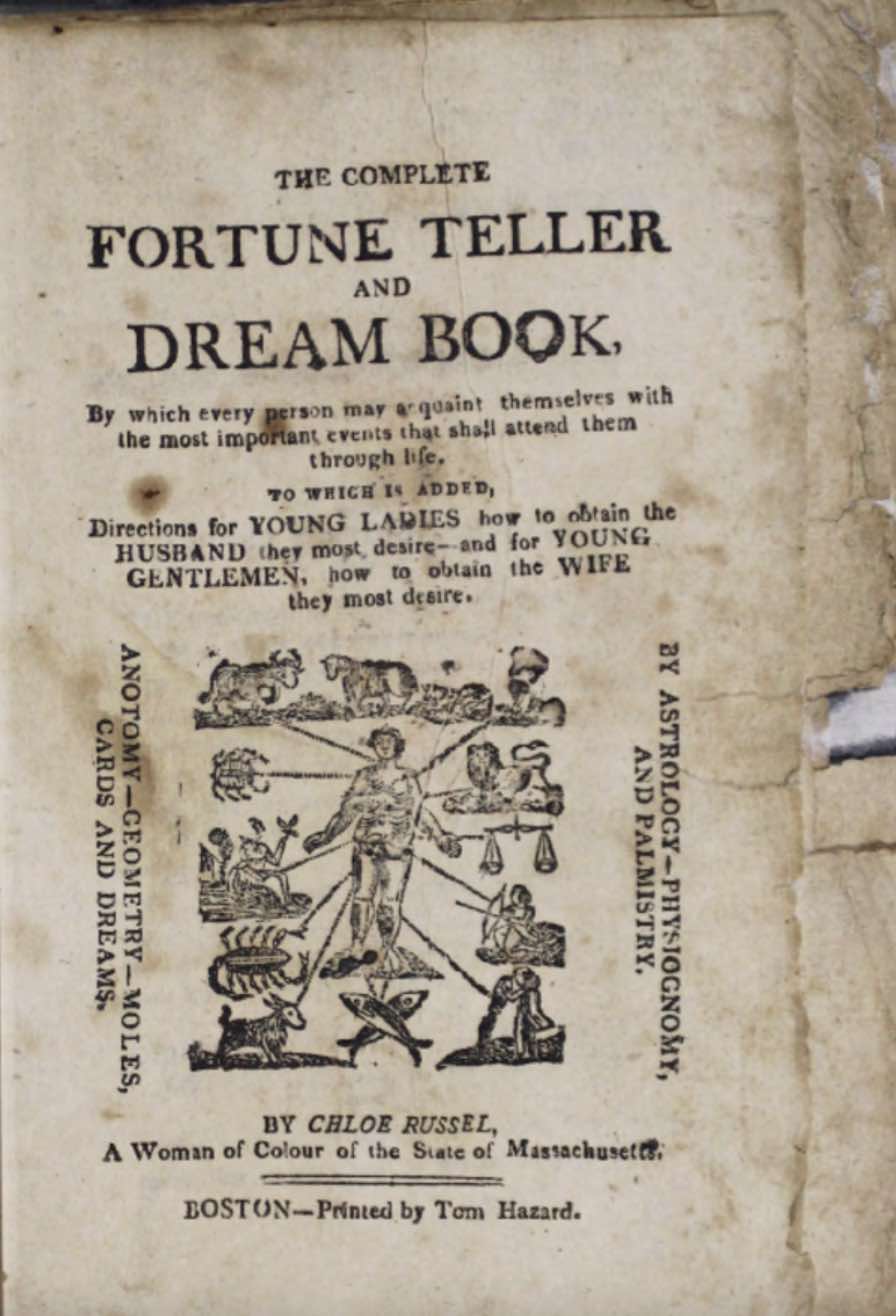

Aside from the obscurity surrounding the identity of the author, it is no coincidence that Chloe Russel[l] is portrayed as a black woman.1 There is significant historical context behind the association of alternative beliefs such as Cunning or Divination in the African Diaspora. Black women especially are often tied to traditional African spirituality according to oral history and written “record”. Additionally, Black women who practice alternative beliefs are often portrayed as “witches” in Western media, contributing to this stereotype. The inclination to characterize African alternative beliefs as sinister and immoral contributes to the racialization of beliefs that don’t align with organized Western religion. As a result, many enslaved African s, such as Chloe Russel, assimilated to Western European culture in order to survive enslavement and life in America.2 However, the publishing of The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book exemplifies the conservation of African culture prior to colonialism, throughout enslavement .

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

General Background on Traditional African Spirituality

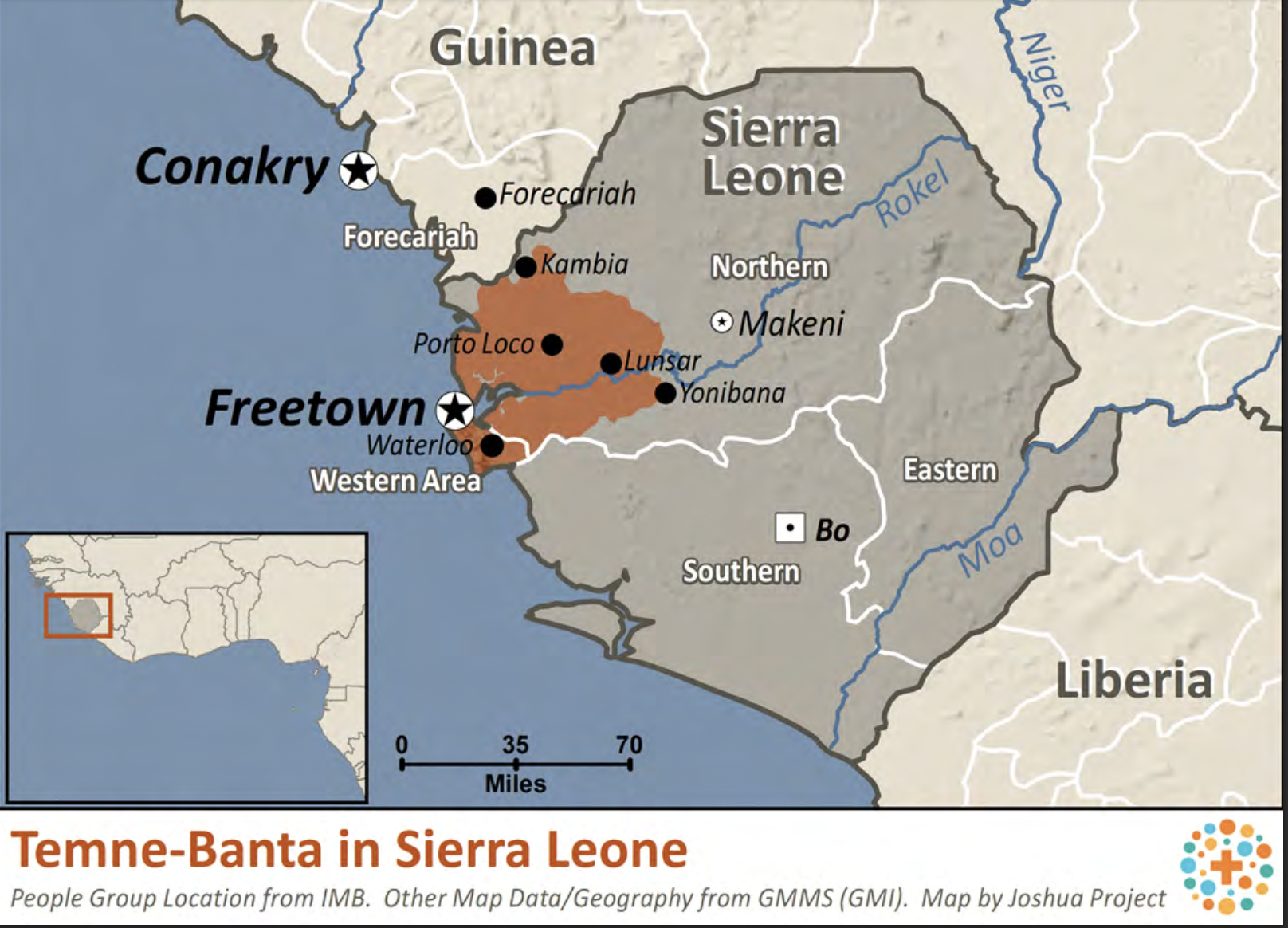

African spirituality is an overarching term used to describe the many different belief systems; primarily passed down to generations orally, in a multitude of cultures in the pre-colonial era. Nonetheless,similar principles are found across traditional civilizations regarding alternative beliefs. In many African civilizations, the universe is explained by the relationships within a trifecta, which include three ideologies the Creator, the Spiritual Realm of ancestors and Divinities, and the Earthly Realm of humans and animals. The trifecta arised in 18-19th century Temne-speaking communities of Sierra Leone, where the narrator claims Chloe Russel was born.3 The Creator is responsible for constructing the universe and life as we know it. For example the creation story believed by the Bakuba people of Zaire (located in Central Africa) entailed that God spewed the sun, the moon, and the stars in addition to a few animals, including human.4 In West African cultures, God can be depicted as an icon, metaphor or symbol.5

Joshua Project, “Temne- Banta in Sierra Leone”

According to traditional African cosmology, the realm of spirits is a principle of order of the universe. The realm of the Creator or Supreme being is distanced from Earth and so the only connection that humans have to their domain is supplied by intermediaries. Intermediaries can be ancestral spirits or those that practice divination to communicate with spirits. Many African peoples believe that everything in the universe has a spirit whether it is alive or not and These entities can be channeled by the offering of shrines, conducting ritualistic dances and/or by reciting special mantras. For example, the Ganda peoples of Uganda (located in East Africa) construct monumental, conical-shaped shrines that are eighty-feet in diameter and two stories high, which are offered as housing to the spirits of royal ancestors.6 There may be hundreds or possibly thousands of intermediaries across the African continent.

Thirdly, humans and other Earthly creatures complete the cyclical composition of life. Contrary to Christianity, in countless forms of African spirituality there is no Heaven or Hell. The cyclical nature of life is emphasized in that every spirit can only be transferred, not destroyed. Humans, including Diveners, are not below the Supreme being, nor above the spiritual realm. Instead there is a reciprocative relationship amongst all beings. The ancestral spirits and Divine beings guide life and nature on Earth in return for offerings and celebration by humans. Diviners can seek guidance from spirit guides using Pa Divination and unveil the truth about the cause of illness in someone else who is afflicted. This ritual is native to those who speak the Chadic language; who lived in present-day Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon and Chad. It is achieved by interpreting the casting of divination pebbles, sacredly endowed by the Creator, in bodies of water.7 Lastly, another important point about the role of humans is their authority over their own fate. The Yoruba peoples believed that humans are in control of their own destiny with the help of intermediaries known as Orishas, to which we are symbolically linked by our heads. Our spirits are not subject to damnation but instead reincarnation can be achieved. Unless we live“unholy” lives, then we are made exempt from the circle of life.8

Arnett, S. William, “Sowo Initiation Helmet Mask of the Sande Society” Sierra Leone, Africa, Mask.

Alternative Practice during the Enslavement Era

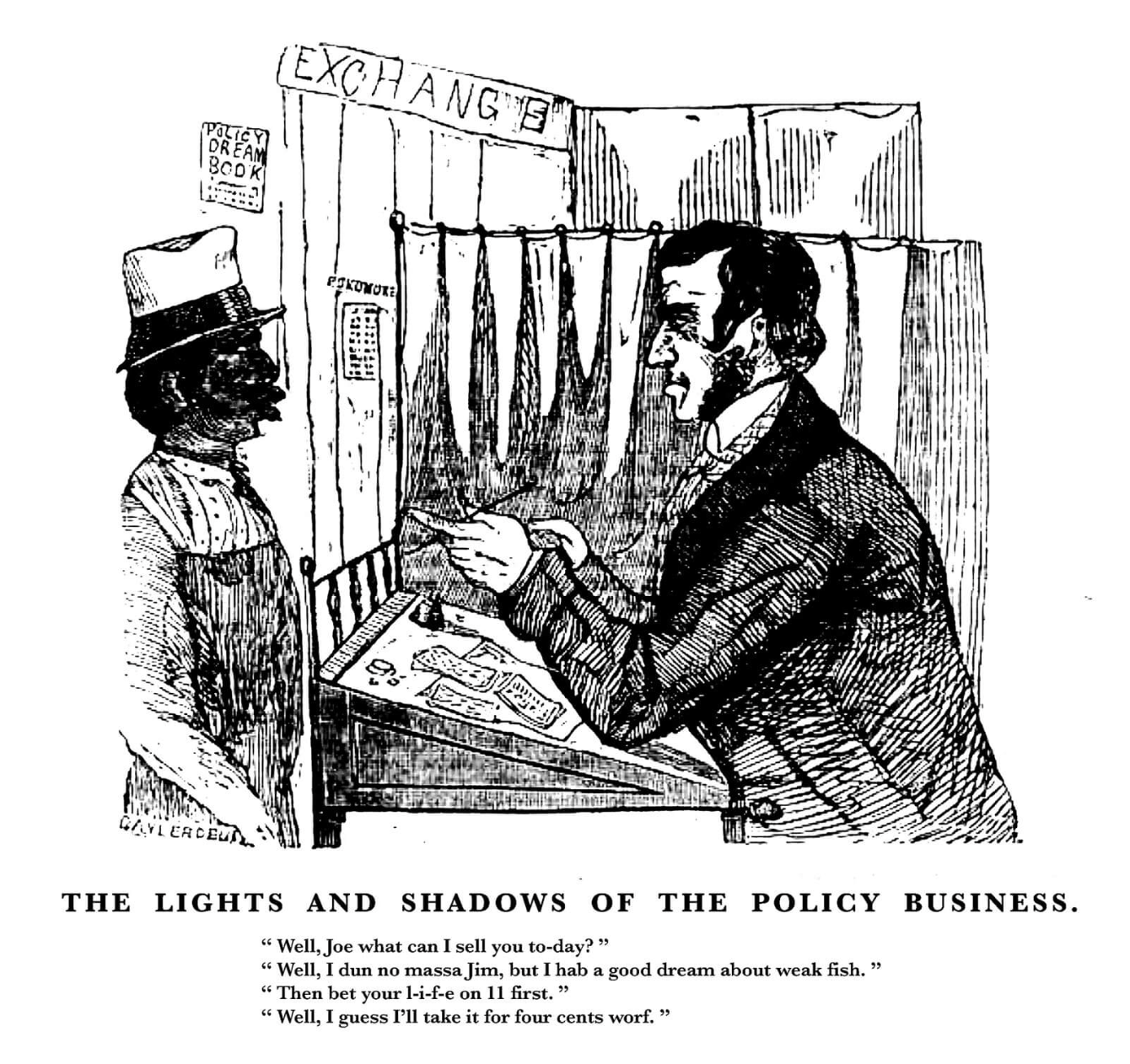

Parallels can be drawn from the products of traditional African spirituality to the alternative practices used by Black people during the enslavement era in the Americas. According to Margarita Guillory Conjure can be defined as the ability to create something out of nothing.9 The Chloe Russel text entails a guide on how to interpret random objects or occurrences in dreams to foretell what will happen in the real future. A related skill known as combinate, is also used by the “Cunning folk” or Black fortune tellers, to connect complex events, people, and objects in dreams to meaningful numbers.10

“Lights and Shadows of the Policy Business,” 1848, National Police Gazette, American Antiquarian Society. Image

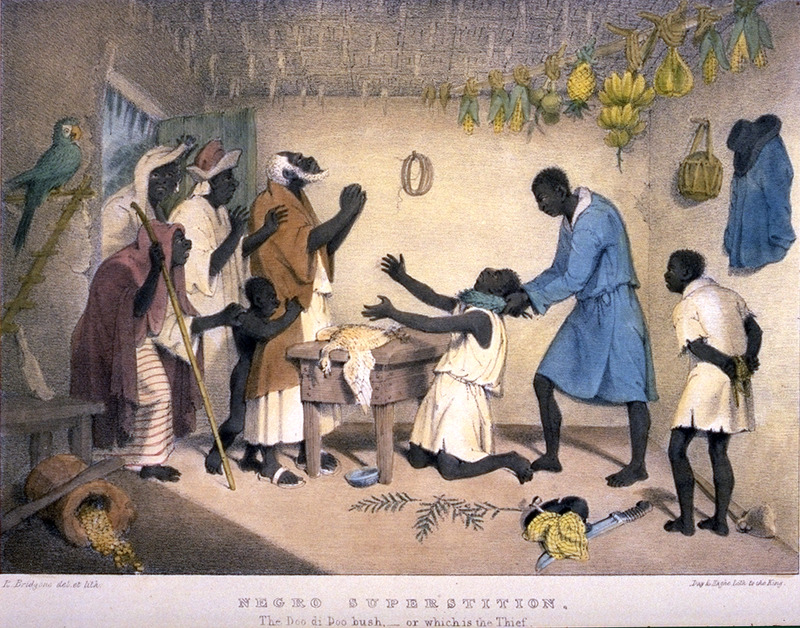

Black enslaved people were said to have used these skills to improve the quality of life for themselves and others under the harsh control of their masters. It was common for there to be at least one rumored Conjurer on American plantations, whom was typically referred to as “Uncle” or “Aunt” in arguably patronizing manners by their white superiors. Primarily though, Conjurers assisted other bonded persons, as shown in Fredrick Douglass’s narrative, where he recounts that a Conjurer named Sandy Jenkins gave him enchanted root to grant him strength before he was tortured by the “slave breaker.”11Akan enslaved people in colonial Jamaica were accused of using Obeah to aid them in a slave uprising known as Tacky's Rebellion. They were believed to have used charms and potions as weapons against their masters, and consequently the practice of Obeah was outlawed in Jamaica.12

Bridgens, Richard, “"An Obeah Practitioner at Work, Trinidad, 1836", West India scenery with illustrations of Negro character, the process of making sugar, &c. from sketches taken during a voyage to, and residence of seven years in, the island of Trinidad, 1836 London, Plate.

In the North, specifically New York, Black people used conjuring and fortune-telling as a source of income. In the early 18th century in Northern cities both the Black and white people became fascinated with Black fortune tellers. The practice of African spirituality was not always readily accepted. The conversion of Conjure into “witchcraft” led to the demonization of African traditional beliefs in Western European culture. This led to oppressive laws restricting the expression of Black people under colonial rule in places like South Africa and the West Indies. The Witchcraft Act of 1735 and Vagrancy Act of 1824 were established to persecute fortune tellers who “threatened the morals of society.” The criminalization of Obeah served to limit the enslaved’s freedom and ability to help one another.13 Similar laws were placed in 19th century Sierra Leone to outlaw “witchcraft.”14

Women and Spirituality

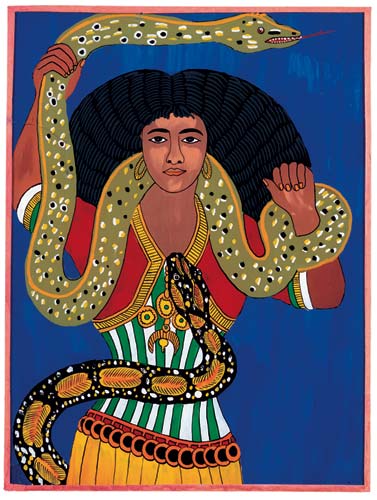

In traditional African Spirituality, women enjoyed more equality compared to societies governed by faiths such as Christianity. They were highly respected and served leadership roles in community rituals. Female goddesses such as Mami Wata from West Africa were also celebrated and believed to be responsible for the continuation of life. The Yoruba peoples claimed that the human body is a container for the spirit. This trend of honoring the wisdom of elders is also seen in the Asante society where only postmenstrual women were allowed to conduct specific healing rituals.15 In Sierra Leone, women were tasked with securing the relationship between humans and deities and/or ancestors. These traditions could account for the speculation around the age of Chloe Russel.16 The narrator claims that she was born in 1745, however evidence from Boston censuses indicates that she was likely to have been born decades later.17

Sane, Zoumana, “Mami Wata,” 1987, Senegal, Glass

Alternative Beliefs in the Media

The contrast between the perception of white European witches and African witches was notable in the 18th/19th centuries. According to Shaw, there was a common notion that European Witches share their divine practices with the public for the betterment of their community, while African witches selfishly keep their plans to themselves.18 The 19th century was in fact the peak of the racialization of witchcraft, in which negative stereotypes, such as cannibalism, evilness, and immorality were imposed on Black practitioners, particularly onto women. Such stereotypes inaccurately characterize the true nature of African spirituality. Granting Black enslaved people the autonomy to practice their own faith ensued a small sense of freedom, which had the propensity to turn into common morale against enslavement. Europeans branded these beliefs as “witchcraft” and Conjurers as “witch doctors” and “hags” that posed a threat to society.19European slave traders also manipulated the image of Conjurors to justify slavery. In colonial Sierra Leone they claimed that witches were to blame for the progression of slavery because they sold their people as part of rituals.20 These characterizations have also manifested in portrayals of alternative practices in the media.

Fredericks, A. “Tituba and the Children,” 1878, Popular History of the United States, vol. 2, Charles Scribner's Sons, 457.

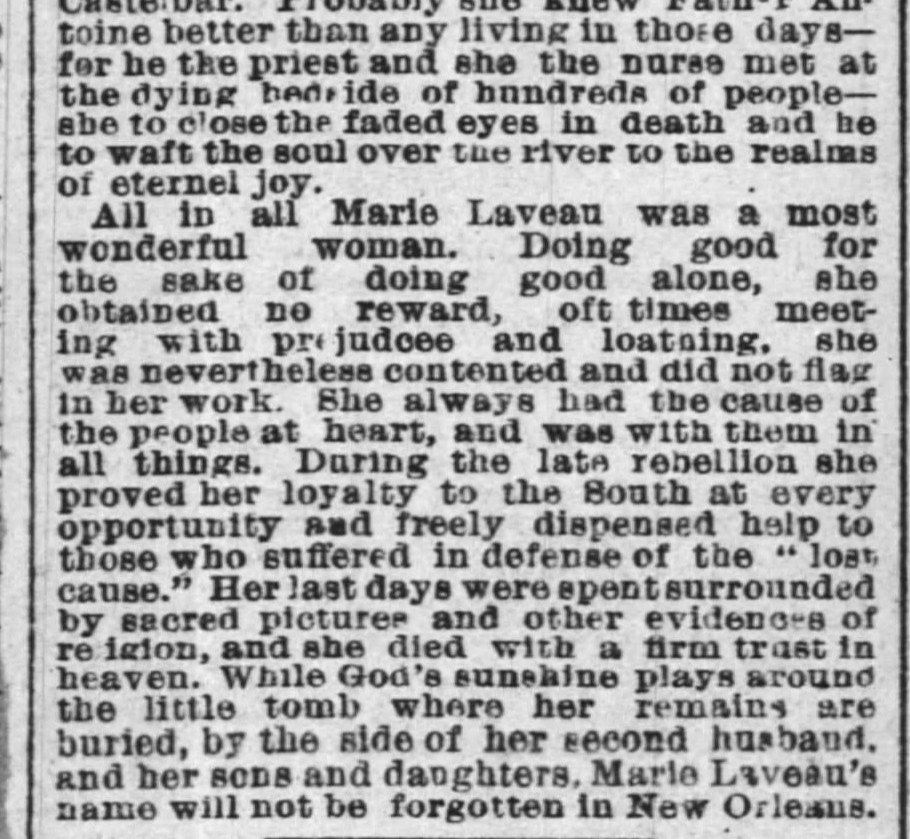

Marie Laveaux,a famous black Conjuror, who attracts curiosity because the mysterious facts of her life were portrayed drastically differently in media versus reality. Laveaux, born in 1801 in New Orleans, Louisiana to free mixed-race parents, grew up as a member of Roman Catholic Church and owned a beauty parlor on Royal Street. Her first marriage to Jacque Paris in 1819 was described as short and miserable. Paris was reported to have disappeared a few years after the couple tied the knot and was declared dead after a year of being missing. Archival evidence suggests she had a child with Paris named Marie Vangelie. The young girl died around the same time her father went missing. She remarried years later to a white man named Jean Lois Christophe Duminy de Glapion to whom she was happily married and thus had 5 documented children. In her elderly years, Laveaux was a charitable person who visited prisoners, and aided the sick as hospitals. She gave up her rights to “Voodoo Queen” in New Orleans on March 21, 1869 and then passed away on June 15, 1881, of natural causes. Her eulogy paints her as an influential and celebrated person in New Orleans.21

Despite the factual evidence of her life, there are many negative rumors and criticisms of Lavaux’s humanity. She was rumored to have murdered her first husband and hide biological children It was also speculated that she had access to tetrodotoxin, colloquially known as “Zombi Poison,” a neurotoxin that slows metabolism and heartbeat to make someone appear to be dead. Supposedly she gave Zombi Poison to prisoners on death row so they were perceived as dead when guards checked on them. A few hours after they were buried Laveaux would then send someone to dig them out.22She was also crucified in news articles at that time for the “blasphemy” of combining Conjure with Roman Catholic. As well as being labeled as an evil witch she was also oversexualized in many rumors, speaking to the hyper-sexualization of black women.

Connecting it Back to Chloe Russel[l]

Although the authorship of the text still remains to be identified, Russel’s portrayal as a black woman provides insight into the historical and contemporary contextualization of African spirituality and its receival by Black and white communities.. There are countess similarities amongst spiritual beliefs in traditional African cultures that support the manufactured African heritage of Chloe Russel.23 Her gender identity and documented age within the text also holds true to the belief that elderly women were more spiritually attuned than men. The sensalization and or controversy surrounding black female Conjurors in society may also provide insight for the intention behind publishing the book, and its subsequent success amongst a variety of audiences.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

Endnotes

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 259-288

- Boaz, Danielle "Fraud, Vagrancy and the Pretended Exercise of Supernatural Powers in England, South Africa and Jamaica" (Law & history, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018) 54-84.

- Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” (American Ethnologist, vol. 24, no. 4, 1997) 856–876

- Olûpọna, Jacob Kehinde. African Spirituality: Forms, Meanings, and Expressions (The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2011)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Guillory, Margarita, and Maria DeBlassie “066 African Diaspora Conjuring Practices in Popular Culture” (Shelf Love)

- White, Shane “The Gold Diggers of 1833: African American Dreams, Fortune-Telling, Treasure-Seeking, and Policy in Antebellum New York City” (Journal of Social History, vol. 47, no. 3, 2014) pp. 673–695

- Chireau, Yvonne P Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition, (University of California Press, 2003)

- Boaz, Danielle "Fraud, Vagrancy and the Pretended Exercise of Supernatural Powers in England, South Africa and Jamaica" (Law & history, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018) 54-84.

- Ibid

- Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” (American Ethnologist, vol. 24, no. 4, 1997) 856–876

- Olûpọna, Jacob Kehinde. African Spirituality: Forms, Meanings, and Expressions (The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2011)

- Boaz, Danielle "Fraud, Vagrancy and the Pretended Exercise of Supernatural Powers in England, South Africa and Jamaica" (Law & history, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018) 54-84.

- Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 264 - 265

- Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” (American Ethnologist, vol. 24, no. 4, 1997) 856–876

- Guillory, Margarita, and Maria DeBlassie “066 African Diaspora Conjuring Practices in Popular Culture” (Shelf Love)

- Katrina Keefer “Poro, witchcraft and red water in early colonial Sierra Leone: G. R. Nylander’s ethnography and systems of authority on the Bullom Shore” (Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines, 2020)

- Fandrich, Ina J.. The Mysterious Voodoo Queen, Marie Laveaux : A Study of Powerful Female Leadership in Nineteenth Century New Orleans, (Taylor & Francis Group, 2005)

- Ibid

- Boaz, Danielle "Fraud, Vagrancy and the Pretended Exercise of Supernatural Powers in England, South Africa and Jamaica" (Law & history, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018) 54-84.

Bibliography

Arnett, William. “Sowo Initiation Helmet Mask of the Sande Society” Sierra Leone, Africa, Mask. https://collections.carlos.emory.edu/objects/17909/sowo-initiation-helmet-mask-of-the-sande-society

Boaz, Danielle. "Fraud, Vagrancy and the Pretended Exercise of Supernatural Powers in England, South Africa and Jamaica," 54-84. law&history, 5, no. 1, 2018. https://heinonline-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/lwanhist5&i=63.

Bridgens, Richard. An Obeah Practitioner at Work, Trinidad, 1836", West India scenery : with illustrations of Negro character, the process of making sugar, &c. from sketches taken during a voyage to, and residence of seven years in, the island of Trinidad. London, 1836. Plate.

Chireau, Yvonne P.. Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition, University of California Press, 2003. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=223936.

“Death of Marie Laveau.” The Times-Picayune. New Orleans Louisiana, 17 Jun 1881, Newspaper. https://www.newspapers.com/paper/the-times-picayune/824/

Fandrich, Ina J.. The Mysterious Voodoo Queen, Marie Laveaux : A Study of Powerful Female Leadership in Nineteenth Century New Orleans, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4523411.

Fredericks, A. “Titiba and the Children,” 1878. Popular History of the United States, v 2. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, 457.

Gardner, Eric. ""The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book": An Antebellum Text "By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour,” 259-88. The New England Quarterly 78.2, 2005.

Guillory, Margarita, and Maria DeBlassie. “066. African Diaspora Conjuring Practices in Popular Culture.” Shelf Lovecom/episodes/season-2/episode-66/066-african-diaspora-conjuring-practices-in-popular-culture/.

Joshua Project. “Temne- Banta in Sierra Leone”https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/10660/SL

Katrina Keefer “Poro, witchcraft and red water in early colonial Sierra Leone: G. R. Nylander’s ethnography and systems of authority on the Bullom Shore” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines, 2020 DOI: 1080/00083968.2020.1723658

“Lights and Shadows of the Policy Business.” National Police Gazette, July 1 1848. American Antiquarian Society. Image

Olûpọna, Jacob Kehinde. African Spirituality: Forms, Meanings, and Expressions. The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2011.

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book

Sane, Zoumana. “Mami Wata.” Senegal, 1987. Glass https://africa.si.edu/exhibits/mamiwata/intro.html

Shaw, Rosalind. “The Production of Witchcraft/Witchcraft as Production: Memory, Modernity, and the Slave Trade in Sierra Leone.” American Ethnologist, 856–87. Vol. 24, no. 4, 1997. jstor.org/stable/646812.

Tagwirei, Cuthbeth. "The "Horror" of African Spirituality." Research in African Literatures, 22-36. 48.2 2017. 22-36.

West, Elizabeth J.. African Spirituality in Black Women’s Fiction: Threaded Visions of Memory, Community, Nature and Being, Lexington Books, 2011. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=860124. Nature and Being (Lexington Books, 2011)

White, Shane. “The Gold Diggers of 1833: African American Dreams, Fortune-Telling, Treasure-Seeking, and Policy in Antebellum New York City.” Journal of Social History, vol. 47, no. 3, 2014, pp. 673–695. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43305955.