Created by Maura Intemann and Savita Maharaj

Introduction

In the late 17th century, Puritan superstitions around witchcraft, mystic abilities, and the devil led to the imprisonment and execution of numerous “accused” witches in New England. By the early 1800s, the once-taboo topic of witchcraft had become romanticized fiction and commodified in the fortune-telling books. In order to understand the socio-historical context that Chloe Russell’s The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book was published—and to possibly uncover the mystery of the book’s authorship—it’s important to map out that drastic change in popular opinion about witchcraft, as well as other cultural shifts of the time.

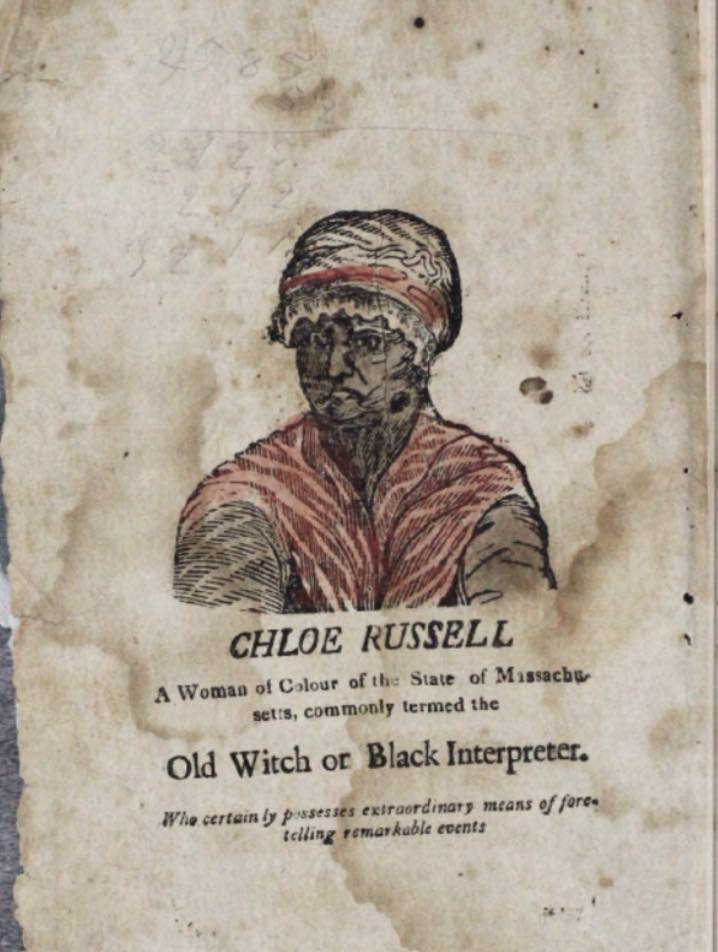

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. Book.

Salem’s Tituba and Other Representations of Witches

According to Eric Gardner, there was a real African American woman named Chloe Russell living in Boston in the early 19th century, when The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book was published. Yet questions remain as to whether the book was truly penned by her, or if it was the creation of a white publisher borrowing content from other fortune telling books at the time.1 Russell is described in the byline as “A Woman of Color, living in the State of Massachusetts, commonly termed the Old Witch or Black Interpreter.” One can’t help but to think of another woman of color who looms large in Massachusetts witchcraft lore—Tituba, a self-professed witch who was one of the first to be accused during the Salem Witch Trials.

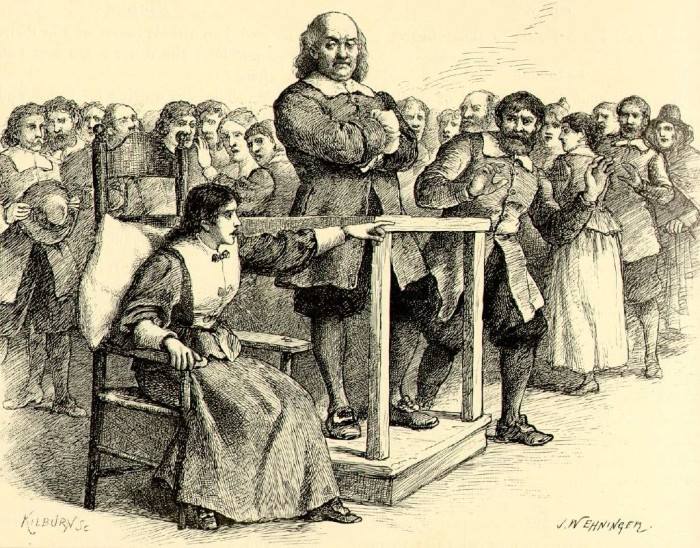

Ehninger, John W, "Giles Corey of Salem Farms," The Poetical Works of Longfellow, 1880, p. 723.

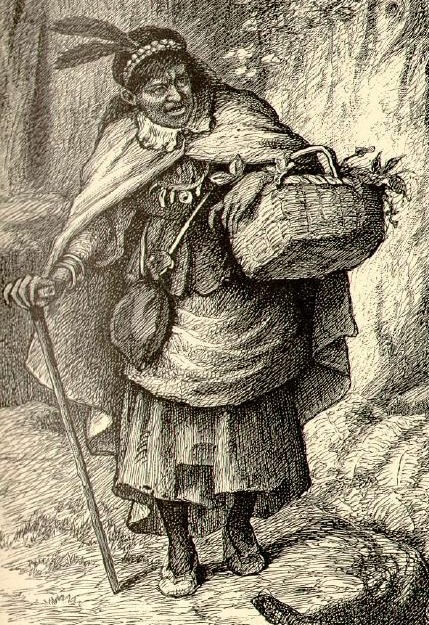

Although we can’t know what Tituba truly looked like, she was often described in fiction as an outsider, someone who white people avoided “because she embodied their racialized religious fear.”2 The Puritans of Salem saw Tituba as a representative of Satan – more diabolical a presence than the accused white witches of the community.3 This racial fear underpins the way she is represented in the actual trial records from 1692. In court documents, Tituba is racialized both as Native American and Black. Accusers who testified against Tituba first refer to her as African, and later as Indian—these same witnesses describe the Devil in a similar way, first as Black and later as “tawny,” or Indian.4 18th and 19th century European Americans consistently associated the Devil with a figure racalized as non-white, speaking to their belief that African Americans were uniquely gifted or suited to the practice of witchcraft.5 Witchcraft practices via certain African spiritual and religious traditions did persist throughout New England among African Americans.6 The perception that Black Americans were particularly knowledgeable about witchcraft continued through the 19th century, shown through different representations of witches in fiction.

Fredericks, A. “Tituba and the Children,” 1878, Popular History of the United States, vol. 2, Charles Scribner's Sons, 457.

Many fictional witches were depicted as white and were often described as “ancient,” and “sharp-tongued,” like John Greenleaf Whittier’s Alice Knight of The Haunted House.7Others were “old crones,” and “ugly,” “old grannies.”8 But in Hope Leslie, one of the more commercially successful and significant works of 19th century witchcraft fiction, C.M. Sedgewick describes “an old Indian Hag” who was sentenced to death for “hellish incantations.”9 Sedgewick’s construction of an “Indian” witch seems to point towards those lasting popular conceptions of Tituba, the original witch of Massachusetts.

“John Greenleaf Whittier” NPS.

In Chloe Russell’s The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book, an image of Russell appears before the title page, above the labels “Old Witch, or Black Interpreter.” She’s scowling, with wrinkled, dark skin, and moles in locations that—according to her own fortune-telling advice—indicate prosperity. These physical identifiers seem to appeal to the popular representations of old, white witches, while also speaking to the belief that people of color had a particular insight into witchcraft. These labels and the visual representation of Russell assert her authority as a fortune-teller by capturing all those images and archetypes within the pop-cultural landscape at the time.

Mapping the Change: The War of 1812 and the Witchcraft Fiction Boom

Where Tituba’s confession of witchcraft led to her imprisonment, Chloe Russell’s claim to “great powers” and self-characterization as an “old witch” added to her narrative power and led to her selling books. What allowed for this change in popular perception of witchcraft, and what caused this topic to be revitalized in literature and popular culture?

Cranstone, Lefevre James. "Giles Corey of Salem Farms," 1880, The Poetical Works of Longfellow, Houghton Mifflin Boston, 752.

Scholars look to the early 1800s as a time of great change in American culture and society. America was a new nation, still striving to assert itself as independent. Just a few decades after winning the revolution, America and Britain clashed again in the War of 1812. Though the results of this war were somewhat ambiguous, the United States emerged with a few major victories and gained a newfound sense of national pride. What was certain was that America had proven itself as a major player on the global stage. This post-war period was marked by renewed optimism and patriotism. The early 1800s began a renaissance of literature—writers were beginning to articulate what exactly an American Literature could look like. Some writers found inspiration in periods of what they now embraced as distinctly American history, periods that were “ready for the novelist’s purpose.”10 This embracing of history through fiction was a strong way to articulate post-war national pride. As historian G. Harrison Orians writes, the colonial period was of a particular interest to writers:

“Fertilest of these were the colonial days of New England, and so optimistic [were] the romantic possibilities of this period that in the decade following...many phases of Puritan life were poured into fiction. Witchcraft, as one of the colorful though minor incidents of that life, was soon appropriated.”11

The sudden boom of witchcraft fiction in the early 1800s illustrated this patriotic interest and represented an effort to solidify an American national identity after the War of 1812. The rise of fortune-telling books in the 1820s represents this same identity-building effort, but also fits into the American literary tradition concerned with “ideas of destiny, promise, rhetorical prophecy, the realization of millennial visions in future time.”12 Furthermore, fortune-telling books represented a kind of literary resistance by those left at the margins of this supposedly great, new American society—within which the institution of slavery was still deeply entrenched. Supernatural methods of predicting and controlling the future, such as those outlined by Chloe Russell, could be taken by other marginalized folks as methods of gaining control over situations not controllable “by more direct physical means.”13

Minstrelsy and the Question of Authorship

As Eric Gardner writes, there still remains a question of whether The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book was written by a Black woman named Chloe Russell or whether the character was created by a white publisher “hoping to capitalize on the stereotype of the African American fortune-teller,” or on “the belief that ‘cunning persons’...were of African and/or Native American ancestry.”14 If the book was actually written or compiled by white publisher Abel Brown of New Hampshire,15 then it’s important to note another major cultural insurgence of the post War of 1812 period: minstrelsy.

Hawkins, Mical, and William Clifton. “Back side Albany, a Comic Ballad,” 1837, Thomas Birch, New York, monographic. Notated Music.

David Waldstreicher writes about minstrelsy’s war-time origins, noting the war’s context of “black sailors and emerging black political and literary culture in the North.”16 Waldstreicher situated minstrelsy as part of the patriotism and “reinvention of American nationhood,” sparked by the war.17 The first blackface minstrel song, “Back-side Albany,” debuted a few weeks after the American victory at the Battle of Plattsburgh, as part of a play about that campaign. According to 19th century writer Benson J. Lossing, it was one of the most popular songs written during the war. While writers of witchcraft fiction romanticized the colonial period, white minstrel performers in blackface asserted their own national identity through the “ventriloquizing” of African Americans.18 Minstrel performers’ derisive racialization constructed an American identity defined by exclusion, and by the maintenance of a racial hierarchy many white Americans already felt slipping away.

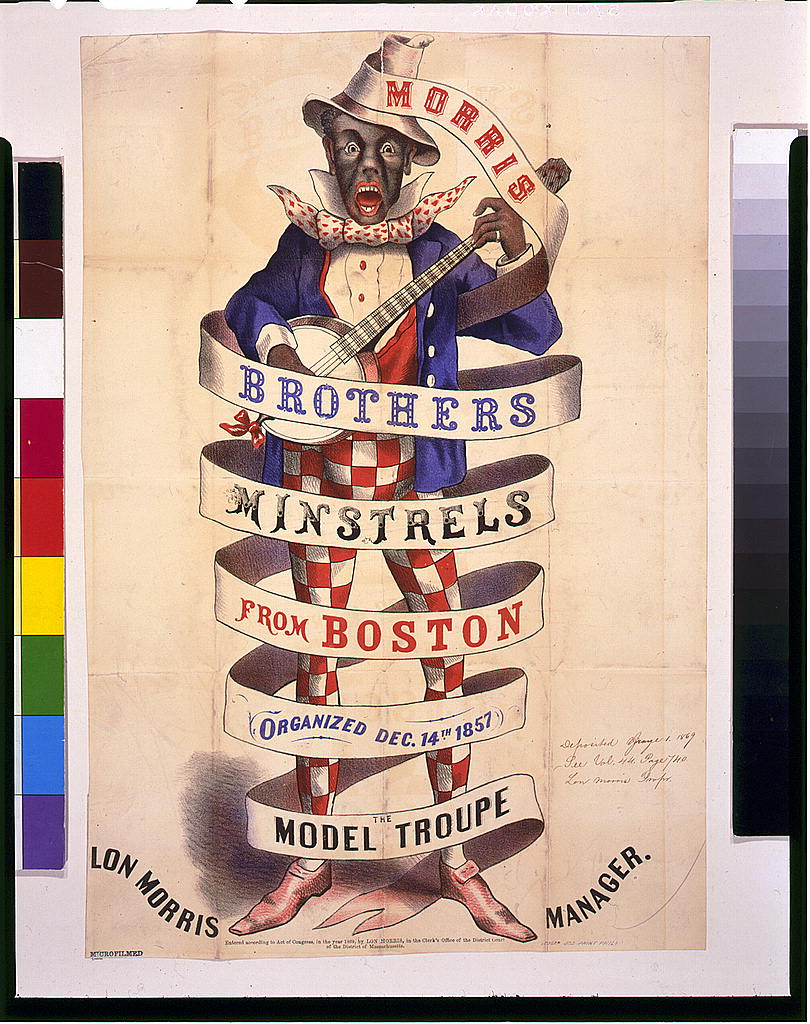

Ledger Job Printing Office, “Morris Brothers minstrels from Boston, organized Dec. 14th, --The model troupe / Ledger Job Print,” ca. 1869, Phila. Boston Massachusetts, Photograph.

If Chloe Russell’s The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book was really a creation of Abel Brown, a white publisher appropriating content from other fortune-telling books, he could have certainly been capitalizing on this major post-war current of popular culture by actually performing a kind of minstrelsy in print. Not only would Brown have stolen content from other fortune-telling books, but he would also have fabricated the narrative of Chloe Russell’s life that appears at the beginning of the book, reproduces some of the emerging tropes of early slave and spiritual narratives like that of Olaudah Equiano.19 Just as minstrelsy began as a representation of white backlash to African American participation in the War of 1812, Brown’s construction of the Chloe Russell character contributed to the Black and Native American witch stereotype, originated by the figure of Tituba, and also as retaliation to the growing popularity of early Black writers.

Endnotes

1 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 259-288

2 Tucker, Veta Smith. “Purloined Identity: The Racial Metamorphosis of Tituba of Salem Village.” (Grand Valley State University)

3 Ibid

4 McMillan, Timothy J. “Black Magic: Witchcraft, Race, and Resistance in Colonial New England.” Journal of Black Studies, (vol. 25, no. 1, 1994), 99–117. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2784416.

5 Horton, James Oliver. "Culture, Race, and Class in the Colonial North." In Hope of Liberty. (1997)

6 Ibid

7 Orians, G. Harrison. “New England Witchcraft in Fiction.” American Literature, (vol. 2, no. 1, 1930), pp. 54–71. www.jstor.org/stable/2919930.

8 Ibid

9 Ibid

10 Ibid

11 Ibid

12 Giles, Paul. “‘Transnationalism and Classic American Literature.’” Transatlantic Literary Studies: A Reader, edited by Susan Manning and Andrew Taylor, (Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 44–52.

13 McMillan, Timothy J. “Black Magic: Witchcraft, Race, and Resistance in Colonial New England.” Journal of Black Studies, (vol. 25, no. 1, 1994) pp. 99–117. www.jstor.org/stable/2784416.

14 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 259-288

15 Ibid

16 Waldstreicher, David. “Minstrelization and Nationhood: ‘Backside Albany,’ Backlash, and the Wartime Origins of Blackface Minstrelsy.” Warring for America: Cultural Contests in the Era of 1812, edited by Nicole Eustace and Fredrika J. Teute, (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 29–55. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469631769_eustace.6.

17 Ibid

18 Ibid

19 Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” (The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, 2005), 259-288.

Bibliography

Cranstone, Lefevre James. "Giles Corey of Salem Farms," The Poetical Works of Longfellow. Houghton Mifflin Boston, 1880, 752. https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/people/gcoreypics.html

Ehninger, John W. "Giles Corey of Salem Farms," 1880. The Poetical Works of Longfellow. Houghton Mifflin Boston, 1880, p. 723.

Fredericks, A. “Titiba and the Children,” 1878. Popular History of the United States, vol. 2. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, 457.

Gardner, Eric. “‘The Complete Fortune Teller and Dream Book:’ An Antebellum Text ‘By Chloe Russel, a Woman of Colour.’” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2, Jun. 2005, 259-288,

Giles, Paul. “‘‘Transnationalism and Classic American Literature.’” Transatlantic Literary Studies: A Reader, edited by Susan Manning and Andrew Taylor, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2007, pp. 44–52. www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctvxcrwt2

Hawkins, Mical, and William Clifton. “Back side Albany, a Comic Ballad.” Thomas Birch, New York, monographic, 1837. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/sm1837.361610/.

Horton, James Oliver. "Culture, Race, and Class in the Colonial North." In Hope of Liberty. 1997

John Greenleaf Whittier” NPS, https://www.nps.gov/people/john-greenleaf-whittier.htm

Ledger Job Printing Office.“Morris Brothers minstrels from Boston, organized Dec. 14th, --The model troupe / Ledger Job Print,” Boston Massachusetts, ca. 1869. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/96507543/.

McMillan, Timothy J. “Black Magic: Witchcraft, Race, and Resistance in Colonial New England.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, 1994, pp. 99–117. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2784416

Orians, G. Harrison. “New England Witchcraft in Fiction.” American Literature, vol. 2, no. 1, 1930, pp. 54–71. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2919930

Russell, Chloe, The Complete Fortune Teller, and Dream Book, 1824, Boston Athenaeum. 1824, Book.

Tucker, Veta Smith. “Purloined Identity: The Racial Metamorphosis of Tituba of Salem Village.” Grand Valley State University.

Waldstreicher, David. “Minstrelization and Nationhood: ‘Backside Albany,’ Backlash, and the Wartime Origins of Blackface Minstrelsy.” Warring for America: Cultural Contests in the Era of 1812, edited by Nicole Eustace and Fredrika J. Teute, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2017, pp. 29–55. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469631769_eustace.6